This is “Biblical Epic Week” at the blog. Check out the prior entries from Ben Alpers and Andrew Hartman. More will follow from Andy Seal, Ray Haberski, and LD Burnett. And if Biblical Epics aren’t your thing, read the fantastic first posts from our new writers, Robin Marie and Eran Zelnik!

——————————————————————————-

I.

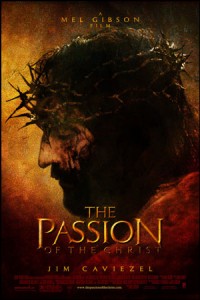

In February of 2004, during the icy depths of a cold Chicago-land winter, I journeyed with some friends to Evanston to see Mel Gibson’s biblical epic, The Passion of the Christ. The film is about many things, but covers, in essence, the last twelve hours of Jesus’ life—with the main points of the film drawn from the four gospels (the first four books of the Bible’s New Testament). I’m pretty sure we saw it during opening weekend. I won’t out my attending friends by name, but let’s just say they were a smart, mix-gendered bunch—familiar with history and Christianity. There were at least six of us—two being Catholic (including me), and 2-4 others were Evangelicals. We knew the buzz, and wanted to see the event first hand. Plus, at the time, the film’s opening was an EVENT.A very Catholic day, Ash Wednesday (Feb. 25, 2004) was selected as the release date. During the prior year, however, Gibson had screened the film for Evangelical audiences. Wikipedia functionally narrates the build-up as follows:

At that point in his career, Mel Gibson—producer and director of The Passion—was a capable, Academy-Award-winning director for a limited genre of popular action films (e.g. Braveheart). He was known as a Catholic, though I don’t think many, at the time of the film’s release, knew of his “traditionalist” bent. By the latter I mean his (and his father’s) purported association with an obscure group of Catholic who believe in “sedevacantism.” Sedevacantism is, briefly, the belief that there has not been a legitimate pope since the death of Pius XII in 1958—because John XXIII and popes following have succumbed to the heresy of theological modernism. Whatever the details of his thinking and theology, in the main we can generally assert that Gibson was, at the time, a practicing Catholic Christian with *some* knowledge of traditional devotions, practices, and theological beliefs. That “some” is a key, but that knowledge explains his interest in producing and directing the film.Prior to the film’s release, Gibson actively reached out to evangelical leaders seeking their support and feedback.[45] With their help, Gibson organized and attended a series of prerelease screenings for evangelical audiences and discussed the making of the film and his personal faith. In June 2003 he screened the film for 800 pastors attending a leadership conference at New Life Church, pastored by Ted Haggard, then president of the National Association of Evangelicals.[46] Gibson gave similar showings at Joel Osteen’s Lakewood Church, Greg Laurie’s Harvest Christian Fellowship, and to 3,600 pastors at a conference at Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church in Lake Forest.[47] From the summer of 2003 to the film’s release in February 2004, portions or rough cuts of the film were shown to over eighty audiences—many of which were evangelical audiences.[48] Gibson received numerous public endorsements from evangelical leaders, including Billy Graham, Robert Schuller, Darrell Bock, and David Neff, editor of Christianity Today.[48] In an open letter published prior to the film’s release, James Dobson, the founder and chairman of Focus on the Family, endorsed the film and defended it against its detractors.[49] Similar public endorsements of the film were received from evangelical leaders Pat Robertson, Rick Warren, Lee Strobel, Jerry Falwell, Max Lucado, Tim LaHaye, and Chuck Colson.[50] [1]

My friends and I knew the film was R-rated.

I had read the previews and knew it contained some intense moments (hence the calls by some reviewers that The Passion be given an NC-17 rating). But I’m pretty sure we were all unprepared for what we witnessed in the theater. One of the most terrible, and most riveting, parts of the film was the scourging. Gibson elected to depict the scourging as performed, in part, with a flagrum (right). Flagrums were designed to rip flesh off the back of the subject. Some flagrums were equipped with a hook to make quicker work of flesh removal. Flagrums were sometimes called flagellum, from which the term flagellation is derived. The act of The Passion during which Jesus is scourged lasted, in the original iteration of the film, almost five minutes. The scourgers switch to the flagrum at the 3:40 mark. Here is the whole scene (never mind the Christian rock sound accompaniment):There is more gore than I remembered. You see and hear the skin ripping (around 4:15). Blood is splattering on the centurion’s laughing face. Blood flows from Jesus’ battered body. It’s not a stretch, I think, to call this Christian torture porn. It feels as if Gibson is attempting to torture viewers into belief, or redemption, through a pornography of suffering. Instead of priestly transubstantiation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ for the community of members, the audience is virtually and individually splattered by a kind of dismembered, disembodied Jesus. This is the portion of that scene, I think, that captured everyone’s attention. And, I’m not sure about this, this may have been the portion removed in 2005 when Gibson released an edited version in the hope of broadening his audience.[2]

II.

What is torture? And what is pornography? These are not trivial questions—nor are the answers as obvious as one might think. For starters, I’m not using those terms in their recent, usual senses. Gibson’s Christian torture is not about waterboarding, rectal feeding, and sleep deprivation, as used by American agents, according to them, to obtain “reliable” information from confirmed terrorists. And when I say ‘porn’ it’s not about erotic films and causing sexual excitement—though some did accuse Gibson of sadism in relation to some scenes in The Passion. To me The Passion is a kind of porn because it’s about an immediate reaction to graphic acts.

My use of the term torture in this analysis includes, of course, the literal torture of Jesus. All the objective, historical sources confirm that a person named Jesus was tortured and killed by Roman authorities at the time. But I also want to invoke the Latin roots of the term torture—meaning from tortura, tortus, and finally torquere: to twist.

I think that Gibson twisted and wrenched the story of The Passion into an epic of bodily strain and torment. Gibson revised the history presented in the gospels to underscore the material at the expense of the Christian spiritual meaning. It’s as if God chose to make a spectacle of his human body to underscore an inhuman, godly ability to absorb punishment. In Gibson’s hands, God becomes a superhero. Gibson’s Jesus ironically becomes inaccessible as a larger-than-life figure that deserves our admiration rather than empathy. The pain endured by Jesus becomes something than turns your head away, in horror. You can’t gaze in empathy at the God-man who has, in theological terms, taken the world’s sin. And if you do continue to view the spectacle, your eyes either glaze over or you become a kind of sadistic admirer of the pain. The Passion, then, reduces The Passion into an uncomfortable and all-too-particular set of choices. There’s no theological payoff of redemption, just a heavy residual of anguish, torment, pain, and voyeurism.

This too, is how it becomes pornography. Pornography, as defined here, is “the depiction of acts in a sensational manner so as to arouse a quick intense emotional reaction.” The film becomes, in the end, a mere sensational and graphic form of “writing” about torture. We are meant only respond emotionally to the violence. The older story of the tragedy of Jesus’ suffering along the Via Dolorosa doesn’t result in any kind of purgation, but only pornographic voyeurism.

III.

Whatever the feedback on that scene and other problematic aspects of the film (e.g. its anti-Semitism), it made money. According to IMDB, Rotten Tomatoes, Box Office Mojo, Wikipedia, and other unreliable? sources, during opening weekend the film grossed $83,848,082 while appearing on 3,043 screens. This is significant because the film’s budget was approximately $30,000,000. By March 2005 the film had grossed—in the United States alone—$370,782,930. Apparently this is the/a record for an R-rated film. Worldwide the movie is estimated to have earned $611,899,420. The gore, violence, and suffering didn’t completely turn off moviegoers.

What of the reviews? Did any critics or intellectuals agree with my “Christian torture porn” assessment? Here’s an extended excerpt of Wikipedia’s useful summary of the reception:

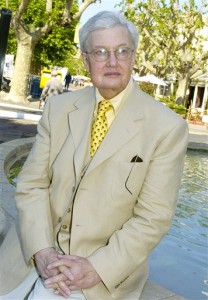

Roger Ebert’s review corresponds most strongly with my memory and impressions of the film. Here’s the opening of his assessment:The Passion Of The Christ polarized critics, with Jim Caviezel’s performance, the musical score, the sound, the makeup and the cinematography being praised, while the film’s graphic violence and antisemitic undertones were singled out for criticism. …The consensus [of Rotten Tomatoes reviewers] states “The graphic details of Jesus’ torture make the movie tough to sit through and obscure whatever message it is trying to convey.” …

Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars, and called it “the most violent film I have ever seen”, also reflecting on how the film personally impacted him as a former altar boy. New York Press film critic Armond White praised Gibson’s work, comparing him to Dreyer, for transforming Art into spirituality. However, Slate reviewer David Edelstein called it “a two-hour-and-six-minute snuff movie,” while Jami Bernard of the New York Daily News called it “the most virulently anti-Semitic movie made since the German propaganda films of World War II.” Time magazine listed it as one of the most violent films of all time. The June 2006 issue of Entertainment Weekly named The Passion of the Christ the most controversial film of all time, followed by Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange.

If ever there was a film with the correct title, that film is Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ.” Although the word passion has become mixed up with romance, its Latin origins refer to suffering and pain; later Christian theology broadened that to include Christ’s love for mankind, which made him willing to suffer and die for us.

The movie is 126 minutes long, and I would guess that at least 100 of those minutes, maybe more, are concerned specifically and graphically with the details of the torture and death of Jesus. This is the most violent film I have ever seen.

On Gibson not providing much in the way of a deeper meaning behind Jesus’ suffering, Ebert wrote:

What Gibson has provided for me, for the first time in my life, is a visceral idea of what the Passion consisted of. That his film is superficial in terms of the surrounding message — that we get only a few passing references to the teachings of Jesus — is, I suppose, not the point. This is not a sermon or a homily, but a visualization of the central event in the Christian religion. Take it or leave it.

Ebert anticipated a poor audience response:

Many audience members…will enter the theater in a devout or spiritual mood and emerge deeply disturbed. You must be prepared for whippings, flayings, beatings, the crunch of bones, the agony of screams, the cruelty of the sadistic centurions, the rivulets of blood that crisscross every inch of Jesus’ body. Some will leave before the end.

And Ebert contextualized The Passion in relation to other biblical epics—even ones discussed in this USIH blog series:

This is not a Passion like any other ever filmed. Perhaps that is the best reason for it. I grew up on those pious Hollywood biblical epics of the 1950s, which looked like holy cards brought to life. I remember my grin when Time magazine noted that Jeffrey Hunter, starring as Christ in “King of Kings” (1961), had shaved his armpits. (Not Hunter’s fault; the film’s Crucifixion scene had to be re-shot because preview audiences objected to Jesus’ hairy chest.)

If it does nothing else, Gibson’s film will break the tradition of turning Jesus and his disciples into neat, clean, well-barbered middle-class businessmen. They were poor men in a poor land. I debated Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ” with commentator Michael Medved before an audience from a Christian college, and was told by an audience member that the characters were filthy and needed haircuts.

I’ll have to let Ebert’s analysis stand because I’m not wild about the Biblical Epic genre. I’ve only seen parts of Quo Vadis, The Ten Commandments, and Ben Hur. And I have no plans to see Exodus: Gods and Kings. Indeed, the whole epic film genre generally turns me off because of the time commitment. If the producers reduced them to bite-sized chunks, I could perhaps absorb them like I do television drama series like The Wire, Sopranos, or Game of Thrones. But, apart from time, I think I just prefer to obtain and review my biblical knowledge through the primary documents and community-tested, vetted interpreters. I don’t trust singular revisionists like Mel Gibson when it comes to theology and Church history.

IV.

Thus far I’ve only casually mentioned the film’s anti-Semitism. Ebert spends six paragraphs of his review on the subject. And the Wikipedia page on the film contains an extensive recounting of the topic. I like Ebert’s brief analysis, so I’ll let me personal reflections suffice. It was clear, to this viewer even while in the theater, that Gibson chose to depict many of Jesus’ persecutors as having stereotypical Jewish features. Jesus, Mary, and the other disciples were portrayed as northern Europeans. Had I not been distracted by the violence, I might have laughed out loud at Gibson’s Eurocentrism. It would’ve been comical were it not so sad in relation to the tradition of Christian anti-Semitism the film embodied. Finally, as Ebert mentions in his review, Jesus’ persecutors are portrayed as a vindictive, uncomplicated, and bloodthirsty bunch. Gibson chose to ignore biblical passages that spoke to more complicated views by historical actors like Caiaphas.

V.

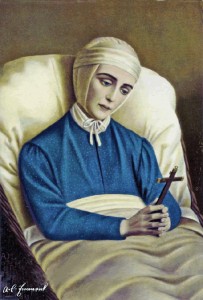

This historical analysis has gone overly long. I thought I would tackle Gibson’s reliance, in the screenplay, on the mystical visions experienced by near-saint/Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich (right). I had hoped to probe the irony of Gibson’s tortuous mysticism, derived from a non-canonical text, in relation to promoting and selling The Passion among Protestants whose beliefs might contain some elements of a sola scriptura ideology (i.e. scripture alone). It also occurred to me that the film promotes the ancient/medieval belief that bodily conformity leads to mental and spiritual conformity–which stands in contrast to what some call a sola fide(i.e. faith alone) theology in Protestantism. Instead I’ll let those teasers stand without further elaboration.

Returning to the present, and to Gibson’s probable hope in producing and directing the film, I’ll offer the following: Just as torture doesn’t reduce terrorism, Christian torture porn doesn’t produce converts. But maybe that didn’t matter to Gibson. Perhaps he was simply a product of his times: a director producing a film in a time of war, while pornography was on the rise and the horror genre had become a legitimate part of the movie landscape. In that context, if it hadn’t been Gibson, perhaps another Catholic director would have (ironically) produced a Christian torture porn epic and marketed it to Evangelical Christians. Perhaps only that kind of violent passion would capture the attention of a distracted, fragmented nation. In those circumstances deeper theological questions about suffering and redemption, whether asked in the context of civil or traditional religion, would have still been second fiddle to entertaining distractions. – TL

—————————————–

[1] Most of that passage is sourced from an article in Evangelical Christians and Popular Culture: Pop Goes the Gospel, Vol. 1 (Robert Woods, ed, ABC-CLIO, 2013). The article is titled “Evangelicals’ Passion for The Passion of Christ,” and authored by John L. Pauley and Amy King (pp. 36-51)

[2] I suppose some of the cuts may have also come form the crucifixion scene.

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Tim this is an interesting analysis. There’s a lot going on here, and a lot to unpack. I’m afraid my comment might be something of a rabbit trail, but the spirit moveth where it willeth, as they say…

Here’s what I’m pondering:

I think it’s worth noting that the definition you’ve used for “pornography” here (the third definition in the MW dictionary) is a kind of figurative broadening of the customary (first) definition of the word. Though none of the definitions imply anything pejorative about the term, the example given in the dictionary actually involves the use of the term as a way of minimizing or dismissing a filmmaker’s work: “If you ask me, his movies are just high-class pornography.”

You used a similar construction above, when writing of the effect — the affect? — of Gibson’s filmic portrayal: “The older story of the tragedy of Jesus’ suffering along the Via Dolorosa doesn’t result in any kind of purgation, but only pornographic voyeurism.” That “only” is interesting to me, and I’m trying to sort out where it comes from, and why it comes so easily as a way of devaluing/dismissing the merits of a work (“only pornography,” “just pornography, etc.).

I think the commonly pejorative use of the term probably has

lessto do with its long history, which you nicely alluded to above, and which is available in the MW etymology given beneath the definitions. It seems to be the connection between pornography and prostitution, commerce in sex, that gives the term its pejorative spin. Behind “just pornography” is another idea — “just prostitutes.”Now, I certainly don’t see that latter idea anywhere in your writing above. Indeed, I’d be surprised to find such a sentiment expressed by anyone on the blog. I guess I’m just intrigued — and maybe a little unsettled — by how “the pornographic” implies the “inauthentic” (or maybe the “incomplete”? the “unfulfilled” or “unfulfilling”?, with modifiers like “only” and “just” accentuating that implication) and how that implication depends upon devaluing sexual intimacy within a commercial setting. This valence of the term becomes especially important, I think, when we’re talking about filmmaking — especially of the “blockbuster” kind — because in that sense it’s all “pornography.” Films offer catharsis in exchange for cash.

I think you’re correct in noting that Gibson’s film wasn’t aiming for any kind of reflective meditation on the meaning of the Passion. It was aiming for a literally visceral response in viewers — to portray these incidents in such a way that people were made to feel something physical. So in the sense that this is a pornographic aim — the point of pornography is, I would argue, to prompt arousal in the reader/viewer — I think your analysis of Gibson’s film may be correct not only in an assessment of its effects but also in an assessment of its aims. I suppose a fan of Gibson’s film might really take issue with such an assessment — but that kind of reaction would have less to do, I think, with a zeal for the conceptual message of the film (whatever it is) than it would with a rejection of the term “pornography” (in whatever sense) because that term seems to carry with it implicit notions of disapproval. (On the other hand, I suppose one might argue that attaching the term “pornography” to what Gibson has done in this film might be giving pornography a bad name. I have more things to say about all this — but that’s at my blog.)

Anyway, I think the way you’ve framed the issue here is interesting and instructive. It’s a reading that is both perceptive and perhaps also dependent upon not perceiving what (all) we mean when we say that something is “pornographic.” Thanks much for the post.

I think of torture porn as more of a genre descriptor of violent, low-brow, and sexually explicit filmmaking than having anything to do pornography as critical label. I first encountered the term attached to the Saw films to describe the fetishization and excess of physical violence in the film. Since then, it has become a kind of meta-genre existing at the nexus of horror, thriller, and action. According to Wikipedia it’s closely related to the splatter or gore film genre and its pioneer was George Romero.

I think it’s interesting to put the “Passion of the Christ” alongside other torture porn films since it was clearly intended for a different audience and meant to convey an opposing set of values (bodily suffering as redemptive v. as an end in itself). I think what Mel Gibson was attempting to do with “Passion” is to use violence and gore to connote seriousness. Other critically films of that era like “Gangs of New York” trafficked in shocking violence to combat the gloss of major motion picture filmmaking. “Passion” is more extreme than these other films and failed to find their critical acclaim. Still, I think Gibson was trying to duplicate their success.

Wait, does “torture porn” have a distinct Wikipedia entry? If so, how did I miss that? – TL

And I think you’re right, Matt, about Gibson using torture/gore as a supplement to seriousness. I didn’t explicitly think about *Gangs of New York* when I wrote this post, but I think it was in the back of my mind for its so-called “operatic violence.” – TL

Lora: Thanks for your long and, as always, thoughtful comment.

I confess to trading on the *connotations* of pornography/pornographic in terms of any thinking Christians that might read this post. I wanted them to FEEL the disjunction between their beliefs about Jesus and how Gibson portrayed Jesus in the film. Otherwise, I was *absolutely* not denigrating sex work. In my mind there is no such class of persons as a “just prostitutes.” I used the MW definition to draw attention, as you noted, to another stylistic use of the word/term. But anyway, thanks for giving me an opportunity to clarify on a potential reader perception.

You’re absolutely right about the “a lot going on here.” Too much. As I rethought my post this morning (much like pro sports players replay the game from the night before), I tackled too much. Or perhaps Gibson gave us so much to say. I perhaps should be giving him credit for knowing some of the irony and disjunction I’ve posited above. I also wanted to go deeper into audience reception, and underscore something about the rise of so-called “Evangelical Catholics.” And then I could’ve dived deeper into Gibson’s filmography (as a perceptive commenter noted on the Facebook page) and maybe even talked more about the psychology/theology of suffering. – TL

Because I was pressed for time, I excluded a section of Ebert’s review that I had wanted to dissect (and it goes with my regret above about wanting to dive deeper into theology). Here’s that section—and please attend to Ebert’s final paragraph:

————————————————–

“The Passion of the Christ,” more than any other film I can recall, depends upon theological considerations. Gibson has not made a movie that anyone would call “commercial,” and if it grosses millions, that will not be because anyone was entertained. It is a personal message movie of the most radical kind, attempting to re-create events of personal urgency to Gibson. The filmmaker has put his artistry and fortune at the service of his conviction and belief, and that doesn’t happen often.

Is the film “good” or “great?” I imagine each person’s reaction (visceral, theological, artistic) will differ. I was moved by the depth of feeling, by the skill of the actors and technicians, by their desire to see this project through no matter what. To discuss individual performances, such as James Caviezel’s heroic depiction of the ordeal, is almost beside the point. This isn’t a movie about performances, although it has powerful ones, or about technique, although it is awesome, or about cinematography (although Caleb Deschanel paints with an artist’s eye), or music (although John Debney supports the content without distracting from it).

It is a film about an idea. An idea that it is necessary to fully comprehend the Passion if Christianity is to make any sense. Gibson has communicated his idea with a singleminded urgency. Many will disagree. Some will agree, but be horrified by the graphic treatment. I myself am no longer religious in the sense that a long-ago altar boy thought he should be, but I can respond to the power of belief whether I agree or not, and when I find it in a film, I must respect it.

————————————————–

I’ll delay commenting until I hear from others. But this goes to my point in the post about finding, after the fact, that my perspective corresponded largely with Ebert’s (I purposely waited to read his review until I got to that section of my post). – TL

Thanks for that sketch of the genre, Matt.

In talking about 21st century filmic gore, we are in some ways far removed from Karen Halttunen’s work on “the pornography of pain” — but in other ways, not so much.

Here’s a link to the article in JSTOR: Humanitarianism and the Pornography of Pain in Anglo-American Culture.

Torture porn does not have a distinct Wikipedia entry, but is listed as a sub-genre of the splatter or gore film.

Got it. …I was sure I had missed some important topics/thinking if there was a distinct entry.

I, too, went to see the film in, I think, its opening week–I was writing for a campus newspaper and it fell to me to review it–and the atmosphere of the theater before, during, and after was the strangest I have ever encountered. Sitting in the audience felt to me, in fact, to be akin to what I can only imagine sitting in a pornographic theater felt like–no one wanted to acknowledge anyone else’s presence, no one wanted to draw attention to themselves. There was no conversation detectable before the projector turned on, and none after the credits rolled.

Of course, that might have just been the atmosphere of the cinema I was in. I know many churches bussed in whole groups of people who, I suppose, had to acknowledge one another’s presence, and I recall hearing anecdotes of audience members in various parts of the country weeping loudly or having fits or something very demonstrative and involuntary. So maybe there were different atmospheres in different places. But the deep desire for anonymity or even invisibility that permeated the theater I was in was really something strange.

Mel Gibson should be brutally flogged and nailed onto a cross for making this movie.