I started reading two intellectual history monographs this week that both begin with fascinating glimpses into the germinal moment in which the author ‘found’ their topic. In both cases, it is in an encounter with a large, jumbled but thematically-related heap of books that ignites a question, the question that drives the project. For both experiences are confrontations with books that seemed to have expired, books that are hors d’usage

I started reading two intellectual history monographs this week that both begin with fascinating glimpses into the germinal moment in which the author ‘found’ their topic. In both cases, it is in an encounter with a large, jumbled but thematically-related heap of books that ignites a question, the question that drives the project. For both experiences are confrontations with books that seemed to have expired, books that are hors d’usage

.

“This project began with books. Quite literally,” Leslie Butler writes on the first page of Critical Americans: Victorian Intellectuals and Transatlantic Liberal Reform.

On a trip to New York City early in my graduate career, I browsed through shelves of deaccessioned books outside Columbia University’s Butler Library. Dusty volumes in shades of navy, maroon, and dark green stretched on for yards: twenty-five cents a book, five for a dollar. I had only recently decided to study American history and was intrigued by the multiple volumes filled with the writings of people whose names were only faintly recognizable: the life and letters of Charles Eliot Norton, the complete prose writings and poetical works of James Russell Lowell, the orations and addresses of George William Curtis, the essay collections of Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Twenty dollars poorer and the car weighed down by an impressive new library of nineteenth-century Americana, I headed back to New Haven and began reading. (xi)

In his preface to The Age of the Crisis of Man: Thought and Fiction in America, 1933-1973, Mark Greif evokes a book of a certain bent, also discovered unintentionally, and discovered not singly but in an undignified glob of cheap oblivion:

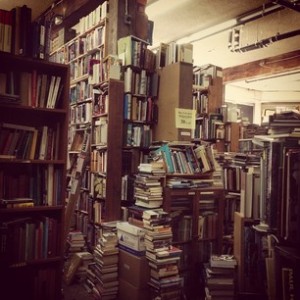

These publications left behind the old campaigners that one still finds, bent-spined, on used bookstore shelves, their back covers decorated with appraisals—of the loss of “the dignity of man,” of man’s fallen “condition,” of the need to save man from himself—embalmed in a language that seems incomprehensible. They are the books, too, that were on the basement shelves of my childhood, in twenty-five-cent or fifty-cent reprints, the worthy and earnest paperbacks that my parents’ generation inherited to educate themselves for the responsibilities of their era. (x)

What these stories are, of course, is the scholar’s assembly of an archive. Particularly in intellectual history—or literary history, a field which both these books gracefully encompass and enlarge—the need to stack books in order to structure a project is universal, and these serendipitous discoveries offer a collection that, in its acutely recalled tangibility—the scuffed spines of Greif’s miscellaneous paperbacks, the deep colors of the cloth backing on Butler’s matched sets—appears natural, delimited, and whole, integral, like the stalactites in an undisturbed cave.

A warm, pleasant cave—more of a den, really—for what suffuses both passages is a feeling of fond familiarity and coziness: these are future friends one encounters, the books that furnish not just a room but the first steps of a career.

But what overwhelms both passages is a sense that these books are historical rejects, the detritus of lost moments in the cultural life of a fading people. Reinforcing this sense of obsolescence is the invocation of prices: although Greif quotes the price his books originally sold at when first published and Butler the price she paid to rescue them from a fate far worse than remaindering, the cheapness of both is foregrounded to give us a crude market value in the academic bazaar. Perhaps it is just that both books explicitly position themselves as recovery projects—no one writes about finding their dissertation topic in a used bookstore’s collection of William James’s works—but the description of these moments places the rescuing of particular physical books and the rehabilitation of a particular intellectual history in perfect parallel.

I do not know that I will write about it in the actual space of my dissertation, but like many of you, I imagine, my archive of printed texts also has a story. But it is a story not of serendipity but of reaping the whirlwind—a process of reassembling the miscellaneous libraries of small universities and even high school that budget cuts and age have scattered into the thousand corners of online bookstalls. Countless books that have gone into my dissertation bear the stamps of school libraries, the inside back covers still holding, in some cases, the check-out cards with the inky smudges of dates contemporaneous with the history I am writing. I am reminded whenever I hold one of these books of Fred Beuttler’s beautiful post on this blog from early last year about his experience overseeing one of these cullings, one of these bibliographic Hunger Games.

Partly, I have pursued this method of acquiring my archive out of necessity—or really, out of convenience: it is simpler to buy a book for a penny-and-shipping than to ILL it and worry about missing the due date. But it is also, in some ways, a hedge against the future. Although it was turned back, the New York Public Library’s rightly derided plan to export an enormous portion of its rich holdings to some heavenforsaken warehouse in godforsaken New Jersey hints at a day when even the most august institutions may rely on HathiTrust or Google Books to supply the needs of scholars hoping to make the kind of find that Greif and Butler made.

Of course, Butler herself relied on a purge from one of these august institutions to jump-start her project, and it was not in the upper stacks of Sterling that Greif located his hoard. The research library, so good for so many things, may simply not be the place for the kind of serendipity that blessed Butler and Greif. Perhaps one needs the aleatory curation of the personal library or the used bookstore for that; one needs to find a space where books do not circulate but rather wind up after hard use.

0