The following guest post is by David Sessions, a doctoral student in history at Boston College, and the founding editor of patrolmag.com. David was formerly the religion editor of The Daily Beast, and has also written for Slate, Newsweek, Jacobin, and others.

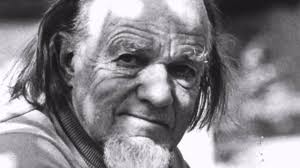

Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984) is widely credited with motivating conservative evangelicals in the U.S to engage with secular thought and art. Where previously these philosophers and cultural figures had been regarded as dangerous and beyond hope, Schaeffer arrived on evangelical college campuses in the 1960s with electrifying lectures on the history of Western thought, drawing his famous “line of despair” across the blackboard and pinpointing Hegel as the moment when philosophy gave up hope of reconciling reason and meaning.

Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984) is widely credited with motivating conservative evangelicals in the U.S to engage with secular thought and art. Where previously these philosophers and cultural figures had been regarded as dangerous and beyond hope, Schaeffer arrived on evangelical college campuses in the 1960s with electrifying lectures on the history of Western thought, drawing his famous “line of despair” across the blackboard and pinpointing Hegel as the moment when philosophy gave up hope of reconciling reason and meaning.

Evangelical scholars after Schaeffer, as well as the few historians who have begun to investigate his impact, have not been kind to his interpretations of Western thought, which often featured unusual chronologies, glaring omissions, and idiosyncratic readings. [1] Nevertheless, Schaeffer remains fascinating for his extraordinary influence on evangelical thinkers and leaders, and his genuinely sympathetic efforts to engage the great thinkers of European history that he saw as struggling against a tide of civilizational despair.

This post will focus on the peculiar position of Hegel in the earlier versions of Schaeffer’s intellectual genealogy. As a European intellectual historian, I’m especially interested in how Continental philosophical ideas made their way into the “intellectual histories” that echoed throughout conservative evangelical thought, and how those both compare with and differ from more contemporary conservative responses. My preliminary hypothesis is that Hegel came to occupy this pivotal negative role in Schaeffer’s earlier thought because of the similarities, rather than the differences, between Schaeffer and Hegel’s identification of logic and metaphysics. It seems that the largely self-taught Schaeffer understood Hegel as poorly as he understood many other thinkers, including Aquinas. [2] But it’s also possible that his conclusion that Hegel was deadly to Christian faith mirrored the conclusions of earlier Protestant-fundamentalist orthodoxies, including the early 19th-century German one in which Hegelian theology came under ferocious attack from reactionary theologians.

Logical Metaphysics, or, Antithesis vs. Synthesis

It is impossible to follow Schaeffer’s readings of philosophy without some acquaintance with his overall system. (I call it a “system” or a “metaphysics” for convenience even though that risks overstating its coherence.) A crucial moment in Schaeffer’s genealogy of what he called modern pessimism or despair is a supposed divorce between “rationalism” and “rationality.” “Rationalism” is Schaeffer’s epithet for humanist philosophy that rejects the possibility of a reason-based explanation for meaning and values; “rationality,” on the other hand, denotes Schaeffer’s brand of rationalism: a view that not only is physical reality based on rational laws, but that these laws encompass human meaning, values, and morality. This entire system of logical necessity follows from the “antithesis” at the root of metaphysics—the distinction between something and nothing. God is the “something” of metaphysics, and the fact that humans exist, experience their lives meaningfully, and see rational order in nature proves that God created the world to operate according to the central truth of antithesis, an absolute distinction between being and nothingness, truth and falsity. As Schaeffer wrote in Escape from Reason (1968):

Antithetical thought was not begun by Aristotle—it ultimately rests on the reality that God exists in contrast to His not existing, and on the reality of His creating what exists in contrast to what does not exist—and then to His creating people to live, observe, and think in the reality. [3]

Though many of the details of this argument remain highly ambiguous, what Schaeffer aimed at was a kind of Kantianism without the distinction between the realms of noumena and phenomena; the tradition doctrine of the personal, creator God as absolute rational necessity, not just in human perception, but in reality itself. The great error of materialist rationalisms, according to Schaeffer, is that they are contradicted by the human experience of world that is both meaningful and rational. Neither the nihilist who believes in total chaos nor the naturalist who believes in a meaningless rational order can live consistently with his principles. Thus, these “worldviews” are self-refuting, and lead people to try to sneak meaning into their lives via irrational means (Kierkegaard’s leap of faith, or 60s drug culture). For Schaeffer, the ultimate test of a philosophy is whether its adherents can live it out consistently; because no one can really live as if the world is irrational and/or meaningless, the traditional Christian view of a meaningful, ordered world created by God is “not the best answer to existence; it is the only answer.” [4]

In many respects it remains mysterious how “antithesis” can serve as the basis of metaphysics as well as the definition of logic and truth. But it is not difficult to see why Schaeffer would see Hegel as the ultimate challenge to this picture; the latter is above all known for his dialectical logic, often encapsulated as the triad “thesis-antithesis-synthesis.” As Schaeffer biographer Barry Hankins notes, Schaeffer identified Hegel’s thought with relativism. [5] Because the very structure of reality is rooted in a division between God and nothingness, a denial of this basic logic is a denial of the possibility of truth or any rational access to God. “[Hegel] opened the door to that which is characteristic of modern man: truth as truth is gone, and synthesis (the both-and), with its relativism, reigns.” [6] In Hegel and especially in Kierkegaard (Schaeffer frequently collapsed them into the same moment), philosophy crosses the “line of despair”: it has given up hope that meaning and faith can be fit into the structure of reason. As Schaeffer put it in The God Who is There (1968): “With Hegel and Kierkegaard, people gave up the concept of a rational, unified field of knowledge and accepted instead the idea of a leap of faith in those areas which make people distinctive as peoples—purpose, love, morals, and so on. It was this leap of faith that originally produced the line of despair.” [7]

Anyone familiar with Hegel will probably know that this is something like the opposite of what he believed himself to be doing. In fact, Hegel’s aim was very similar to that of Schaeffer’s: he came of age in the context of the Romantic reaction to Kant’s separation of the autonomous subject from the real world, from access to things in themselves. Similarly to Schaeffer, Hegel rejected Romantic subjectivism by attempting to reconcile reason and reality. Reason became no longer just the structure of the human mind, but the structure of reality itself; the dialectical operation of consciousness is what allowed the human consciousness to be reconciled with reality through a process of negation into synthesis. Truth is the result of this process, the culmination of reason in the absolute whole, or God. [8] Hegel hardly gives up on a “rational, unified field of knowledge”; his system is intended to explain precisely how such a thing would be possible. As is well known, Hegel considered his thinking to be the full philosophical expression of the truth of Christianity, what traditional Protestant faith represented in narrative and practical terms.

It has been noted by Hankins, among others, that Schaeffer’s original genealogy of Western thought omitted Romanticism, a curious move for a thinker whose primary target was subjective relativism. [9] Ironically, Hegel rejected his early identification with the German romantics, believing that the romantic effort to re-unite the individual with the world needed to take a systematic and rational—rather than an expressive and artistic—form. [10] There are many other Hegelian motivations Schaeffer might have found congenial: the strong emphasis on rational thought as ultimate means of access to reality, and the identification of reason with being. Though Hegel was not limited by an orthodox or biblical conception of Christianity, he understood his philosophy as the ultimate means of encompassing the whole of human experience into the rationality of God. Schaeffer was aware of Hegel’s religious impetus; he admitted, “[Hegel] hoped for a synthesis which somehow would have some relationship to reasonableness, and he used religious language in his struggle for this.” [11] But Hegel’s synthesis was irreconcilably opposed to Schaeffer’s own rational metaphysics, in which reason and truth were defined as “antithesis.” Hegel “changed the rules of the game,” and ushered in not just philosophical but political chaos:

Instead of antithesis (that some things are true and their opposite untrue), truth and moral rightness will be found in the flow of history, a synthesis of them. This concept has not only won on the other side of the Iron Curtain; it has won on this side as well. Today not only in philosophy but in politics, government, and individual morality, our generation sees solutions in terms of synthesis and not absolutes. When this happens, truth, as people had always thought of truth, has died. [12]

Hegel and the Negation of the Personal God

Schaeffer’s presentation of Hegel as the enemy of reason and truth was hardly the first time the German philosopher had been attacked as a threat to political order. In his own day, Hegel was attacked both by fundamentalist Pietists and by more moderate theologians like Immanuel Hermann Fitche as a “pantheist” who denied the personality of God, which in early 19th-century Prussia was closely linked to the legitimacy of the king. While Hegel always considered himself a Christian philosopher and many of his followers were theologians, Warren Breckman writes, “very few non-Hegelian Christians entertained seriously the notion that Hegel was anything but poisonous to religious belief.” [13] The criticism, from various strains of orthodox and “speculative” theology, centered on the fact that Hegel’s philosophy supposedly denied the personality of God by diffusing divinity into “spirit” (Geist). As Prussia’s political atmosphere grew more intensely reactionary following the July Revolution in France, the individual personality of God was reasserted as the necessary basis of its embodiment in the absolute monarch. When Frederick William IV took the throne in 1840, he appointed reactionary philosophers with the express order to “slay the dragon-seed of Hegelian pantheism.” [14]

A number of Hegel’s followers had also come to recognize the ambiguity of Hegel’s philosophy of religion; several of them, including David Friedrich Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach, concluded that Hegel’s explicit reconciliation of his philosophy with traditional Christian faith had been incoherent at best, and at worst a capitulation to the forces of order. By the early 1840s, they had rejected Hegelian theology for various strains of materialist humanism.

While Schaeffer’s interest in creating an impregnable logical defense of Christianity was much more thoroughly modern in its orientation, it shared the German fundamentalists’ concern that Hegelianism’s diffusion of God into a universal process of reason was fatal to literal belief in orthodox Christianity. In both accounts, the personality of God, as described in Scripture, was necessary for faith to make any sense and for political order to be maintained. For Schaeffer, a particular kind of anti-Hegelian logic, where the possibility of absolute synthesis was denied, was necessary to accomplish the Hegelian goal of integrating man’s experience with into the knowledge of God. Ironically enough, Feuerbach, who would ultimately describe Christianity as an alienation of man from his true being, also interpreted Hegel as having demolished the foundations of traditional religion. As John Toews puts it, Feuerbach “interpreted the philosophy of absolute spirit as a radical negation of the presuppositions of Christian culture (subjective egoism, the dualism of spirit and nature, the separation of the transcendent and the immanent), and defined his historical task as the actualization of the Hegelian absolute in a post-Christian cultural order.” [15]

Whether or not Schaeffer ever truly understood Hegel, he recognized something that politically conservative religious fundamentalists before him had: despite the assurances of the master himself, Hegel’s philosophy had an extremely ambiguous relationship to traditional religion. And it perhaps had far more revolutionary political implications than Hegel was willing to admit.

* * * *

Notes:

1. See especially Barry Hankins, Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America (Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Pub., 2008).

2. Molly Worthen, Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, 2014, 212.

3. Francis A. Schaeffer, The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: The Three Essential Books in One Volume. (Westchester, Ill.: Crossway Books, 1990), 229.

4. Ibid., 288.

5. Barry Hankins, Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2008), 87.

6. Schaeffer, The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy

, 233.

7. Ibid., 43.

8. G. W. F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. Arnold V. Miller (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), 11–12.

9. Hankins, Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America, 173.

10. John Edward Toews, Hegelianism: The Path Toward Dialectical Humanism, 1805-1841 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 51.

11. Francis A. Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live?: The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture (Old Tappan, N.J.: F.H. Revell Co., 1976), 162-3.

12. Schaeffer, The Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy, 233.

13. Warren Breckman, Marx, the Young Hegelians, and the Origins of Radical Social Theory: Dethroning the Self (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 42.

14. Ibid., 63.

15. Toews, Hegelianism, 328.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

A topic I find quite fascinating, David. Thanks for posting this.

When I first read Schaeffer as an evangelical student my freshman year at a public college, I remember thinking, “His reading of Hegel doesn’t sound quite right. For such a supposedly great thinker, Schaeffer’s summary of his ideas seems a little too simple.”

In your reading, have you come across anything that indicates what actual reading Schaeffer did that might have influenced his view of Hegel? To be quite honest, I wonder if he ever actually read The Phenomenology of Spirit. I know he got many of his ideas from magazine articles and conversations.

I’m sure he did actually read some of the books he mentioned, but his engagement is usually so cursory that it’s hard to tell. He acknowledges a couple of times that Hegel is “much more complicated.” At one point he summarizes Foucault’s “Madness and Civilization” and explicitly says he got it from a review in the NY Review of Books. So I think that was typical, but it’s hard to know for sure.

Barry Hankins — who is certainly more sympathetic to Schaeffer than Molly Worthen — says there’s reason to believe Schaeffer did not read the thinkers he criticized:

“While there can be no certainty on this point, it is highly unlikely that Schaeffer ever actually read Hegel, Kant, Kirkegaard, and the other modern thinkers he would later critique in his lectures and books. It is doubtful that he even read Barth in depth. Schaeffer’s knowledgee of these thinkers was superficial, and as mentioned above, he made mistakes with regard to details. Schaeffer was a voracious reader of magazines and the Bible, but some who lived at L’Abri and knew him well say they never saw him read a book. It appears highly likely, therefore, that Schaeffer learned western intellectual history from students who had dropped out of European universities”

Great to see more attention given to Schaeffer and his *fit* in to Western intellectual history. I’ve written elsewhere about Schaeffer’s problems as those of the “generalist” confronting the “specialist”–a problem that Schaeffer’s contemporary Reinhold Niebuhr has also faced:

http://usreligion.blogspot.com/2014/01/writing-about-francis-schaeffer-and.html

I’m wondering, too, how much we might talk about a “Wheaton school” of intellectual history interpretation and apologetic use. Schaeffer didn’t attend Wheaton, but he did draw heavily from Wheaton grads like Carl Henry and Edward John Carnell, who in turn drew from their mentors Gordon Clark (Wheaton) and Cornelius Van Till (Westminster, where Schaeffer did study for a spell).

Thanks, David, for this rich and compelling reading of Schaeffer in the larger history of Hegel reception. I learned tons and enjoyed your provocative conclusion that Hegel as read through Schaeffer might indeed be more revolutionary than most intellectual historians have long contended.

Although I think you’re correct that Schaeffer’s reading of Hegel is curious, such a reading does make logical sense if we limit ourselves to Schaeffer’s peculiar and eclectic system of apologetics, don’t you think? As you make clear, Schaeffer contended that Western Civilization had become post-Christian in its rejection of antithesis, a method of thought based on the proposition that, since *this* is absolutely true, *that* is absolutely untrue. Thus it makes sense that Schaeffer argued that Hegel represented the first step towards the post-Christian line of despair because Hegel theorized that synthesis, not antithesis, was the superior method of thought. Synthesis, in Schaeffer’s reading of Hegel, implied relativism, since all acts, all gestures, had an equal claim to truth, in that the dialectical process would eventually envelop everything. Napoleon’s conquest of Europe was not to be judged by the brutality of its individual acts, but by the synthesis of the “world spirit on horseback” that Hegel famously believed Napoleon signified.

Absolutely! I don’t disagree with anything in your second paragraph; as far as I can tell, that was my argument. When I said it was ambiguous or incoherent, I didn’t mean the reading of Hegel in particular – you can see exactly why Schaeffer read him the way he did. What’s remains ambiguous is how “anthesis” serves as the basis of all the things Schaeffer wants to gather into his web of things that logically follow from it; a lot of that is simply asserted or assumed.

Ok, yes, that’s a fine point.

Love seeing real critical engagement of religious ideas as part of intellectual history. Lots to think about here. Thank you David.