For this week’s post I thought to acquaint you with one of the most entertaining figures of the early US that I’ve come across in my research.

Joseph Dennie was born in Boston in 1768. After attending Harvard, he made a name for himself during the 1790s as an essayist and the editor of a country newspaper, The Farmer’s Weekly Museum, which under his guidance became one of the prominent Federalist papers of the late 1790s. His essays became very popular with the growing rank of men of letters in the early republic, who viewed him as an American Addison.[1] Later, in 1800 he moved from Walpole, New Hampshire to Philadelphia and published the first literary magazine in the US, The Port Folio. During these years Dennie quickly emerged as a star of the fledgling American literary scene and was known as an ostentatious and witty conservative iconoclast, who never shirked from making provocative aristocratic statements in the increasingly democratic atmosphere of the day. Indeed, for many arch-federalists Dennie’s unabashed anglophile and aristocratic flavor constituted a bastion of genteel sensibilities at a time when, in their mind, vulgar popular culture seemed to consume American society.

Joseph Dennie was born in Boston in 1768. After attending Harvard, he made a name for himself during the 1790s as an essayist and the editor of a country newspaper, The Farmer’s Weekly Museum, which under his guidance became one of the prominent Federalist papers of the late 1790s. His essays became very popular with the growing rank of men of letters in the early republic, who viewed him as an American Addison.[1] Later, in 1800 he moved from Walpole, New Hampshire to Philadelphia and published the first literary magazine in the US, The Port Folio. During these years Dennie quickly emerged as a star of the fledgling American literary scene and was known as an ostentatious and witty conservative iconoclast, who never shirked from making provocative aristocratic statements in the increasingly democratic atmosphere of the day. Indeed, for many arch-federalists Dennie’s unabashed anglophile and aristocratic flavor constituted a bastion of genteel sensibilities at a time when, in their mind, vulgar popular culture seemed to consume American society.

I like to think of him as the closest thing the US ever had to a restoration era fop, in the manner of the famous second Earl of Rochester, John Wilmot.

Like many arch-federalists of his day, as the 1790s drew on and turned into the early 1800s, he experienced growing alienation from the values and ethos of the young republic. Even as an editor of a vehemently federalist paper he felt inhibited from pronouncing his real opinions regarding the nascent republic. In a letter to his mother from April, 1797, exactly one year after assuming full editorial responsibilities for The Farmer’s Weekly Museum, he bemoaned: “In my Editorial capacity, I am obliged to the nauseous task of flattering republicans; but at bottom, I am a malcontent, and consider it a serious evil to have been born among the Indians & Yankees of New England.”[2]

As one of the first to disassociate himself from republicanism and the American revolutionary tradition, he often groped for symbolism that seemed to him most at odds with revolutionary creed. Thus, in his choice of literary form and content Dennie showed a consistent inclination towards tropes that seemed to him most anathema to the cultural transformation he perceived around him and particularly to the commercial spirit of Americans. In this vein, Dennie had an obsession with the notion of ‘indolence’—in many of his essays he celebrated hedonism and laziness, as opposed to ‘industry.’ Fittingly, he was one of the first to openly attack Benjamin Franklin. “The economicks and the proverbs of this writer have been over rated,” he once wrote, those “who like to behold lightening lambent on iron, or to warm themselves at a dull stove, or to view a cock gasp in mephitick vapour will read Franklin.”[3]

Indeed, several decades before De Tocqueville, Dennie demonstrated considerable prescience by recognizing the historical irony of the political debates of the 1790s. While Hamiltonian Federalism championed commerce and industry, the competing American ideology, which synthesized much liberalism into its version of republicanism—for all its obsession with agriculture and its aversion to a nebulous idea of commerce—complemented the rise of modern market capitalism better than its competition. In one of his more reflective moments Dennie wrote, “restlessness is ever a capital defect in character… ‘Then where, my dear countrymen are you going,’ and why do you wander?”[4]

By 1800, when he moved to Philadelphia Dennie was already quite distraught by what he once defined as a “hogocracy” (“That is where an ignorant booby has blundered into a great estate, and has the riches, without the education, sentiments, or manners of a gentleman”).[5] Thus he turned to a more literary publication, (The Port Folio), in which he could recede from the despairing arena of politics. As editor of the magazine he presented himself to the public as “Oliver Oldschool,” which he contrived as a tribute to his favorite author, Oliver Goldsmith and a comical aside to those familiar with his peculiar literary persona—which combined youthful extravagance with old world and traditional sensibilities. In another letter to his mother he related his sentiments in unequivocal terms:

“Had the Revolution not happened; had I continued a subject to the King, had I been fortunately born in England

… my fame would have been enhanced… But in this Republic, this region, covered with the Jewish and canting and cheating descendents of those men, who during the reign of Stuart fled away from the claims of the Creditor, from the tythes of the church, from their allegiance to their Sovereign and from their duty to their God, what can men of liberality and letters expect but such polar icy treatment, as I have experienced.”

By the time Dennie died in 1811, the Port Folio had renounced partisan affiliation and the limited circle of people in America who kept the embers of old world gentility still glowing had receded from their prominent and conspicuous position in American life. Indeed, it would seem that the growing sense of melancholy and fatalism that scholars have discerned in the Port Folio paralleled Dennie’s own mental and physical malaise. As the years drew on Dennie, who had always struggled with poor mental and physical health, complained in letters and over the pages of the Port Folio of his deteriorating condition.

Several years after he died a friend of his wrote in memoriam, “Mr. Dennie was a gentleman of a refined taste and a fastidious sensibility, which attached him, not merely to the elegant in literature, but the elegant in manners, and which made him turn with equal disgust from a bald writer and a vulgar speaker.”[6]

[1] Joseph Addison wrote the famous ‘Spectator’essays together with Richard Steele.

[2] The Letters of Joseph Dennie, p. 159

[3] The Museum, 1/17/1797, p.1

[4] The Lay Preacher, The Museum, 5/2/1797

[5] “From the Shop of Mess. Colon and Spondee,”The Museum, 5/9/1797

[6] New England Galaxy & Masonic Magazine, 7/24/1818.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

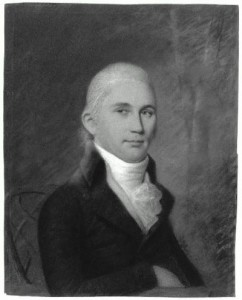

*lol* I love this painting of him; disdain and self-satisfaction captured in a subtle smirk. He looks like he’s just come up with a joke or one-liner and is thinking to himself, “oh yes; that’s very clever.”

Good read, thanks! On early American cosmopolitanism, Thomas Boylston Adams’ editorial involvement, and The Port Folio’s serialized publication of his brother John Quincy’s “Letters on Silesia,” you may also enjoy: Linda K. Kerber and Walter John Morris, “Politics and Literature: The Adams Family and the Port Folio,” The William and Mary Quarterly

Vol. 23, No. 3 (Jul., 1966), pp. 450-476.

Thanks, I should have added some references for folks who might be interested. Also Catherine O’Donnell Kaplan’s “Men of Letters in the Early Republic” and William Dowling’s “Literary Federalism” are good for anyone interested in reading more about Joseph Dennie.