Friedrich Nietzsche demands a certain amount of deference. Or so it seems to me. Whatever you might say about him, it’s rather frowned upon to dismiss him or actively dislike him. And it is not that hard to understand why. The dude was a genius, right?

But not just any kind of genius, but that kind of genius scholars like best – the complicated, complex, self-contradictory kind. The Rorschach test kind. The kind of genius that said a thousand short, sharp little things about the world of the present and the world of the past that come through with such perfect analytical clarity – and yet, put them all together and what you get is messy, unclear something-for-everyone. (A thinker for all and none!, he might have said.) Which means, of course, that everyone gets to play the analytical game of Who Is Nietzsche? – indeed, being a contestant is so popular we can now even write entire books not ourselves partaking in the game, but documenting and explaining how everyone else has played it.

Despite all the varying interpretations, however, a general trend holds true: whatever Nietzsche was, he is not easy to categorize politically. In fact, it seems that it is precisely because of all these different Nietzsches that the only consensus that can be manufactured out of this diversity is that Nietzsche must be regarded, in some sense, as uncategorizable. Nietzsche is obviously not a socialist, nor a leftist in any conventional sense, nor certainly not a liberal, and, of course, Nietzsche is not a conservative.

Or is he? Looking back on my own personal encounters with Nietzsche, it is starting to seem strange how off-the-table this take on Nietzsche has always seemed. In college, where I first came to know Nietzsche beyond a vague impression, he was not presented in the context of a discussion about conservatism. And as I went on to encounter him in graduate school, he almost never came packaged as a conservative. On the contrary, for me he has been presented much more often as a figure that conservatives are rather terrified of.

Take, for example, Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen’s recent book, American Nietzsche. Ratner-Rosenhagen does discuss the admiration some figures with right-leaning inclinations had for Nietzsche; I finally discovered, for instance, why conservatives are so into H.L. Mencken. But many more pages are spent both on discussing how various socialists and anarchists were inspired by Nietzsche, and how various types of conservatives – from the religiously inclined to the eccentric Allan Bloom – viewed him as a threat that had to be vanquished. And I remember, while reading the extended discussion of leftists’ relationships with Nietzsche, waiting to hear about how they squared their love for him with his obvious, and extensive, disdain for socialism or an egalitarian conception of politics. But this discussion never came.

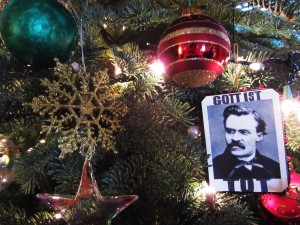

Let me be clear – I’m not suggesting that it wasn’t there because of a large oversight on Ratner-Rosenhagen’s part. On the contrary, I suspect it wasn’t there because it wasn’t there; ie, it never materialized in her sources as a major theme of her American Nietzsche. What I am suggesting, however, is this: isn’t this weird? Wouldn’t we expect a man who decried how altruism, egalitarianism, and democracy drained Western civilization of all its brave and daring beauty to be a little bit more present in the annals of conservative thought? Where is the deep, rich history of conservatives – of the non-theological variety, of course – setting up societies to emulate and bring about the era of the uber-masculine overman? Could they have asked for a more attractive, brilliant, imposing figure to adorn their ideological altar?

Of course, there is the ease with which, starting with the editing wiles of his sister, Nietzsche was packaged for ideological use by the Nazis. Yet any scholar worth their salt knows that there is no clear line linking Nietzsche and the Nazis. So the conversation about that connection, it usually seems, comes to an end with its debunking.

All of this explains why I was surprised when I read the introduction to Corey Robin’s The Reactionary Mind. For behold, there in the opening stanzas, was an easy, breezy, nearly afterthought identification of Nietzsche with conservatism. As he wrote, summarizing the argument of his book, “I seat philosophers, statesmen, slaveholders, scribblers, Catholics, fascists, evangelicals, businessmen, racists and hacks at the same table: Hobbes next to Hayek, Burke across from Palin, Nietzsche in between Ayn Rand and Antonin Scalia, with Adams, Calhoun, Oakeshott….”[1] (the list goes on).

“Whaaat?” I remember thinking (and, in my imaginative retelling, I’m cocking my head like a dog). “That’s unusual. Refreshing, however.” Robin went on to discuss Nietzsche a little further in The Reactionary Mind, but only through his influence – claimed by her to be nonexistent but clearly quite significant – on Ayn Rand. Although Robin described Rand’s incorporation of Friedrich as a kind of “vulgar Nietzscheanism,” he also noted that the profile of one of her aborted literary characters, a murderer of a young girl, was “not a bad description of Nietzsche’s master class in The Genealogy of Morals.”[2]

Then in the spring of 2013, Robin published an article that elaborated on some of his thoughts about the relationship between Nietzsche and the right – and in this case, particularly the neoliberal politics of the Austrian school. The pushback was not only considerable in its intensity, but in its breadth. There were very few people it appeared to please. On the one hand, many liberals and leftists didn’t see the connection, or thought it too tenuous. Even more compellingly however, conservatives – especially libertarians – strenuously resisted the association of their intellectual heritage with Nietzsche. The response then, in broad strokes, seemed to be this: those on the left didn’t want their Nietzsche tarnished, and those on the right didn’t want him at all.

This response puzzled me. It was not only that I was, apparently, amongst the few that found Robin’s case pretty compelling. It was also the way in which I sensed some kind of deep resistance to treating Nietzsche in this way; to clearly connecting him to developments in political thought in even the roundabout manner of pointing out “elective affinities.” This is not how academics usually handle Nietzsche, who is presented first and foremost, in most cases, as an existentialist: he is there to guide us, to help us through our own questions, but not to whisper any answers in our ear. Or, as Ratner-Rosenhagen puts it, “encounters with Nietzsche’s philosophy and persona provided an opportunity for observers to examine their ideas about truth and values in a world without foundations.”[3] And Nietzsche, after all, was trying to transcend all values, right? So to label him – or even simply associate him – with this politics or another must be deeply flawed. He was indeed a radical of sorts, but not of any kind that we can fairly categorize.

But I wonder if the predominance of an ambiguous, or even apolitical Nietzsche is due at least in part to the monopoly scholars have enjoyed in interpreting him. For until recently, academics have argued primarily with other academics over which Nietzsche is the correct Nietzsche. And among academics, the argument that Nietzsche can be read as a conservative has been uncommon ever since he was rescued from being a Nazi. Therefore, the argument hasn’t been handled in part due to it rarely being made.

And as a consequence, this interpretation of Nietzsche as anything but conservative falls most heavily on the heads of those lacking academic capital. On the more lighthearted side of this dynamic is the stereotype of the young, alienated young man who gravitates towards Nietzsche for guidance. After all, who can recall that scene in Little Miss Sunshine – “Is that Nietzsche? You don’t speak because of Friedrich Nietzsche?” – and not smile? Yet sometimes such sentiments turn dark, and we end up with a case like Jared Lee Loughner, who credited Nietzsche with inspiring him to open fire on Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and several of her supports as they left a campaign event.

When such reports hit the press, popular media outlets are flooded with essays from scholars explaining why it is a mistake to associate such atrocious acts with the thinking of Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche, they decry, has got to be the most misunderstood genius that ever put pen to paper. You sense the frustration coming through in these defenses, and in some cases, scholars defending Nietzsche against vulgar Nietzscheanism slip into participating in some crude stereotyping of their own. Angry, horny, narcissistic young men – who think they are much more clever than they actually are – are the sort of people that will chronically misinterpret Nietzsche. It requires, in short, that you’re already pretty much a monster for Friedrich to have this effect on you. True, some of his writing does lend itself to this interpretation – but any close, thoughtful reading will reveal it to be exactly the opposite of the message you were supposed to receive.

Let me take a moment here to clarify what I’m hinting at. I’m not implying the opposite of what these defenses of Nietzsche suggest – I’m not arguing, in short, that the “true” Nietzsche is a straightforward guidebook to sociopathy. Nor am I suggesting that the line between murderous intentions and “conservatism” as such is clear-cut, although I would be hard pressed to deny that contemporary conservatives often seem to fetishize violence.

But what I am implying is that it might do well for us to reconsider why we so easily dismiss the not terribly unusual cases of individual readers picking up on the darker edges of Nietzsche – the Nietzsche that seems to celebrate violent self-expression that takes not the time to pity its victims, the Nietzsche that despises democratic culture and egalitarianism as the herd morality of slaves, the Nietzsche that promotes misogyny. For if there is one thing encountering Nietzsche should remind us, it is that the line between author and reader, between intent and result, is not always as clear as it seems.

Consider Ratner-Rosenhagen’s reflection, for example, that Nietzsche’s admirers “used the philosopher’s terms and aspects of his life to describe themselves to themselves. And yet the varieties of the selves fashioned suggest that the distinctions between reception and production, and between readership and authorship, are blurry at best.” The conclusion she draws from this confusion is that the diversity of “Nietzsches” readers created suggest just how tenuous the link between the intent behind a text and the actuality of their impact can be; or, in other words, “Despite the readers’ sense that Nietzsche happened to them, we do better to see how they happened to Nietzsche.”[4]

Yet notice how interpretations of Nietzsche are thus taken to say something about his admirers, but drastically less about Nietzsche himself. It seems to me, in other words, that it is not so much that the distinctions between reception and production are being blurred so much as reception is being declared as an irrelevant place to look for the real historical significance of ideas. The reception of any given thinker, of course, is historically relevant as long as it is clear that the topic is her reception and not the actual meaning of her words – but given any amount of complexity in reception, it is unsound to suggest that a study of receptions can also reflect back on how we asses the author herself. Ratner-Rosenhagen declares as much in the opening of her book, clarifying that it is “neither a hagiography of, nor a screed about, Nietzsche. It is not even a book about Nietzsche. It is a story about his crucial role in the ever-dynamic remaking of modern American thought.”[5]

Such a sharply conceived project is, of course, the model of a well-designed scholarly research project. And yet, I can’t shake the feeling that there is something very odd about this move, which seems rooted in an inclination I’ve discussed before – the desire to study and evaluate ideas independently from their observed consequences. While at times this approach seems appropriate, at others it begins to border on antisocial – a word I use with its political connotations. For does it make sense to segregate the evaluation of a thinker from the impact of her thoughts? Should we not hold Nietzsche responsible for some of the more overtly elitist, anti-democratic, and sexist ideas he advocated and, not surprisingly, others thus read him as advocating? If so, perhaps classing Nietzsche as some kind of conservative – and thus holding his feet to the fire of his political pronouncements – is one way of doing so.

One of the most common objections to such an approach, of course, is that it does violence to the work of a thinker by neglecting or altogether ignoring original intent (usually to be understood in the context of her historical moment). That’s certainly what scholars of Nietzsche routinely say when called upon to reckon with his fascist, objectivist, or violent admirers; indeed, it is as though they feel the tragedy of their thoughts and actions are compounded by their having to drag down poor Friedrich with them, where he clearly doesn’t belong.

But whether they may be right or wrong, consider how such logic would fare in any other situation. An architect constructs a building and, either out of laziness or some kind of self-satisfying blindness, creates a beautiful but sadly not functional structure. It collapses and kills dozens of people. At this point, when the public looks to hold the architect responsible, no one considers arguing that because it was not her intent to kill people with her design, we should, therefore, not factor their deaths into evaluating her work. We would, certainly, consider it much less of a crime than had she done it on purpose, at which point she would experience a permanent form of social death. But nonetheless, in such circumstances questions of intent are regarded to only have limited relevance in determining the social value of someone’s actions.

It is not clear to me why a similar logic does not hold for the authors of ideas. Perhaps it has something to do with the relationship between the perspective of individualism and its corresponding nightmare, oppressive social censorship. We protect the integrity of Nietzsche’s project as he intended it to be expressed, and, in turn, view the Jared Lee Loughners of the world not as social products enmeshed in and influenced by the ideas they encounter, but as singularly sick people. We isolate their interpretations, in other words, from the memory of Nietzsche; or at the least, attempt to contain those negative associations with assertions of expertise and scholarly authority. This is not what Nieztsche really is, we want to believe, because it is not who we say he is. This has to be so, for if the value of ideas rests not only in the way they create new possibilities for ways of being for individuals, but also must be evaluated according to their practical impact on our larger social existence, well, then, how can we keep such a project from getting out of control? Who decides what has good or bad social consequences, and aren’t we just setting ourselves up for some kind of perpetual, low-level McCarthyism? (Or worse?)

These are good questions, and ones I can’t answer comprehensively. And, moreover, any attempt to evaluate ideas socially – which is to say, to consider their impact as just as important as their intent – will run into a host of problems. Nietzsche is a prime example of this, for it is precisely that his impact seems so diverse that any attempt to categorize him would seem to run afoul of contradictory evidence.

And yet – and yet there are still the words on the page, advocating at the least an embrace of some

kind of elitism, and at the worst a violent one at that. And although we all know what a wreck Nietzsche’s sister made of his work, there have been many texts much more difficult to package for Nazi consumption than his. I am also not willing to imagine that the interpretations of Leopold and Loeb, Ayn Rand and Jared Lee Loughner, have nothing to little to tell us about Nietzsche or the value of his ideas. It seems to me that to do so is to indulge in a form of elitist, antisocial idealism, where only those who hold degrees are allowed to decide which evidence counts and possess, moreover, a monopoly on authoritative pronouncements about the social value of ideas.

And so, for myself, it makes sense to consider Nietzsche a conservative – a weird one, a thrilling one, and one I even have thought of in my lifetime as a friend – but, nonetheless, still some kind of conservative.

[1] Corey Robin, The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 34.

[2] Robin, The Reactionary Mind, 90, 91.

[3] Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and His Ideas (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 24.

[4] Ratner-Rosenhagen, American Nietzsche,

207.

[5] Ratner-Rosenhagen, American Nietzsche, 27.

23 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

An initial reaction to this thoughtful post:

I don’t think Nietzsche should be held responsible for Nazism, and I don’t think Marx should be held responsible for Stalinism (or Leninism or Maoism, for that matter). But I do think a comprehensive ‘evaluation’ of any influential thinker has to treat his or her ‘reception’ as something more than simple misinterpretation — as something more like selective appropriation.

In the case of Marx, it’s very possible to make the argument — and I might well agree with it, in fact I do agree with it — that Marx was fundamentally a democrat (small “d”) and that authoritarians who have used his name have perverted his thought. At the same time, one probably has to acknowledge that there are aspects of Marx’s writing that, when selectively used or appropriated, could buttress projects he would have abhorred. I refer to Marx here, not Nietzsche, but the general point presumably holds for any major writer who produced a lot of words in the course of a lifetime.

I’ve never read Nietzsche — one of quite a lot of gaps in my education (such as it was) — but as a student I read James Joll’s survey Europe Since 1870 (Harper & Row, orig. ed. 1973), and here’s a little piece of what Joll (on p.167) has to say about Nietzsche. The fact that this passage is from a very good textbook by an excellent historian rather than a learned treatise on Nietzsche may actually make it of more interest here:

“Any short summary of Nietzsche’s views inevitably does him an injustice. It ignores not only the trenchancy and humorous irony with which he attacked the stuffiness and complacency of late nineteenth-century bourgeois society, but also the poetic insights and the lyrical and gentle aspects of his work…. Yet to stress the violent and even racialist aspects to be found in Nietzsche’s work is nevertheless not entirely unfair. It was his attack on liberal sentimentalism and on a hollow belief in progress that attracted the generation which, all over Europe, seized on his writings around the turn of the century; while his emphasis on the purifying virtues of violence accounts in part for the enthusiasm with which the outbreak of

war [i.e. World War I] was greeted by many intellectuals in nearly all the belligerent countries.”

Joll goes on to note that N’s appeal was broader than “just to fanatical nationalists” and that his anti-bourgeois message appealed to the younger generation and to avant-garde movements of various kinds all over the continent.

I don’t know much of anything about N’s reception in the U.S. (beyond what I’ve read in the post here), but for a short capsulization of N’s reception and significance in Europe, I would think what I’ve just quoted is pretty accurate (albeit no doubt somewhat oversimplified, as even the best surveys almost inevitably are).

Excellent post. Timely, too, since one sense in the air a new Left offensive against Michel Foucault, perhaps the 20th century’s greatest Nietzschean. Recent arguments that Foucault was incliining towards neoliberalism towards the end of his life will no doubt begin to be interwoven with wider-frame considerations of how much that is “bad” in Foucault can be traced back to what is “bad” in Nietzsche’s politics.

For me, “conservatism” indexes visions of the world that stress, above all, the natural-ness of organic unity and relations of authority/subordination, and that ascribe to outside subversion or internal pathology the failure to find joy in one’s place within the family, the city, the nation-state, the religious chain of being, and/or the telos of history. On this level, ruthlessly de-naturalizing all of the above, all the time, seeking out, always, a destructive untimeliness, Nietzsche is not–whatever else he might be––a “conservative.”

I beg to differ. Your reading of Nietzsche as an absolute iconoclast or nihilist would depend on a selective reading of his works. This is precisely what Nietzsche specialists have criticized Foucault and other poststructuralists for. There’s a very clear negative reaction to European modernity in Nietzsche, against the rise of the multitude, the specter of democracy and socialism, the discourse of human rights, etc. And there are clear conservative aspects in his invocation of a “rule of the best,” echoes of the history of “great men” in his work (Goethe as perhaps the greatest man). For example: “[T]he concept of greatness,” he says in the same work, “entails being noble, wanting to be by oneself, being able to be different, standing alone and having to live independently.” (Beyond Good and Evil, 212).

The continuing problem for interpreting Nietzsche then is, as Robin is pointing out in this post, is it possible to harmonize those elements in Nietzsche that suggest a “ruthless denaturalization” of all–my favorite Nietzsche by far–with elements that are clearly normative and prescriptive in his thought.

Hi Kurt – yes, I think you are right that reevaluations of Foucault are relevant in this discussion. I have a sort of playful indecision about Foucault – I’m don’t feel like I’ve thought about him or read him deeply enough to commit, but it does seem that insofar as he doesn’t offer a way out of the politics of the individual, he shares this problem with Nietzsche.

And yeah, if you keep conservatism to a vision of the organic, then Nietzsche won’t make the cut. (Although you wonder about his pronouncements on women.) But I find that definition too limiting, so, along with Robin, I go with a “lumping” category. I’m a lumper!, what can I say :).

“For does it make sense to segregate the evaluation of a thinker from the impact of her thoughts? Should we not hold Nietzsche responsible for some of the more overtly elitist, anti-democratic, and sexist ideas he advocated and, not surprisingly, others thus read him as advocating?”

If the goal if apportioning blame and categorizing in terms of a modern left/right, radical/reactionary set of norms, than your method (if not necessarily your conclusions) might be apt, as it is for a Corey Robin, in search of “the” reactionary mind. But engaging in this kind of evaluation moves you away from the kind of historical and deeply contextual argument that a reception study or a discourse study makes, and tends to a greater decontextualization. Now you are no longer talking about what, say, Walter Kaufmann made of Nietzsche by downplaying the antisemitic elements in his writings, but arguing with him about whether Nietzsche was a proto Nazi or not, which implies that there is a core and singular Nietzsche at the bottom of his oeuvre. There are plenty of people who want to continue that argument (Nietzsche is a radical–he uproots religion, metaphysical, and universalist claims of all kinds; Nietzsche is a reactionary anti-democratic, racialist, romantic longer for aristocratic values). But I think intellectual history might bring a deeper contextualization to the story, one in which questions of what camp does X thinker belong in, can only be got at by asking why a variety of readers have reached such radically different readings of that thinker, and what the conditions that might have contributed to those divergences have been. Instead of thinking that there might be an essential Nietzsche that we can get at through a close and intensive reading of his texts, this method de-essentializes Nietzsche by situating his writings in the contexts of its larger cultural and intellectual sources and the remaking of those writings by his readers and their various cultural needs. The goal is not so much to make moral and ideological judgments (which, of course, have their place in any humanistic understanding) but to aim at a historical understanding. So, I am puzzled why you think this historical method contributes to decontextualizing thinkers, when it seems to me that the method of apportioning blame and fitting a thinker into a pre-existing category of conservative or radical is much more of a decontextualizing move.

Hi Dan — Thanks for the comment, it will allow me to elaborate and clarify a bit!

“But engaging in this kind of evaluation moves you away from the kind of historical and deeply contextual argument that a reception study or a discourse study…So, I am puzzled why you think this historical method contributes to decontextualizing thinkers…”

I don’t; or, not in the sense you are talking about. As I mentioned when I wrote about the goal of discovering original intent (or reception) through contextualization, that’s not my concern here.

I’m not, in this post at least, concerned with taking ideas out of the historical context in which they were either created or received – which, as you point out, varies over time. I’m concerned with studying ideas in isolation from their cumulative effect – over many historical contexts. We can study reception in the most contextualized, de-essentialized way, as we need to; that’s a start. But to end there – to not, as you put it, “make moral and ideological judgments,” about all this knowledge we’ve accumulated is, in my mind, very problematic. It’s the “intellectual history for what?” question again and, as I said in this post, I find it very strange that scholars want to protect their subjects from the consequences of their thoughts simply on the argument that historical context means we can’t hold them responsible.

Which is why you half misunderstand me when you say I am “arguing with him [Kaufman] about whether Nietzsche was a proto Nazi or not.” You’re right that I am arguing about what we should conclude about Nietzsche – but I’m not arguing about who Nietzsche, in his exact historical moment, or within the mysterious confines of his mind actually “was.” And thus I’m not actually essentializing him. What I am saying, is that I care less about who Nietzsche “is” and more about what Nietzsche has *done,* historically. Ie, what are the observed social consequences of his ideas? And then, I’m doing something even a little more unconventional, and saying if we can answer that question, then that should reflect back on our judgment of and classification of the man. Not because he was a “proto-Nazi” in any essentialist sense; I really can’t stress how much I don’t care about figuring out the ‘essence’ of Nietzsche; but because I care more about what ideas *actually do* than what they were intended to do or, what various people thought they did in isolated moments in time. (And not all interpretations, moreover, are equal in terms of consequence; if you take Nietzsche as the existentialist Nietzsche but barely even change your daily routine, that pales in comparison to someone who reads the fascist Nazi and decides to kill people.) To me, this is a history minded approach, but it is a history-minded approach that looks to understand the larger march of the past instead of just specific moments in it, and to try and then go ahead, bite the bullet and make some decisions – because then, it also looks to the future. Which is, of course, why it is overtly political, rather than just implicitly so.

“why a variety of readers have reached such radically different readings of that thinker…”

But this is, of course, the challenge with that project. As you pointed out, Nietzsche has all sorts of “impacts,” that are themselves products of a particular context, so how can we categorize him? What I’m trying to ruffle the feathers of a bit here, though, is that it seems to me there are a lot of good, compelling reasons to place Nietzsche, broadly, in the conservative column; at least enough for it to be in the air as an option many people take seriously. However, scholars seem so resistant to this – contemporary ones, that is – and I think that is odd; it is like the conversation itself makes them squeamy or offended, as the reaction to Corey Robin’s article displayed. And to me, that has something to say about this desire to either study reception only in isolation, rather than as something we look at to tell a larger, even if with-many-plot-turns story, and, again, a resistance to making evaluative judgments of that we study.

Great discussion above, everybody. (and apologies for egregious mis-spellings in my comment above).

Robin, I think it is difficult to classify Nietzsche as conservative since conservatism has been difficult for historians to define outside very specific context. You apparently have a well defined idea in your mind. What we can do is think of singular or complex of ideas that Nietzsche espoused and see both the antecedents and their subsequent influence. I think we would find both the left and right of the political spectrum taking up some portion of his thought. The process of trying to categorize him is rather misguided, I believe. I am with Dan on this.

Dan writes: “If the goal if apportioning blame and categorizing in terms of a modern left/right, radical/reactionary set of norms, than your method (if not necessarily your conclusions) might be apt, as it is for a Corey Robin, in search of “the” reactionary mind. But engaging in this kind of evaluation moves you away from the kind of historical and deeply contextual argument…”

Sigh. I think I’ll just outsource my response to Alex Gourevitch, who dealt with this same charge when it was leveled by Mark Lilla three years ago:

‘…the aim of Robin’s book is to connect an account of the essence of conservatism to the obvious fact of its historical variation. That is why the book is mostly composed of a series of chapters examining concrete, historical examples — Hobbes, Burke, Rand, neoconservatism. The organizing assumption of these chapters is that conservatism revolves around a political principle that is consistent yet adaptive, an idea that is sensitive to context and capable of producing a wide array of concrete, if conflicting, prescriptions….

‘That conservatism is reaction makes it no less principled. Rather, reaction is inscribed in the political principle itself. But as reaction conservatism will assume a variety of forms depending on the particular struggle it is mobilizing against: “If conservatism is a specific reaction to a specific movement of emancipation, it stands to reason that each reaction will bear the traces of the movement it opposes. . . . Not only has the right reacted against the left, but in the course of conducting its reaction, it also has consistently borrowed from the left. As the movements of the left change — from the French Revolution to abolition to the right to vote to the right to organize to the Bolshevik Revolution to the struggles for black freedom and women’s liberation — so do the reactions of the right.”

‘This historical adaptability and sensitivity to context is a theme Robin repeatedly comes back to throughout his book: “[Conservatives] read situations and circumstances . . . their preferred mode is adaptation and intimation rather than assertion and declamation . . . the conservative mind is extraordinarily supple, alert to changes in context . . . the conservative possesses a tactical virtuosity few can match.”

‘I have supplied so many quotes from the book to drive home the point that Robin is well aware of the problem of oversimplification and caricature. Rather than shy away from the challenge in the name of complexity and nuance, Robin rises to it. Here at once is an argument about what unifies conservatism — the rejection of equal freedom — and what accounts for its many diverse modes of expression: the reactionary, and thus context-dependent, mode in which conservative politics is carried out. Since every particular struggle for equal freedom bears the marks of its moment and its society, conservatism too modulates itself in response to the needs of time and place.’

I recognize this is Robin’s thread, so I don’t want to hijack it with a discussion of my work. But if there’s going to be a discussion of my work, it would be nice if it were actually a discussion of, you know, my work.

Let me deal with Robin’s response first, and then Corey’s in another comment.

I understand that you want to move away from a form of contextualism that emphasizes original intent, and I’m all for that. But you conflate original intent and reception studies as if they are two sides of the same coin, each equally absolving thinkers of the historical consequences of their thought. I think discourse studies and reception studies are the opposite of studies that emphasize authorial intention; they contextualize by emphasizing the ways in which meaning is quite independent of authorial intention. The purpose of limning “context” is not to try to explain original intention, but to understand collective patterns and diversity of meanings. But you seem to have a bone to pick with this method of contextualism, primarily it seems to me, because it evades the attribution of responsibility to authors for the consequences of their actions. So your preferred method of contextualism, if I read you correctly, is consequentialist. But this brand of consequentialism I read as a form of essentialism. In order to say that X’s thought produced Y, it seems to me that you have to believe that there was something necessary in X that led to Y, that Y is not an arbitrary outcome produced by a number of other contextual factors that simply glommed on to something that was in the language of X. What does it mean to speak of the consequences of Nietzsche’s thought? Here you suggest that Jared Lee Loughner or, I suppose, Leopold and Loeb, not to mention H.L. Mencken or a variety of antisemitic and antidemocratic thinkers were not just interpreters of Nietzsche, but somehow consequences of his thought, that they were compelled to become what they were by the force of having read Nietzsche. This implies that there is something in Nietzsche–some core aspect of his writing and thinking–that produced these outcomes. But then, when other outcomes that you perhaps find more anodyne are produced–the Kaufmann’s, Bourne’s, Lippmann’s–the existentialist, the radical critics of religion and all existing hierarchies, the Death of God theologians, these are seen as somehow not the consequences you are looking for–which implies that the real consequences must be the reactionary ones of National Socialists, worshippers of therapeutic violence, and crushers of movements toward greater egalitarianism. None of these thinkers are expressing the original intent of Nietzsche; I don’t think there are any ways to distinguish between which are the consequences these ideas necessarily produce unless you believe there is something essential in the writings that produce the negative consequences, in which case all the other readers and interpreters of Nietzsche are mistaken. You say:

“And not all interpretations, moreover, are equal in terms of consequence; if you take Nietzsche as the existentialist Nietzsche but barely even change your daily routine, that pales in comparison to someone who reads the fascist Nazi and decides to kill people.”

This kind of argument is equivalent to saying that Stalinism is the consequence of Marx, because frankly Stalin’s application of Marx was a great deal more consequential than, say, that of Western Marxists or advocates of social democracy. My point here is not to absolve Marx of the crimes of Stalin (nor to attribute them to him), but just to suggest that the traditions of Marxist thought have produced diverse outcomes that can not be accounted for by trying to apportion responsibility to Marx or to engage in an argument about which was the real consequence of Marx’s thinking.

When you talk about what ideas *do* in the world, you seem to be suggesting that you can clearly identify the outcome and consequence of a body of thought in a pretty clear and direct way. I can’t see how this is not a form of essentialist thinking, even as it is dressed up in pragmatist clothing.

Corey–

Although my mention of your book was really just a response to Robin, who had pointed to it, I’m a little surprised that it provoked your response in this way. I wasn’t suggesting that you didn’t analyze or recognize the variety of historical circumstances or conditions to which your reactionaries/conservatives were responding, nor the ways in which they drew on historically specific movements critical of existing hierarchies and dedicated to emancipationist and egalitarian projects to fashion their own critical response. But it seems to me that your goal in that book is to find a style or mode of thinking, a sensibility or a form of “metaphysical pathos” that unifies the variety of thinkers you examine, to see in them a united frame of mind or way of thinking. Your book, in my reading, is not a history of conservative thought in the sense of trying to show how a distinct body of thought was shaped as a tradition, but rather a portrait and analysis of a mode and style of thinking that you find in thinkers from Burke and de Maistre through Rand and contemporary movement conservatives. In other words, your intentions are not primarily historical (e.g. situating nineteenth-century conservatives in nineteenth-century contexts), but an attempt to show that conservative thought throughout its modern history has embodied a consistent set of orientations toward the emancipationist movements it has been dependent upon and reactive to. Which is why the chapters take the form of topical essays, rather than a comprehensive and chronologically guided narrative. Your goal, as I read it, is primarily categorical–concerned with showing the common outlines of a conservative intellectual orientation. At the risk of turning Robin’s thread into a discussion of your book, which I wasn’t really intending and only mentioned in passing, do you think I’m wrong in this characterization?

Two thoughts.

First, I was reacting in part to your “apportioning blame.” I don’t really understand what that means — blame for what? — but insofar as it’s meant to suggest there’s a moralizing drive to say these are the good guys, these are the bad guys, I think that has very little to do with my work. As I’ve said in a different context, I feel like there are lot of folks out there who have a very strong and unresolved moralistic streak which leads them, when they’re reading other’s people work, to ascribe all sorts of moralism to it that’s not really there. I’m not saying that’s what’s going on in this instance, but it is, I feel, how I’m often read, which has little to do with me or my intentions.

But second, I reject the premises of your claim: namely, there that is something mutually exclusive about finding some persistent orientation and understanding in a deeply contextual way what is going on at any given moment. And it’s in part the almost reflexive way in which historians posit these two approaches as antithetical that has, of late, made me so wary of contextualism and historicism.

My goal in writing the book was to give scholars of way of understanding in any given context what actually is going on with a text that I call conservative. In a way — that almost amuses me — my entire approach was inspired by Skinner, who was one of the first to turn me onto the polemical nature of political theory and political argument. That was the whole point of his early programmatic essays: understand what a political theorist is *doing* in writing political theory, understand what/whom s/he’s trying to achieve in writing a text — similar to what s/he might be trying to achieve in political action itself. Skinner understood political theory as a mode of political action, which in part meant understanding political theory as conflictual and agonistic, as a mode of action against something. I tried to provide a framework for how scholars might think about what conservatives in any given context are actually acting/arguing against. That way we might be able to understand the specific moves and counter-moves of their arguments. And that it was only by comparing those moves and counter-moves across time, that you would begin to understand the specificity of those moves and counter-moves within their own times. In other words, it was my contention that in order to understand the moves and counter-moves, it wasn’t enough just to look at the local context; you had to see the consistency across contexts. Otherwise you’d never actually see the specificity within the context itself.

I recognize that my approach departs from some of Skinner’s methodological strictures, but I think it’s ultimately in keeping with the spirit of his approach. But b/c the book departs from the over format and methodology of a strict contextualism (though not always), historians think it’s not historical.

Because you’ve all decided what it means to think historically — methodologically speaking (i.e., gather every last pamphlet that was written, write a micro-study of the conditions of its utterances, and whatever you do, when you’re writing about the pamphlet, don’t look or think beyond the immediate month that it was written; I exaggerate, I know) — in a way that I think is actually blind, at least in the case of conservatism, to history itself.

So just to give a quick concrete example of what I’m talking about: upthread or downthread, someone says conservatism is about naturalizing social relationships, so therefore Nietzsche’s not conservative. Well, that’s true of some conservatives, depending on their context, but not others (with the exception of the family, for example, Nozick doesn’t naturalize social relationships at all; and of course at various times Nietzsche most certainly did naturalize some social relationships.) Likewise, some leftists naturalize social relationships. So to my mind that’s not going to take you very far. But it’s only by comparing these moves/counter-moves of conservatives that I describe above — across time — that you’ll begin to see those moves as moves. Why certain moves can never be made, no matter what the context is, and why other moves appear as moves. In other words, to understand the moves in the game, which is Skinner’s whole point, you have to understand the game. But to understand the game, you have to examine how it’s played in multiple contexts, not just one.

A quick response. The “apportioning blame” was in reference to Robin’s desire to find moral responsibility for the consequences of a particular thinker, and not in reference to your book. The latter was mentioned only because she had invoked it, and I saw it as sharing the categorical impulse. Sorry about any ambiguity there.

Second, we’re not as far off as you might imagine, and I share some of your concerns, as my other writings might indicate, with history that commits itself only to very narrow contextualizations and foregoes larger comparative frameworks. I will only say here that the concept of “context” is severely under-analyzed by historians and that there are multiple contexts–all of which are question- or problem- dependent–for any historical phenomenon. And the relevance of context, as you suggest, can only be understood by some kind of larger comparative frame.

Hi Dan – we’re boiling things down to irreconcilable differences, but I think the differences here hinge on what our mutual projects are, and a difference in temperament about how brave (or is it brazen?) we ought to be in drawing conclusions. First, a small clarification:

“But you conflate original intent and reception studies as if they are two sides of the same coin, each equally absolving thinkers of the historical consequences of their thought.”

Well in this case I have discussed how the search for original intent and the work on reception have produced similar results; but this by no means has to always be the case.

“In order to say that X’s thought produced Y, it seems to me that you have to believe that there was something necessary in X that led to Y, that Y is not an arbitrary outcome produced by a number of other contextual factors that simply glommed on to something that was in the language of X.”

I’m glad you picked up on this. I agree that the result of X is largely dependent on context – that X did not “necessarily” have to lead to Y in any and all contexts. But here’s the thing; in history, we know what the context was! And yes, the context changes over time; but these changes are not unrelated to one another, nor, in reception history with any modest time boundaries, do they take place in radically different times and places. So when I say, we can conclude something about X based on results, I am not referring to an essence of X that could and would always leads to Y, but how it has played in this society or that one. So, in the history of say, capitalistic societies shaped mostly by Western culture, we can say X tends to play a certain way (or stands a good enough chance of playing in such a way that we would do well to avoid it or embrace it). So I’m interested in how it has played in the longue-duree, so to speak, of *this society,* of *this history* – because, for the most part, this is the one we’re still in! In this sense, I obligated to be bounded by what actually happened, and is still happening.

Which brings us to this fundamental difference:

“My point here is not to absolve Marx of the crimes of Stalin (nor to attribute them to him), but just to suggest that the traditions of Marxist thought have produced diverse outcomes that can not be accounted for by trying to apportion responsibility to Marx or to engage in an argument about which was the real consequence of Marx’s thinking.”

I disagree; I actually think “an argument about which was the real consequence of Marx’s thinking” is exactly the argument we should be having! – with a slight twist. I agree that Marxist thought has produced diverse outcomes – obviously – so when you look at those outcomes, the question you actually have to ask yourself, if you are socially minded, is not which was the “real” consequence – because in a sense they are all equally real – but, considering all the diversity of evidence, what is my best guess as to what is the most *likely* consequence of this idea in this day and age?, in my society? Should I advocate for this? Or should I not? Can I advocate for it with qualifications?, or go full-steam ahead? Can I take some aspect of this and turn it into something new?, or use it as a wedge to transform something else? Or not? – will it just produce the same-old or some terrifying new monster? You end up with, in sum, Gramscian questions. And these are questions that someone thinking towards the future, as I said, asks.

So now, when I go ahead and take a guess – take a position on what these ideas can or can’t do in this world, and take this position based mostly on a body of evidence in the past that was diverse – a lot of people think I’m doing more than I can with that evidence. That is what I gather from this:

“When you talk about what ideas *do* in the world, you seem to be suggesting that you can clearly identify the outcome and consequence of a body of thought in a pretty clear and direct way. I can’t see how this is not a form of essentialist thinking, even as it is dressed up in pragmatist clothing.”

No; I don’t think the outcomes and consequences are either clear or direct (most of the time). Often times it is far, far from obvious and rather obscured! But in the end of the day, I *do* take a guess – I make up my mind, for the moment at least. I used to think Nietzsche could never be regarded as a conservative; now I do. Maybe one day I’ll change my mind again. But I don’t think to come to a conclusion about the value and potential of something in a given context is the same as thinking it is all neat and tidy. Because what isn’t this way? We all make hard calls all the time with limited and contradictory evidence. But unless we only want to understand, and not to build or act through ideas, I don’t think we do ourselves any favors by putting off this task. We may appear more humble, it’s true – but the arrogance doesn’t lie in making up your mind, but considering it fixed and unchangeable from that point onward.

I mean, as an agnostic atheist, I’m also an agnostic everything-else; I don’t know, but I’m going to take a leap and take a guess – because unless we can have the arguments about whether certain ideas will help us or hurt us, in this context we are still stuck in; well, then no politics at all are possible.

There are some interesting questions here about causality, in relationship to authorial intention. In literary studies, the proclamation of the death of the author has dissipated as we utilize and mix different approaches to the object of study that take into account the author as a figure–both symbolic and material. So we now see a resurgence of genetic criticism–looking at manuscripts, etc. to trace how a text comes to be–and philology, even as we are still suspicious of intention as a concept. Intention calls forth the idealist construct of a rational, unitary self, whose ideas are reflected on the text, whose will shapes the form and content of the text. For me, talking about intention is a dead end, unless we approach it as a historically specific construct.

In regards to Nietzsche, it is evident just from the comments that there are no definite answers to the questions Robin Marie is posing here. Which is fine. The slipperiness of Nietzsche’s thought is in my view due to the fact that it is modeled much more as a form of critique than as a structured framework of positive ideas. In this lies its formidable power or as Kurt suggests, the untimeliness of his thought. This is why we have seen so many different forms of appropriations, Nietzsche has been resignified into a multitude of Nietzsches. Most of the appeal–if it is possible to separate affective attraction from intellectual curiosity–can also be attributed to Nietzsche’s modernism: he fits into a mold of late-nineteenth-century intellectual production in both sides of the Atlantic that sought to subvert the conventions of bourgeois culture.

Hi Robin–

Thanks for your reply–this is, I think, a very interesting and productive discussion. I do think you’re moving the goalposts a little.

First you say you’re interested in the specific consequences as they play out in specific contexts, and that is what enables you to make judgements about the responsibility of a particular thinker for the consequences of his or her thought. Then it turns out that you collapse all those specific contexts into the far more general context of capitalist society in the long duree, and essentially say that what happened in the late nineteenth or mid-twentieth century remains a model for understanding an idea’s consequences since the society we live in is fundamentally the same. All of a sudden, context– except in the most general sense–goes out the window! If I say that the conditions that produced the National Socialist interpretation of Nietzsche in the 1930s and 40s are fundamentally different from those we see in the United States today (or in the 30s and 40s for that matter), you pivot away from the specific to a far more general category of capitalist modernity.

Second, I think you evaded my question about Marx and Stalinism, which I raised primarily because you wanted to hierarchically estimate the significance of the consequences of thinkers–suggesting that the greater the social consequence of an action, the more it should be seen as the outcome of a thinker who should be held responsible for it–the existentialist Nietzsche, you said, made little impact and was therefore not as significant in evaluating Nietzsche’s historical consequences as the murderous reactionary. I have said that the work Nietzsche had done in the world is diverse, but you have discounted the versions of Nietzsche that are more in line with left and radical politics, because they have been less consequential in terms of the social effects they have produced. But if we use that same criteria for evaluating the consequence of Marx’s thought, surely we should come to the solution that Stalinism is the significant consequence of Marx, since the social consequences are far more important than other interpretations of Marx (say, as a guide to literary and cultural interpretation). I don’t think you want to do that (correct me if I’m wrong), so you change the topic to whether or not we can discuss and evaluate the differing outcomes of Marx’s thought and make judgments about which Marx was responsible for, but avoiding the conclusion that by the criteria you use to judge Nietzsche, Marx should be “held responsible” for Stalin.

I have no interest in absolving Nietzsche of the crimes done in his name, but by the same token, I have no interest in holding him responsible for them. Mine is not a defensive brief in favor of protecting Nietzsche from his “wrong-headed” interpreters. I’m more interested in the historical question of how ideas are made and remade, and what the limits of that remaking or reinterpretation might be. The political lesson, if there be such a thing, that is produced by the kind of approach to history that I’m advocating is one that says something more like “tread lightly–we know that ideas can have multifarious outcomes, and the intellectual conditions of the world we live in are constantly changing. There is no certainty about where these ideas might take us, except the ironic one that they surely will not be controlled and contained by our intentions.”

I don’t know if this is helpful–but I am compelled to quote a few lines from my favorite recent book on Nietzsche (it is also one of my favorite recent books, period): Alenka Zupancic’s Shortest Shadow.

“At many points, the reading of Nietzsche’s texts is—or should be—accompanied by an affect of astonishment. This is all the more true if we are not looking, in his writings, for some extraordinary opinions that could help us to form or support our own Weltanschauung— that is to say, precisely, if we do not consider these extraordinary statements as opinions.

To read things like “Dante: or the hyena which poetizes on graves,”“George Sand: or the milch cow with the ‘fine style,’” or to have Kant described as the “typical idiot” (not to mention the even more notorious “idiot on the cross”), can indeed produce an amazement, a kind of jolt—this being one of the fundamental elements that makes Nietzsche Nietzsche.

One should stress, however, that Nietzsche knew how to administer such “jolts” selectively and sparingly, in the right amounts; they are not all that numerous.

It is amazing, nonetheless, how little amazement shocking statements like these arouse in contemporary academics (and their writings on Nietzsche).

At first sight, it might seem that this is because, in our postmodern condition, nothing can shock us any longer: we have either habituated or numbed ourselves to practically everything.

Moreover, Nietzsche’s “style” is recognized and valued as an essential point of his revolution in philosophy—everybody agrees on that.

Therefore, it seems to go without saying that he should be allowed to enjoy the privilege of a certain degree of poetic license.

Yet one simple question should be enough to draw our attention to the fact that there is something rather fishy in this attitude: Why is it absolutely unimaginable (among contemporary Nietzscheans themselves) that someone would use this kind of “style” and write, for instance, “XY, the well-known professor of cultural studies, is a fat cow with a fine style”?

One should stress, however, that Nietzsche knew how to administer such “jolts” selectively and sparingly, in the right amounts; they are not all that numerous.

It is amazing, nonetheless, how little amazement shocking statements like these arouse in contemporary academics (and their writings on Nietzsche).

At first sight, it might seem that this is because, in our postmodern condition, nothing can shock us any longer: we have either habituated or numbed ourselves to practically everything.

Moreover, Nietzsche’s “style” is recognized and valued as an essential point of his revolution in philosophy—everybody agrees on that.

Therefore, it seems to go without saying that he should be allowed to enjoy the privilege of a certain degree of poetic license.

Yet one simple question should be enough to draw our attention to the fact that there is something rather fishy in this attitude: Why is it absolutely unimaginable (among contemporary Nietzscheans themselves) that someone would use this kind of “style” and write, for instance, “XY, the well-known professor of cultural studies, is a fat cow with a fine style”?

This is absolutely forbidden, and there is no poetic license that could make it acceptable to present-day academia. If Nietzsche’s style is esteemed within academia, it is in no way accepted by it. Its “jolts” are either swept under the carpet or treated as curious, rather exotic objects.

This is absolutely forbidden, and there is no poetic license that could make it acceptable to present-day academia. If Nietzsche’s style is esteemed within academia, it is in no way accepted by it. Its “jolts” are either swept under the carpet or treated as curious, rather exotic objects…

Does this indeed indicate that the very naive directness of his style is somehow too embarrassing for our delicate and sophisticated postmodern taste?

Or, to use Nietzsche’s own words, isn’t it as if our “conscience were trained to twitch and feel something like a pang at every ‘No’ and even at a decisive, harsh ‘Yes.’Yes! And No!—that goes against [our] morality”?

The word “embarrassing” should be taken quite literally here, since this is precisely the point: there is probably no other philosopher who, by virtue of his “style,” exposes himself in his work as much as Nietzsche does.

And the pathos of his writings springs precisely from this, rather than from the Wagnerian pathos of heroic mythology; it is the pathos of life.

This is also the source of the comic component of Nietzsche’s style—it arises not from a reflective distance toward life (viewed as if from above, where only the Greatest things matter), but from life reflecting upon itself in an entirely immanent way.”

(Zupancic, The Shortest Shadow: Nietzsche’s Philosophy of the Two, 2003, 2-3).

I include this long quote because I think it gets us at some of the missing terms in the discussion above: affect, style, conceptual personae, irony, shock, pathos–and, importantly, philosophy, in the sense posed by Deleuze and Guattari in their final book: what, exactly, is philosophy?

oops, a little cut and paste doubling. with the possibly meritorious effect of bringing into the conversation another radical philologist (certainly not a conservative): Gertrude Stein.

This is a great quote, and it connects with the conceptualization of Nietzsche as a modernist, not too far from an Oscar Wilde, say. Irony is an element that readers of Nietzsche often forget, which has lead many to read Zarathustra at face value. The aesthetic “jolts”–interruptions!–of Nietzsche have been studied extensively, but mostly from a literary studies perspective. This reminds me: there’s a wonderful book that came out in the 90s, by the French philosopher Camille Dumoulié, on Nietzche and Artaud and the notion of cruelty. Sadly, it isn’t available in English. The Spanish translation, which is what I read, is Nietzsche y Artaud: por una ética de la crueldad.

Hi Dan – well, I don’t know if I am moving the goalpost or if we’re just finally figuring out where it is! But either way it’s been helpful in getting me to think through where I am coming from here.

“First you say you’re interested in the specific consequences as they play out in specific contexts…”

I’m not sure when I said that…if you mean, I said it is important to discuss some of the harmful uses of Nietzsche, and so I brought up some specific examples, then ok. My point was that scholars tend not to think of these examples as highly significant; then I asked why? But as I clarified in my comment, “I’m concerned with [the tendency to] [study] ideas in isolation from their cumulative effect – over many historical contexts.”

Now yes, when I said “historical contexts” what I meant was the varying conditions under the larger context of capitalist modernity. I’m sorry I wasn’t clear from the start on that; I think our different frames of mind made me assume we were. My bad. Because yes, I am more interested in finding patterns over these varying conditions – mini-contexts!, if you will! – then isolating them from one another. Things were *significantly* different in Nazi Germany than they are in the US today; but there are also a lot of similarities. (Increasingly so, depressingly.) So no, we don’t agree that it was *fundamentally* different — and no amount of talking to each other about it is going to change the deeply rooted inclinations and politics that result in either call. Perhaps caring more, or being more compelled by, the similarities makes me a bad historian; I can live with that, as I’ve long felt like a historian with a sociologists’ heart.

But regardless, we do have Nietzsche in both times & places being received as an advocate for an antidemocratic, elitist fantasy of society. My guess is that this similarity in outcome has something – not solely, but something significant – to do with the larger shared context of capitalist modernity & how what Nietzsche wrote can interact with that.

And, in addition to doing much harm – in ways more subtle than I’ve talked about here, by the by – I haven’t personally seen Nietzsche do as much good in a way I find that compelling. It’s not like he has no progressive or good consequences, obviously he has; I’m just not that impressed by them. Thus, I conclude that his overall impact has been to contribute more successfully to a conservative frame of mind (because, an individualist one, but, that is to hint at those more subtle things) and its attendant consequences than a progressive or leftist one. You are free to disagree with any part of that assessment – including my implied assessment of the overall impact of individualism! – but I am all for the exact same challenge being posed, or laid at the feet of, Marx or anyone else.

Which gets us here:

“But if we use that same criteria for evaluating the consequence of Marx’s thought, surely we should come to the solution that Stalinism is the significant consequence of Marx, since the social consequences are far more important than other interpretations of Marx (say, as a guide to literary and cultural interpretation).”

I feel like there is an assumption that I am a Marxist and thus, would want to avoid this problem – I’m not, or, at least, not in any sense that I feel comfortable identifying as one and, moreover, I would at the least say that we absolutely must grapple with Stalinism as *a* hugely historically significant event that involved Marx somehow, obviously, and perhaps he *should* be held responsible – in fact my current inclination is to say he should be, to some degree or another. But I’m also far more impressed with Marx’s contribution to good social consequences – which go far beyond cultural and literary analysis – than I am with Nietzsche’s, so I’m not quite ready yet to make a call about Marx.

Because the question for Marx, of course, is this: will Marx’s ideas, even if we try to be selective with or alter them somehow, in most (varying!) conditions of capitalist modernity usually result – or run a high risk of resulting – in creating or reinforcing something like Stalinism? If the answer is yes, then yes; not only do we hold him responsible for this, but we adjust our assessment of him accordingly.

But I’m sorry, I haven’t personally made up my mind yet about that question – and I’m not going to pretend I have just to appear in a comment thread like I have a fully-formed, theory-of-everything-politics firmly in place with no points of uncertainty, ignorance or holes – rather than the reality, which is that I’m in the process of working things out, like everyone. But I definitely think we ought to be asking it, and one day, I ought to “return with an answer,” as Eran might put it! (Incidentally I’ve sort of been working on that this summer, but you had no way of knowing this.) It would be socially irresponsible not to.

But I do have to think through these things you know! Because they are not, as you pointed out, clear or direct; my conclusions about Marx will not be made simply pointing to various historical events (Exhibition Stalinism! Exhibition Black Panthers!) without knowing anything else about them, and quickly seeing the obvious answer. And they weren’t made that way with Nietzsche either – maybe it looks like it was that simple, because I have hardly explained all my reasons for them, but in a single post I was looking more to raise questions than convince anyone. However I’ve been thinking about this one for a while; 10 years!, all said and told – and I decided, alright, this is what I think I’ve concluded. But I don’t think your concern is so much about whether the evidence justifies my position; it seems more that I’ve decided to evaluate the evidence in the manner I have – i.e., with an eye to consequences — with the end goal in mind I have, and have made a call.

And I get that you’re not into that overall project of Gramscian assessment in service of a political project. But I am!, what can I say. And, while I agree that our outcomes are often not controlled by our intent – which is exactly why we have to reckon with the variety of evidence in front of us, and make the best judgment we can based on *probabilities,* not just what ideas might mean to us or to particular people – for goodness’ sake, we have to try. To me, treading lightly is being willing to step back, or change course, if new evidence – from either the past or present – comes to light. But to step out of asking and trying, however imperfectly, the question of, will this help or hurt?, is, to anyone oriented towards the future, to give up.

At the risk of exhausting everyone, one more important clarification that occurred to me and then I’ll take my leave – when I say we must take the consequences of ideas seriously in our assessment of them & their historical impact, I am *not* saying that the relationship between idea & result is always the same. Sometimes the idea is less important; sometimes more. Sometimes it is more altered by its context; sometimes it reinforces more than challenges it. That is why you do have to the historical work of figuring out those relationships – but at the end of the day, I’m still going ask the cumulative trend/probability question!

Thanks Robin. Incidentally, I wasn’t assuming that you were a Marxist; I just think that anyone on the broad spectrum of the left is familiar with–and rejects–standard right wing attempts to discredit all forms of radical thought by pointing to the Soviet Union as the necessary outcome of Marxist theory. I am a little surprised that you’re open to, in your terms, holding Marx “responsible” for Stalin. I certainly am not, but not because I believe that Stalinism is a “corruption” of some pure Marx that we can go back and recover in its uncorrupted form.

On the larger matter, we can agree to disagree about this–as you suggest, evidence and abstract reason are never going to determine our final commitments. Thanks again for a provocative post and discussion.