The following guest post is by Mark Edwards, assistant professor of US history and politics at Spring Arbor University in Michigan, author of

The Right of the Protestant Left: God’s Totalitarianism, and co-chair of the recent 2014 S-USIH Conference.

I was born and bred in rapture culture. Chick tracts were my Marvel comics (btw, be sure to download the Chick tracts app to your phone so you can see what happens to Charlie’s ants when they die!). For some Christian young people today, growing up as a potential Leftover is tough. When discussing fundamentalist readings of the end of days last semester, one student betrayed his deepest childhood fear: Whenever he was left behind in a room by his parents, he cried, worried that they had been taken up. For me, on the other hand, the rapture was my ticket out of a financially unstable working-class family as well as out of having to deal with the uncertain world beyond grade school. I was counting on those 88 Reasons Why the Rapture Will be in 1988 (Edgar Whisenant’s book sold over 4.5 million copies) since that was the beginning of my senior year. Alas, the rapture didn’t occur. At least I don’t think it did: Has anyone seen Phil Collins lately? Maybe in the air tonight?

The hyper-systematic theology of dispensational premillennialism that undergirds rapture culture has become of increasing interest to scholars—the term “rapture culture” itself comes from a wonderful book of the same name by Amy Johnson Frykholm. Matthew Avery Sutton’s just-released American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism (Harvard 2014) is sure to become a definitive work in this field. Similar to other recent studies by Daniel Williams, Darren Dochuk, and Bethany Moreton, American Apocalypse

tells of the long origins of contemporary evangelical conservativism (Sutton starts in the Gilded Age). Unlike Dochuk and Moreton, however—who share the new political history’s attention to “corporate populism” (Moreton’s term)—Sutton focuses on the power of ideas to determine political action, and vice versa. That theme was evident in Sutton’s 2012 essay “Was FDR the Anti-Christ?” which won the JAH’s best article award and is now a chapter in American Apocalypse

. There is much to commend Sutton’s book to intellectual historians, as has already been revealed in several early reviews and, I prophecy, will be made plain in several future venues including this blog. For now, I need to get to the point of this post.

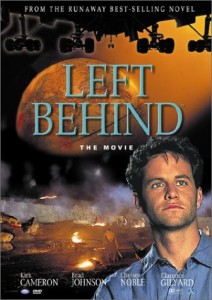

To what extent can rapture culture’s greatest accomplishment, the Left Behind franchise of books, t-shirts, role-playing board and video games, and most importantly the movies, be considered Biblical epics? Or, perhaps better, why AREN’T the films considered to be so? Because they are not as “Biblical” as the Exodus or Ten Commandments? Because the very category of Biblical epic assumes premodern source material heavy laden with sensuous hulks—no planes, trains, or automobiles allowed; and certainly not Kirk Cameron or the Ghost Rider? These questions get at the boundaries of what is accepted as “tri-faith” ecumenical religious entertainment versus sectarian fantasy that we pretend lacks cultural capital but doesn’t at all.

As Sutton’s book reminds us, white Christian Americans have been enraptured by Left Behind ideology to an extent that they never were by the Exodus story. And as Ed Blum has recently and brilliantly observed, white America’s refusal to go down with Moses to liberate its many captives at home and abroad is a most epic fail.

23 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I think you’re right, Mark, that the entire idea of the “epic” is much to do with Homer and how Homer’s work has been perceived around the world. Are “Eastern Epics” or “African Epics” ever discussed in scholarly or popular works (or so-called “Oriental” v. Western Epics)? I ask because it *seems* that the idea of the epic is perhaps rooted in the Mediterranean world. And those roots give the idea a flavor of Mediterranean sensuality, or a sensibility?

With regard to epics and the bible, if the term is rooted in ancient Greek culture, then whether or not a Judeo-Christian-Islamic monotheistic-type story fits into the “epic mode” is only an accident to the former’s production. And if that is so, then stories from the Koran/Torah/Bible would have to be modified, necessarily, to fit that style (hence the modifications we’ve discussed this week in various Biblical Epics). – TL

Great points, Tim! I guess I wasn’t thinking of the “biblical epic” much further back than the 1950s or maybe 1920s; how is the “biblical epic” as a film genre related to the literary/cultural tradition of the “epic?” Also, I was thinking of more generic uses of “epic” like “epic encounter”–which to me would be closely tied to “spectacle” in movie terms. My point was simply that the Left Behind industry seems to carry more cultural capital since WWII than do the films we usually associate as biblical epics.

Mark,

This is such a great and germinal post. One thing that occurs to me that had not occurred to me before is how resistant Hollywood and television is not only to sectarianism, but to anything that smacks of sheep-and-goats division. Its visions of the end of the world imagine general, indiscriminate tribulations, and the survivors of whatever cataclysm the film or tv show conjures up are ordinarily just lucky rather than chosen (or rejected). Often the survivors will have special skills, but that has more to do with the requirements of plausibility as to why they can survive rather than some metaphysical merit or status they might have.

I suppose this is a sound commercial strategy, but I also wonder if there is something else going on here? Why is Hollywood’s imagination of the apocalypse so secular?

So, would the flip side of this question–“Why is Hollywood’s imagination of the apocalypse so secular?”–be, Why isn’t Hollywood presenting more visions of the Apocalypse that are narrowly sectarian in their theology and that would be incomprehensible and meaningless to the vast majority of potential viewers, thus alienating them and failing in the process to separate them from their money?

Thanks, Andy! I’ll concede John’s point below about the commercial aspects of it all–if only Roland Emmerich would find Jesus! I haven’t watched the Leftovers (TV series) enough, but friends have compared it to a “secular rapture” theme. Would shows like the Leftovers have appeal apart from the evangelical rapture culture? Maybe.

My understanding was that the Nick Cage Left Behind was supposed to have more “cross-over” appeal. It’s out on blue-ray in early January; we’ll see. In the meantime, we can play the LB video games (the one with the most “prayer points” wins!!).

As to the boundaries of what makes a biblical film an “epic,” I think Melanie McAlister’s study of the Ten Commandments in her book Epic Encounters is helpful. She discusses how the term came about to describe the large scale and uniquely American ability (so thought, at the time) to reproduce on a massive scale the narratives of the Bible or eras contemporary to the Bible (Ben-Hur, for example). So it has to be big in various senses of the word. It also has to play as an analogy to contemporary issues and intersect with a number of other cultural texts of the period. McAlister is obviously more comprehensive, but I think this already may answer the question, or at least provide one important factor. Whatever else we might say about the Left Behind movie, its budget was relatively small and, even though it implied “epic” scale, its effects were poor for the late 90s/early 00s. Relative to other rapture movies it was a huge effort, but compared to contemporary “epics” of Braveheart and Gladiator, or biblical epics this year like Noah and Exodus, there’s really no comparison.

Game, set, match–Hummel

Hi John,

I should have been a little more precise in my language, but my point was that Hollywood not only avoids actual sectarian content, but avoids even the appearance of having sectarian resonances: you can’t take, say Terminator 2: Judgment Day, and decode it as validating or illustrating an actual Christian sect’s idea of the end times. “Judgment Day” is entirely secularized.

I’m not familiar enough with contemporary Hollywood to say whether it sure that “avoids even the appearance of having sectarian resonances” or not, though I have no reason to doubt it.

What I’m not clear about is, How is this an interesting question? We do not–or at least I do not–expect that Hollywood will be promoting “actual sectarian content” (outside of certain vanity projects such as Gibson’s “Passion,” which I would say proves the rule).

The reasons for that are, I suspect, quite obvious. If you push any definite theological content, you immediately narrow your consumer base to those who already agree with and want to hear more of that theological content.

Wouldn’t “the appearance of having sectarian resonances” have the same effect? To be sure, there are symbols that have become so well-embedded in our culture that they’re no longer owned by any particular sect or group–Christ’s crucifixion is a classic example. I don’t know that that has happened with any of the elements of end times speculations.

Unless theological content has become absorbed by the general culture in such a way that referring to it isn’t perceived as sectarian, it seems to me any embedded “resonances” would be lost on the audience, or, if they were ferreted out, would only serve to risk making the film less attractive to those uninterested in seeing a film promoting, however subtly, sectarian beliefs.

Hi John,

So first of all, your claim that there are no apocalyptic “symbols that have become so well-embedded in our culture that they’re no longer owned by any particular sect or group” is wrong. I’ve already mentioned one–Judgment Day–and I can immediately think of two more: the Antichrist and the Four Horsemen.

But, and here’s my point, there’s no blockbuster Hollywood film that purports to be based on Revelations the way that there are films that purport to be based on Exodus or Genesis or Judges or the Gospels. (Left Behind–either version–is not produced by a large Hollywood studio or even by a major independent film production company.) Sectarian differences over those books haven’t stopped Hollywood from making films “based” on them.

Instead what we see are frequent invocations of “the Antichrist” or “the Four Horsemen” in films, but always in ways that have a clear separation from anything that can be construed as an affirmation of one type of millennialism or another (often they’re invoked shorn of any explicitly marked Christian connection at all), whereas filmmakers and producers are far less careful (or more brazen) about the filmed versions of Jesus or Moses or Adam and Eve.

I hope that makes my question a little more interesting to you.

Andy, when I say “interesting,” I am using it, not in the sense of “intriguing to me as an individual,” but in the academic sense of an “interesting question,” ie, one that promises, if answered, to reveal something important that was previously concealed.

I think you’re right that “Judgment Day” resonates in the general culture–I’m not sure how widely, or even more how deeply. But it resonates just enough that saying the phrase communicates that something serious is involved, which I suspect is all that was required for a title to a Terminator movie.

But perhaps I’ve missed your point, and even more, just am not up on what’s going on– I was unaware that there “are frequent invocations of “the Antichrist” or “the Four Horsemen” in films,” beyond, at most, the kind of very hollowed-out nods such as already mentioned with reference to “Judgment Day” (though, honestly, I can’t think of any involving “the four horsemen of the apocalypse”–Google tells me there’s a 1921 film of that title starring Rudolph Valentino, about WWI, and Vincente Minnelli remade the film, setting it in WWII, in 1962).

If your question has been, why “there’s no blockbuster Hollywood film that purports to be based on Revelations [sic],” I would think it would be due to the difficulty of coming up with anything like a compelling/coherent screenplay based on the book?

“….. whereas filmmakers and producers are far less careful (or more brazen) about the filmed versions of Jesus or Moses or Adam and Eve.”

I’m just wondering what some examples of this would be?, in terms of being more aggressively sectarian? I mean I imagine The Passion is widely taken to be Catholic, but that seems more due to the fame of its director than any fine point of theology in the film; as we learned from Tim’s post Gibson also did a lot to make sure evangelical leaders were on board with it.

And then just to grab another movie off the top of my head, the Last Temptation of Christ would be…Scorsese’s version of the scripture? What about the animated version of the Moses story, or the recent Noah film?, which is adorably weird in often bearing scant resemblance to anything *any* sort of Christian believed happened.

Just to be clear, I’m not arguing, I just realized I couldn’t come up with examples to illustrate your point, so I’m wondering what you had in mind or if these are more sectarian takes than I realized.

Robin Marie, sorry, that wasn’t clear. What I meant by “more brazen” was just that filmmakers are less concerned about where their portrayal of Noah or Moses or Jesus fits into the way various Christians (or Jews) might interpret these figures, whereas no one seems to willing to take the risk of making a film that steps on the toes of specific interpretations of the Book of Revelation.

John,

Since in the same comment stream you’ve sic’d me and brandished how many degrees you have, I’m not sure we’re going to get anywhere. I don’t like pissing matches.

Sorry, I only meant it to be a humorous allusion to the uselessness of knowing anything about the Bible eg when navigating popular culture.

As for the “sic,” what can I say? It’s “The Revelation of (or to) St. John,” singular. “Paul’s Letter to the Romans” eg is plural because there was more than one Roman. I didn’t invent the distinction.

As for why we have movies of Jesus and Noah and Moses and not of Revelation, do you really think it’s because film makers are more worried about the reactions of devotees in the latter case than in the former?

Doesn’t it seem more likely that Revelation, being a kind of kaleidoscopic collection of not always-transparent symbols and such (Calvin eg never wrote a commentary on it because he confessed he had no idea what was going on), resists the transfer to film, whereas the other stories are more, well, story-like, and more easily adaptable to a screenplay with comprehensible chronology, character development, tension, and etc.?

Also, what are we to make of the weird genre of film that involves Biblical themes and plot lines while remaining weirdly distant from any scriptural seriousness and, in effect, is a thriller/horror movie? I’m thinking along the lines of Stigmata or Ninth Gate.

It’s entirely possible the answer is that these are easy, cheap films make for easy, cheap thrills and utilizing broadly shared cultural ideas of devils, demons, and supernatural possession does the job easy and cheap, and that’s about it. I mean that actually could be it, but it would be more fun if someone was able to make more of it.

My two seminary degrees aren’t helping me recall where there’s a “Ninth Gate” in the Bible . . .

Oh there isn’t! That’s my point. That movie is vaguely based on Christian belief because it involves a Christian version of Satan — but then it adds all this stuff, the vast majority of it, that has nothing to do with the Bible. So that’s exactly what I mean. It’s very possible there’s nothing more to it than what I sketched before. But I’m just wondering if we can say anything more about the regularity with which these kind of films are released.

Which raises a question: Are Biblically or religiously-themed films all that different from other genres in the degree to which they mangle and misrepresent the events or narratives they address?

Westerns rarely gave us anything but a ridiculously inaccurate view of life in “the west” after the war; “The Patriot” isn’t full of great insights into the revolution; “Moby-Dick” might not deal very carefully with the whaling industry; and etc.

Paul Fussell, a veteran of WWII, said take the first 15 minutes of “Saving Private Ryan” and use it as a stand-alone film called “Omaha Beach: Aren’t You Glad You Weren’t There?,” but throw the rest away.

I’m reminded of the story about John Huston wanting to work a woman onboard the Pequod so he could get a romantic triangle going between her and Ishmael and maybe Stubbs, to make the film more conventionally appealing.

Films need to have a lot of predictable elements in them to be “blockbusters.” I suspect that’s why it’s as unlikely you’ll see a film based on the Book of Revelation as you will one based on one of the Epistles to the Thessalonians . . .

Ok so now that I’ve been sitting there thinking of your question Andy I think I have a half-baked attempt at a (possible) factor. Sorry for this being the third comment in a row, teaches me to sit and think for a while before I write these.

Anyway, what I was thinking is that it seems to me that the numerous amount of films based on the rest of the Bible, and the relative few based on Revelations, might have a lot to do with the cultural politics of talking about the End Times. Insofar as secularization is a thing — and let’s not get into that now! — it does seem that one effect of it is not so much that people raised in a Christian tradition or, very loosely speaking, Christian culture, lose their faith in God or even the divinity of Christ, but more often that they soften these beliefs and make them generally more pluralistic. So, it is a lot easier to find someone one the street who believes that Jesus was some sort of divine (and they might think so was Buddah, or Muhammad, etc) than it is to find someone on the street who will say to your face that if you don’t believe in Christ then yeah, you’re going to hell. (Or are going to be left on the wasteland of earth during the rapture, or whatever). There’s just simply fewer of those around (at least in California!)

So, from a commercial point of view, it makes perfect sense to avoid really drawing out the full story in detail, rather than just making vague gestures toward the kind of end times motifs most people resonant with out of instinct from growing up in a Christian-majority country. Who wants to go see a movie that implies – or just plainly argues — that they might be going to hell? Not many; especially if the gist of the film is not to draw you into the plight of an Every Man, but to poke at your side the whole time implying that the end times won’t be about every man, it will be about saved men and condemned men!

On the other hand, who wants to go see a movie about what an awesome dude Jesus was and how his message of love changed the world? Lots more people. Now that sounds like a pick-me-upper. Even The Passion, with all its violence, ultimately ends on a note (literately; from my memory the swell of the music playing while Jesus gets up from the tomb and the credits roll is fabulously intense) of hope and transcendence.

And then this whole discussion could go into how such messages are also much more compatible with capitalist culture, but, I would be getting ahead of myself and over my head if I went there.

@Andy per your reply above: Right, and it wasn’t entirely your fault; after I reread what you wrote I got what you meant!, blargh.

My guess is is that filmmakers are not so much avoiding a risk of offending Christians when they avoid a more aggressively Biblical Revelation film; as we’ve been throwing around here, it seems more like they are avoiding the risk of low box-office sales, or, I would think, offending more secular audiences. The numbers of people willing to go see a movie about Jesus offsets the cost of offending some particular Christians; but as I said, I don’t think an equivalent audience exists for movies about how half the population (or whatever) is going to go to hell.

It’s important to keep in mind that Rapture-culture films like “Left Behind” are not simply based on the book of Revelation, but on a complicated pastiche of Revelation, Daniel, and other bits of the Bible. A straight-forward depiction of the text of Revelation wouldn’t provide much of a plot. (Not incidentally, this is a situation that Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins have struggled with in their books.) But the incorporation of prophetic visions from the Old Testament into an allegorical text about first century CE events allows for a more coherent and action-oriented narrative that has gripped readers for more than a century. This construction helps to explain why a mainstream film hasn’t been made: apocalypse narrative is by its nature sectarian. Ask two dispensationalists about the order of end-times events, and you’ll get different answers.

As for the “biblical” portion of the “biblical epic” question regarding “Left Behind,” these films are considered by their producers and a significant number of potential viewers to be explicitly biblical in the sense that they precisely describe the events predicted by the Bible that will necessarily occur any day now. But because that narrative is a relatively new one and cannot be found in one piece anywhere in the text of the Bible, it doesn’t carry the same weight of “biblical-ness” that the relatively simple stories of Genesis and Exodus do. Although, I can’t recall any Old Testament films that depict the creation of the Earth and then back up and depict it again with a slightly different order of events.

Thanks for these reflections, Charles (and everyone, for that matter). It’s interesting how the line of comment has raised the issue of “sectarian” versus “ecumenical/interfaith” entertainment. For some years now, we’ve been scared that the sectarians (fundamentalists) are taking over the country, White House, Congress, military, and so on. Others, like David Hollinger and his students, tell us that liberal Christianity has actually carried the day in the form of increased tolerance, pluralism, etc. What do the “biblical epics” tell us? Does Nick Cage’s failure to captivate America in the LB reboot suggest that Hollinger is right? Or, only that the fundies gained political capital apart from (or even at the expense of) cultural capital?