Blame Andy Seal. He made a brief observation that American civil religion might exist in films such as Nicholas Cage’s National Treasure by folding together U.S. history and the exodus story. My obsession regarding civil religion got the best of me as I thought about suffering through a viewing of that film. But, lo! instead I stumbled upon a more substantial “treasure”–Kirk Cameron’s Monumental: In Search of America’s National Treasure (2011). While ostensibly a documentary, Monumental provides a remarkable fictional account of America’s origins [you know, the single origin story that we all believe in], while delivering an equally remarkable glimpse into a certain American evangelical mind that demands a conflation of the exodus story with the origins of the United States.

The film opens with Cameron sitting in a suburban backyard, staring. He stares and stares as the first few minutes of the film are intercut with scenes of talking heads telling us how terrible conditions are in the United States and how desperate its role in the world has become. In a voiceover, Cameron worries about our apocalyptic moment and in sequence that supports Matt Sutton’s argument regarding “radical evangelicalism” in his new book American Apocalypse, Cameron asks whether we should heed the advice of other evangelicals who tell him not to worry that “the world is headed to hell in a hand basket” because the apocalypse will fulfill the prophecy of Jesus’s imminent return. But Cameron is not waiting for that moment, he’s got kids (!) and believes that giving up on his country will make the world worse for those he loves AND not necessarily bring about the second coming of Christ. So now we understand why Cameron was staring as the film begins–he has vision. He sees a way beyond America’s hell. The Pilgrims! he declares, will lead us to a new promised land if only we can embrace their wisdom by reclaiming their story–yes, singular, yet again–Cameron and his interlocutors, including David Barton

, are unimpressed disagreeing narratives, interpretations, and historical debate of almost any kind.

I suppose Cameron could have cut to the chase and saved time by heading straight to the monument that inspires the title of the film, but he chose to take viewers on a historically inaccurate tour of the Pilgrims trip from England to the New England, and so begins by physically showing up in one of the small English villages where the Pilgrims congregated. His study abroad is a ruse, though, meant only to emphasize that WE MUST UNDERSTAND that the Pilgrims’ “escape” from the Old corrupt world of kings and false faiths is the same kind of exodus story found in the Old Testament. Glossing over the internal divisions of the group aboard the Mayflower and underplaying the pragmatic nature of the group, Cameron finds everything that befalls the Pilgrims as divinely inspired–an understanding of events that even the Pilgrims would have rejected not to mention the other peoples who also had an interpretation of this time. Linford Fisher’s

work on the intersection between European faiths and Native American religions offers a hard-hitting corrective here.

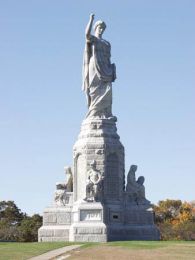

No matter, the achievement of the Pilgrims must be as profound as possible in order to set up the centerpiece of the film’s argument, that their history can be used as a “training manual” to know how to live today. Marshall Foster of the humbly named World History Institute (teaching the biblical–read Christian–foundations of liberty) serves as Cameron’s tour guide for a visit to the National Monument to the Forefathers in Plymouth, Massachusetts. This massive granite statue appears in the movie as a kind of lost ark of the American covenant. Here we find inscribed into its hard stone facade the truths that have and can once again lead Americans to greatness…or something like that. One of the official (and therefore troubling) tourism sites for the state of Massachusetts explains:

No matter, the achievement of the Pilgrims must be as profound as possible in order to set up the centerpiece of the film’s argument, that their history can be used as a “training manual” to know how to live today. Marshall Foster of the humbly named World History Institute (teaching the biblical–read Christian–foundations of liberty) serves as Cameron’s tour guide for a visit to the National Monument to the Forefathers in Plymouth, Massachusetts. This massive granite statue appears in the movie as a kind of lost ark of the American covenant. Here we find inscribed into its hard stone facade the truths that have and can once again lead Americans to greatness…or something like that. One of the official (and therefore troubling) tourism sites for the state of Massachusetts explains:

The monument was created to honor the ideals on which Plymouth Colony was founded; faith, education, law, morality, and freedom. Faith is represented by the central standing figure, a woman with her right hand extended to the sky and her left hand holding the bible. The front panel is inscribed with the following dedication: “National Monument to the Forefathers. Erected by a grateful people in remembrance of their labors, sacrifices and sufferings for the cause of civil and religious liberty.”

According to Foster, who eagerly provides Cameron and the rest of America’s disaffected Christians an interpretation of Christianity’s foundational role in U.S. history, the massive statue designates the American version of a crossing as profound and historically significant as the Jewish exodus through the Red Sea. And while the figure of a woman dominates the monument, Foster and Cameron focus their attention on a bare-cheasted man who sits guarding the monument; he is a figure Cameron and Foster call “liberty man.”

Liberty man is the masculine protector of what Foster refers to as the “matrix of liberty”--a system of ideas that are engraved into the monument to remind Americans of their righteousness. Liberty man wears a lion skin, wields a sword, and holds broken chains in his left hand, leading Cameron to blurt out, this is “not a wimpish religious guy. He is a stud!” Indeed, and that stud is ready to act violently on behalf of his righteous legacy–no matter how misguided and false.

Liberty man is the masculine protector of what Foster refers to as the “matrix of liberty”--a system of ideas that are engraved into the monument to remind Americans of their righteousness. Liberty man wears a lion skin, wields a sword, and holds broken chains in his left hand, leading Cameron to blurt out, this is “not a wimpish religious guy. He is a stud!” Indeed, and that stud is ready to act violently on behalf of his righteous legacy–no matter how misguided and false.

We have a long line of Hollywood hunks who have played the studs of the bible, but liberty man, encased in hard granite, is far more disturbing. Sitting aloft at a size that is comparable to Charlton Heston on the big screen, liberty man protects a legacy that is the bane of American history and the dark side of civil religion. He represents the misplaced admiration for the early European communities that Jill Lepore, among many others, has attempted to dismantle. He defends the whitewashed view of native tribes that continue to echo in classrooms across the United States and through generations teachers. He promotes the misguided view of Christianity’s role in the founding of the United States that David Sehat among others has tackled. However, for me, because I work on civil religion, this monument and Cameron’s identification of liberty man as masculine and violent perpetuates the often catastrophic justification of defending national ideals through war. Cameron ends his film no longer staring blankly out but clear eyed, with purpose and conviction–convinced that having discovered the true origins of his country he is ready to fight for his vision, against whom is unclear. But freed from history and armed with ideas as calcified as the statue he vigorously admires, Cameron has produced a cinematic testament to a terrible American faith in its own self-rigtheouness.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

And just when you think it is impossible to dislike Kurt Cameron any more….*sigh* man.

I’m so glad to be the inadvertent inspiration of this post–your reading of the film is so fun and, of course, simultaneously sobering.

I’m over-reading this for sure, but one of the striking things about Cameron’s word choice to describe Liberty Man is its emphasis on procreative power–“stud,” which still,I think, carries some sense of animal husbandry. The blatant erasure of the Pilgrim women in the monument’s title underlines this patriarchal vision, which, as you point out, is also Cameron’s stated reason for not giving the U.S. up to its imminent destruction–his fatherhood.

So I’m wondering if this is a larger theme in the film, if Cameron actually makes an appeal specifically to fathers to save their families, or if his call is a more general one to all Christians. Basically, what place do women have in this film?

And thanks again for a really enjoyable post! I’m glad you saw this documentary so no one else has to!

On the one hand, the best response to this film is what Robin Marie writes–Cameron, again, sign. On the other hand, Andy, you have hit upon a thread that must be a default position among a specific tradition in evangelical thought, that the “fathers” have the fate of this world in their hands because they are in kinship with their ultimate “father.” What I found most interesting and disturbing was the close identification that Cameron and Foster had with a granite man. That statue comes to life in their telling of a past that makes their present militant. Their are marching forward armed, like their monumental leader, both figuratively and literally. When women enter the picture they are part of the group that understands the heroism required of the men.

I don’t know, Andy, I just get discouraged when already disturbing and complicated ideas like patriotism, Christianity, even migration, become muscular–I despise attaching that modifier, but it has become not merely popular but dangerously descriptive.

It’s also interesting how evangelical conservatives like Cameron want to keep putting the muscular foot forward when, as Todd Brenneman has shown in his fascinating book, Homespun Gospel, sentimentality seems to pervade the entire evangelical Christian body.

http://usreligion.blogspot.com/2014/05/the-homespun-gospel-or-does-mark.html