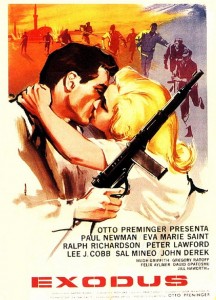

I began research on this post thinking I was going to write about Otto Preminger’s 1960 film adaptation of Leon Uris’s Exodus (1958) as a biblical epic. The case is not that hard to make: the title is a pretty strong clue, as is the setting—the “Holy Land.” And two extraordinary scholars have already essentially made this case: Melani McAlister in her pathbreaking Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and U.S. Interests in the Middle East since 1945 (2005; 2001) and Amy Kaplan in “Zionism as Anticolonialism: The Case of Exodus” (2013).[1]

I began research on this post thinking I was going to write about Otto Preminger’s 1960 film adaptation of Leon Uris’s Exodus (1958) as a biblical epic. The case is not that hard to make: the title is a pretty strong clue, as is the setting—the “Holy Land.” And two extraordinary scholars have already essentially made this case: Melani McAlister in her pathbreaking Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and U.S. Interests in the Middle East since 1945 (2005; 2001) and Amy Kaplan in “Zionism as Anticolonialism: The Case of Exodus” (2013).[1]

But in browsing through IMDb, I began wondering if the post-WWII biblical epic exists at all, at least as a distinct and separate genre.[2] Most critics and scholars would surely agree that it makes no sense whatsoever to enforce canonical orthodoxy on Hollywood and separate films like The Ten Commandments or Samson and Delilah (1949) that are “based” on actual scriptural sources from apocryphal works like The Robe (1953) or Ben-Hur (1959) or Barabbas (1961)—films about characters who encounter Jesus in some way. Ben-Hur is blatantly just as much a biblical epic as King of Kings (1961).

But does it make sense, then, to draw a line in the sand (pun intended) between these biblical epics and the sword-and-sandal epics that Hollywood was also churning out at that time, films like Spartacus (1960) or Cleopatra (1963)? Films about ancient Greece and Rome thrived alongside these films made from or inspired by the Bible. We cannot, surely, call them biblical epics, but maybe there’s something grander that encompasses them both—a supergenre, so to speak?

As I began to follow Ariadne’s thread through the labyrinth of common casts and production teams, I came to the conclusion that there was really a transnational genre of films made between 1949 and 1972 that we might call “the mediterranean,” much like “the western.” For that is really what unites these films: their Mediterranean setting.[3] The biblical content of some of these films is, in fact, secondary and, in a sense, contingent: biblical stories are just one way of telling mediterranean stories, much as the cattle drive was one possible plot for the Western.

What stands out is not the content at all but, we might say, the temperature. Lustiness and voluptuousness are the absolute sine qua non of these films. These films are about bodies—muscles, curves, and sweat—and also about bodies in extremis—in a state of, one might say, torture or tumescence, agony and ecstasy. These are hot films from a hot climate: films about swarthy bodies and sultry eyes. These are films exploring what can be done with light clothing that is sweated through easily, much as today’s superhero films are explorations in spandex.

In fact, mediterraneans can be seen as a closely analogous cinematic form for the 1950s and 1960s to the superhero and disaster movies of the past 10-15 years, which we should probably also see as a single supergenre, united by their common focus on images of massive urban devastation. Like today’s disaster/superhero films, mediterraneans were the films on which studios lavished money both in production and in publicity. Both genres also tended toward marathonic length: they offered quantity to the viewer above all. There are also technical analogies: both genres used special viewing technologies—Cinerama and CinemaScope then, IMAX and 3D now—to entice viewers into buying premium-priced tickets.

And like the superhero/disaster genre, the casting was both repetitive (the same stars appearing in film after film) and transnational. But because of the generic constant of a Mediterranean setting, the mediterranean film’s cast and crew was not truly global—as the superhero/disaster film is increasingly tending to be—but prioritized Mediterranean or Mediterranean-looking actors and actresses: Charlton Heston, Sophia Loren, Victor Mature, Anthony Quinn, Kirk Douglas, Hedy Lamarr, Burt Lancaster, Gregory Peck, Jean Simmons.[4]

By cross-referencing these actors’ filmographies, we begin to see that “the mediterranean” as a genre really was not bound by temporal setting at all: it makes little sense to exclude Zorba the Greek (1964) or El Cid (1961) given that they abound in the same sweaty-sexy-epicness as those films set in antiquity.[5] And, pushing the envelope some more, I think we also have no reason not to acknowledge that the extraordinary efflorescence of Italian cinema at this time—Fellini, Antonioni, Pasolini, the post-neorealist versions of De Sica and Rossellini, Visconti, Leone,[6] and Monicelli—was an integral part of the mediterranean genre as well, as were the voluptuous stars they employed, even if they weren’t wearing togas. Anita Ekberg, Brigitte Bardot, Monica Vitti, Claudia Cardinale, Gina Lollobrigida, Ava Gardner, and others named above were the anchors of a transnational constellation of cinematic sex that re-traced the shores of the Mediterranean, from the Côte d’Azur to the Nile delta, often set to the strings of Nino Rota, whose most famous scores Stateside would be Romeo and Juliet (1968) and The Godfather (1972).[7]

But as we follow these actors’ careers, we also begin to see that, unlike the prior emigration of Northern European talent to the US between the wars (Dietrich, Jannings, Garbo, Bergman, Sternberg, Lang, Preminger, et al.), there was no one-way importation of starpower. American film stars appeared relatively frequently in Italian- or Greek-financed productions.[8] The relationship between Hollywood and Cinecittà, the Italian film production hub, was not one-way but a circuit—a relationship that is the subject of Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (1963), which itself was produced by Carlo Ponti, who along with Dino de Lauretiis and Roger Vadim bankrolled much of this Mediterranean-Hollywood collaboration.[9]

Now, what does this have to do with Exodus? Well, I think we can look to Exodus to begin explaining the immense popularity of this genre. For Exodus, in fact, narrativizes the ideological work that I think this whole genre performs: it shifts the West’s cultural center of gravity decisively, re-grounding and revitalizing the whole idea of Civilization in the passions of the Latin South rather than the sophistication of the discredited Teutonic North. “Culture” is no longer icy Kultur

Exodus is about this cultural pivot: it is about realizing that there is nothing left for the Jews in Denmark or Britain or France or Germany or Austria or Poland—Jews emigrate from all these places in the novel. Its massive success (millions of copies sold, #3 for the year at the box office), however, suggested that this pivot chimed with more general American feelings about the cultural geography of Europe.

The mediterranean genre, I’d argue, was a way for Americans—Jews and Christians alike—to swing from an interwar geography that emphasized the U.S.’s ethnic and cultural roots and affinities with Northern and Central Europe to a postwar geography that played up the nation’s temporally deeper roots in the Mediterranean world as part of a common and even primeval civilizational heritage.

For American Jews this swing was particularly urgent: re-connecting to the Mediterranean allowed them to disconnect from Central and Eastern Europe, from what Timothy Snyder has called the “bloodlands” between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. The mediterranean genre allowed Jewish-Americans to imagine a history of Judaism that blocked off the world of Yiddishkeit, that denied that the shtetl had ever been home. During this period, to be sure, the popular culture rehabilitation of Ashkenaz would begin (with the Broadway premiere of Fiddler on the Roof in 1964 and its film version in 1971), but until the mid-1970s (marked, perhaps, by Irving Howe’s World of Our Fathers in 1976) positive images of Jews remained almost wholly anchored in the Mediterranean.

The Zionist implications of this geographic reorientation are obvious, and there is nothing subtextual whatever about Uris’s novel and its film version as far as that goes: the point of the novel is to instruct American Jews that aliyah—immigration to Palestine—was the only reasonable course of action for European Jewry before the Shoah and, apart perhaps from an indefinite sojourn in America, the only reasonable course to set in its wake.

But I want to argue that despite the exceptionalism that comes with this Zionist argument, Exodus is not just about Israel or even just about the US and Israel. It is really part of an enormous and unrecognized cultural pivot to the culture of the Mediterranean after the Second World War, a desire for a common cultural heritage that would solidify and perpetuate the tentative steps toward “Tri-Faith America” and the “Judeo-Christian tradition” that had been taken before World War II. Exodus, like Spartacus or Ben-Hur, was about renewing “Western Civilization” as a more “Southern Civ”—as a combination of Athens, Rome, and Jerusalem, and an excision of Berlin and its satellites, which for Uris included London.[11]

The medium for this renewal could hardly be doctrinal or even, in the narrow sense, intellectual. The cinema stepped in—by accident or by intention—to provide a better medium: sex. While the sexual tension of Exodus is fairly low, the mediterranean genre turned up the heat on the Western Civ crucible to something just short of incandescent.

[I’ve created a list of some films that fall into the mediterranean genre here.]

[1] Kaplan’s focus is not really on the similarities or continuities of Exodus with biblical epics, but it’s a fabulous essay that builds off many of McAlister’s points while also emphasizing the importance of Uris’s overt analogy between the Zionists’ struggle against the UK and the American Revolution.

[2] As Ben points out in Monday’s post, the biblical epic is indeed one of the oldest genres in cinema, but after the silent era it went through a long dry spell commercially. There was not a single top-ten box office hit belonging to the genre between 1930 and 1949, when Samson and Delilah set the country on fire. I would argue, therefore, that S&D effectively “rebooted” the genre, but no longer as just “the biblical epic.”

[3] Coincidentally(?), this periodization fits perfectly onto the years between the French version of the first volume of Fernand Braudel’s epic La Méditerranée et le Monde Méditerranéen a l’époque de Philip II in 1949 and the English translation began appearing in 1972. Hence the title of this post.

[4] I don’t understand how the latter two actors—Peck and Simmons—passed for Mediterraneans, but they were repeatedly cast in these films.

[5] There is a real sense in which Hollywood films set in Mexico are in fact mediterraneans: they often feature many of these same actors and emphasize the same brand of earthy sexuality. Also see footnote 11 below.

[6] Leone in fact apprenticed on the sets of Ben-Hur and Quo Vadis in Cinecittà, and himself made two “sword-and-sandal” films—called peplum films in Italy—before his “spaghetti westerns”: The Last Days of Pompeii (1959) and The Colossus of Rhodes (1961).

[7] Pasolini is a wonderful example of the insufficiency of the “biblical epic” as a self-sufficient category; not only did he film The Gospel According to Matthew (1964), but also adaptations of Oedipus (1967), Medea (1969), and The Decameron (1971).

[8] The most famous instance probably is Burt Lancaster’s appearance in Visconti’s The Leopard (1963), though even earlier Kirk Russell had appeared in an Italian production of Ulysses (1954).

[9] Godard wanted Sinatra in the role that Michel Piccoli would eventually fill. The film-within-a-film that the characters are working on is an adaptation of the Odyssey.

[10] Even Ingmar Bergman began in this earthy vein, with the sultry Summer with Monika (1953) and the raucous Smiles of a Summer Night (1955).

[11] In this sense, despite the vicious and pervasive racism of the book and the film toward its Arab characters, it is imprecise to accuse the novel and film of Orientalism because the operative opposition in the story is not West and East but rather North and South (another reason that films set in Mexico belong in this genre: the N-S alignment is dominant in them as well). Aliyah is only secondarily eastward for most of the characters: what is essential is moving southward to the Mediterranean and out of the chaos of the Northern half of Europe. On the other hand, David Lean’s epic films Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965), though completely contemporaneous with the high point of the biblical epic, are clearly Orientalist in a classical sense—the dominant trajectory of both films is latitudinal, not longitudinal. An easy way to distinguish Orientalism and mediterraneanism: in mediterraneans, the bad guys have British accents.

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andy, this is a fantastic reading. I think you are absolutely right to see all of these films as partaking of this larger genre, and right too on that “pivot” to situate the energy and vision of “Western civilization” in a mediterranean clime.

I would say that these films also — maybe as part of that project? in tension with that project? — draw from and perpetuate an Orientalist imaginary. (At least I think that’s true of the Biblical and barely-Biblical epics.) I’m mulling over how the Orientalism of the genre fits with your argument about how these films portray “the Mediterranean” as the animating mind or spirit of the West. If you — or any readers — have thoughts on that, I’d be interested to hear them.

To be clear, I’m thinking that the way you’ve framed the project here — a project of relocating the West — may have to be a project of re-orienting the West — that is, intrinsically Orientalist. So I might go farther than you do at the end there, but it may also be the case that the Orientalism is somehow “gratuitous” or at least not essential to the aim of these films, in the sense that (as you suggest above) some are arguably Orientalist and others not. Does that make any sense?

Wow. This is impressive. I’ve thought a lot about Western civilization in the context of the great books idea, but this never occurred to me.

In other places I’ve argued that the great books idea, as it developed after World War I, could be seen as a sign of what I called a growing “Western cosmopolitanism”—an effort by American thinkers to look more consciously to Europe for a less parochially American worldview. But I never posited a North-South European split. I bring this up because I wonder if that Western cosmopolitanism in the academy and adult education fed the minds of the audience for these post-war films (i.e. made them receptive to a new *kind*/revision of Western civilization).

Anyway, that’s off-the-cuff thinking. Thanks a million, Andrew, for this GREAT post. One of the best I’ve seen here—and certainly a stand out contribution to our so-called “biblical epic” week. Perhaps this is a post looking for a publisher and much expansion/elaboration? – TL

I’ve only read the opening paragraphs of the post (will come back later and read the whole thing), but I just want to say that the post’s title deserves some kind of award for sheer cleverness (a word I use here in an *entirely* complimentary way!).

Thanks, everyone!

L.D.,

Orientalism was constantly on my mind as I thought about this post, but I decided that it is not an accurate term for what is going on in these films. The Mediterranean people of these films are generally not, to use one common theme of Orientalism, inscrutable: their desires, motivations, agendas are very easily scruted indeed! The focus is not on mystery but on passion. The sexuality on display is not, I think, framed as some exotic or decadent, deviant sexuality threatening European culture, but rather its primal root. At least, that’s what I’m seeing in these films. OTOH, I noted that many of these actors were also in films that we can only construe as Orientalist–for instance, Anthony Quinn played both Attila and Kublai Khan, in addition to Zorba, Zapata, and Osceola. There’s a massive compression of all non-white peoples going on there, but I’m just not sure that whatever that is can be called generally “Orientalism.”

Tim,

I think “Western cosmopolitanism” probably played a very large role in preparing the way for the mass enjoyment of these films. I was thinking throughout of the way that your arguments about Adler and the Great Bookies and Kevin Schultz’s argument about Tri-Faith America are so central to describing what audiences of the time may have been seeing when they went to the cinema for one of these films: that US culture had a deeper and more diverse root system than just Northern European Protestant culture.

Great post!

I found it particularly interesting that you compare this genre with the super hero genre. It’s quite interesting that this project of revitalizing post war Judeo-Christian identity through sex parallels the dynamic at work during the heyday of superhero comics–when Jewish writers created superhero alter egos like Superman to revitalize their bodily images and of course as a means to get the shiksa (Lois Lane).

Thanks, Eran! I think those two dynamics–the desire to change the image of the Jewish (male) body and the assertion of Jewish male desire for non-Jewish women–are certainly at play in these mediterranean films (a lot of the femmes fatales–Delilah, the Queen of Sheba, the woman who has the hots for Moses in Ten Commandments–are explicitly marked as non-Jewish).

But I think that in some ways the early Superman is the opposite of what these films are doing. Superman’s about whether a literal alien can successfully pass and assimilate among ordinary Americans, whereas I think the ideological work that the mediterranean films are doing is to push mainstream (WASP) American culture to recognize its deep roots in these “swarthy” but (by then) “white” ethnicities–Jews, Greeks, Italians, and, to a lesser extent, Spaniards. But then again, I don’t know the Superman story all that well–there’s an interesting-looking bio of Siegel and Shuster that I want to read, though: http://us.macmillan.com/superboys/bradricca

And yet Superman comes to earth in the 1930s as the embodiment of that decade’s “Nordic ideal” (see Gary Gerstle, American Crucible, Chp. 4)

I think Steve Whitfield from Brandeis wrote about this somewhere, though I can’t find it in a quick google search.

This also remind me of the awesome Seinfeld Shiksappeal episode:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vLRT47mvBig

Andy – You may already have implied the point in alluding to Kevin Schultz’s work, but the mediterranean shift you describe in this excellent post may have some congruence with the salience of so-called “white ethnics” in the culture and politics of the 60s and 70s, not that all the groups included in the designation had that territorial identification. That shift reduced the difference and distance between them and those who saw themselves as non-ethnics, enlarging “the circle of the we” by modifying the complexion of the West, while falling far short of portraying the latter as alien to it. The narrower intellectual aspect of all this might encompass histories of concepts of ethnicity, minority and culture.

Good points, Bill.

Bill, I think that is definitely what is going on in this genre, and I should have been more explicit in naming it as a question of ethnicity. There’s a whole interesting genre of novels or memoirs by some white ethnics just before this–I’m thinking of George and Helen Papashvily, or William Saroyan, or Louis Adamic–that made a considerable impression on “WASP” America, and probably prepared the way for the success of this film genre.

Agreed, Bill. I was thinking of The Godfather films as accomplishing the ideological work Andy describes here. But, then again, I rely too heavily on Gary Gerstle’s American Crucible (see Chp. 8).

FWIW, regarding The Godfather, Fredric Jameson has a brilliant reading of the films’ utopian function in his “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture” that fits right along these lines:

“In the United States, indeed, ethnic groups are not only the object of prejudice, they are also the object of envy; and these two impulses are deeply intermingled and reinforce each other mutually. The dominant white middle-class groups–already given over to anomie and social fragmentation and atomization–find in the ethnic and racial groups which are the object of their social repression and status contempt at one and the same time the image of some older collective ghetto or ethnic neighborhood solidarity; they feel the envy and ressentiment of the Gesellschaft for the older Gemeinschaft which it is simultaneously exploiting and liquidating.

“Thus, at a time when the disintegration of the dominant communities is persistently “explained” in the (profoundly ideological) terms of a deterioration of the family, the growth of permissiveness and the loss of authority of the father, the ethnic group can seem to project an image of social reintegration by way of the patriarchal and authoritarian family of the past. Thus the tightly knit bonds of the Mafia family (in both senses), the protective security of the (god-)father with his omnipresent authority, offers a contemporary pretext for a Utopian fantasy which can no longer express itself through such outmoded paradigms and stereotypes as the image of the now extinct American small town.”

Greetings- two more films for you:

Jules Dassin’s “Never on Sunday [Pote tin Kyriaki]” (1960) with Melina Mercouri, and less obviously, Alexis Solomos, an important theatrical director who studied with Erwin Piscator.

Also The de Sica/Neil Simon “After the Fox” (1966) with Peter Sellers, Victor Mature and Marty Balsam.

Both involving Americans loose in the Mediterranean.