Last week I discussed the year 2015 and the potential it holds for memory of both the end of the Civil War (1865) and several key turning points in both American domestic and foreign policy histories (1965). Today I’ll shift focus to the year 1865, and in particular emphasize why it’s important the period be marked with a national focus on the potential of Union victory, Emancipation, and Confederate defeat—and how the aftermath of this era created the modern nation we know today. Before I continue, I’d like to address an important point made by one of our frequent commenters, Kahlil Chaar-Perez, in the comments for my post last week.

His point that we make sure to differentiate between official, government-sponsored commemorations and more partisan affirmations of the past was an excellent  one. And, as 2014 ends and 2015 begins, it’s important to take stock of just what that means. For instance, the events in Ferguson this year have caused some historians to point out the historical continuity between those incidents and the events of the early long, hot summer of 1964. That’s certainly not the stuff big, national celebrations are made of. But it’s always important to consider how both partisan and nonpartisan organs of news and opinion remember the events of the past—without having to worry about crafting a government-sponsored narrative. And even government sponsored narratives are malleable because, after all, governments change.

one. And, as 2014 ends and 2015 begins, it’s important to take stock of just what that means. For instance, the events in Ferguson this year have caused some historians to point out the historical continuity between those incidents and the events of the early long, hot summer of 1964. That’s certainly not the stuff big, national celebrations are made of. But it’s always important to consider how both partisan and nonpartisan organs of news and opinion remember the events of the past—without having to worry about crafting a government-sponsored narrative. And even government sponsored narratives are malleable because, after all, governments change.

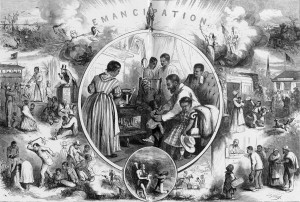

With that said, remembering 1865 and the end of the American Civil War is all the more important because it was a pivotal year in American history. Any celebration of the events of 1865 (Appomattox Court House, the passage of the 13th Amendment, Lincoln’s death, etc.) should be used to do two things: mark the end of the war and the beginning of the Reconstruction era. That second part would be a bit trickier, because you’d be attempting to explain a complex time period to Americans. And it’s a time period that, I’d argue, hasn’t been remembered very well in popular culture. Just think of a common trope in Westerns: the ex-Confederate soldier who has gone to the Western United States for a new life. The most recent example of this is Hell on Wheels

, but many of you know about other examples (the Clint Eastwood-Sergio Leone “Spaghetti Westerns” spring to mind). I include these in Reconstruction popular narratives because, well, the cowboys are trying to escape something—in this case not just the East as an idea, but the upheaval and chaos of Reconstruction in particular.

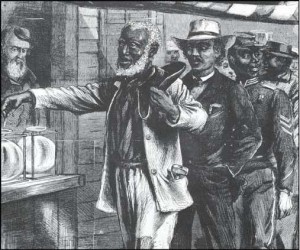

I don’t have to say much about Birth of a Nation or Gone With the Wind in regards to their take on Reconstruction—both films are well known for being the pillars of the Southern “Lost Cause” on the silver screen. However, the miniseries Roots could be considered part of an alternate Reconstruction narrative. Don’t forget that a significant part of the miniseries deals with the Civil War and its aftermath, and it captures something I like to refer to as “the Spirit of ‘65”—1865, that is. What I mean here is a two-headed spirit: one head for the hopefulness felt by the millions of recently freed black men and women in the south (along with quite a few Union soldiers who supported both a war for Union and Emancipation); the other head signaling an uneasiness with the sudden revolution in the South that came to a head in 1865.

The 1990 film Glory, about the 54th Massachusetts, is also an example of this Spirit of ’65, albeit two years before the war’s end. Here, the hopes and fears of African American men going off to fight for freedom is masterfully captured. It’s a shame we haven’t seen any films centering on the African American soldier’s experience during the Civil War—although Lincoln (2012) certainly does include some of their voices. Hollywood could do worse than producing more films and television shows centered around, say, an African American veteran of the Civil War trying to raise a family in 1860s and 1870s Mississippi or South Carolina, and becoming politically active while at the same time  resisting White Leagues or the Ku Klux Klan.

resisting White Leagues or the Ku Klux Klan.

Of course, that’s a pop culture example—other manifestations of public memory, such as museums, are crucially important as well. Now, this isn’t meant as simply a personal plug, but friends of mine here at the University of South Carolina have had to deal with this issue first hand. The recent renovation to the Woodrow Wilson Family House, for instance, has given the men and women in charge that site the opportunity to use the home as a place to teach visitors about Columbia during the Reconstruction era. It hasn’t been easy—far too many people still cling to the “Lost Cause” narrative of the South being a vulnerable, oppressed region during the period. But with scholars such as Jennifer Taylor, for example (a good friend of mine—but trust me, her work is very important and deserves your attention if you care about Reconstruction memory) working in the state on how we think about Reconstruction, it’s clear that memory of the end of the Civil War—and the start of the modern American Republic—is being molded and contested as we speak.

I’ve only scratched the surface of this question. Next week I’ll return to it, with the help of a few dear friends of mine.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Like always, excellent stuff, Robert! And I am humbled by the fact that you used my comment as a springboard for this intervention. What your colleagues at USC are doing is necessary work. Which brings me to the question that I still have: can we call what they are doing an act of commemoration? Maybe I am overcomplicating things, but I see a difference between what you call “celebration of the events of 1865,” which tends to have a monumental and univocal–if not fossilizing–lens regarding the historical event, and more open-ended, critical acts of remembrance, such as “teaching visitors about Columbia during the Reconstruction era.” Both forms of memory can be enacted by the state and its citizens.

By the way, my name is Kahlil and not Khalil, and there’s an accent in Pérez. No biggie, of course, but I put this out so everybody can read it, since it’s not the first time it’s happened. Funny thing: instead of following the Arabic form, my parents reproduced the proto-new agey Lebanese writer’s Kahlil Gibran’s decision of writing his first name in English. Another symptom of US colonialism in Puerto Rico? You be the judge. 🙂 ).

Apologies for misspelling your name–still don’t know how I did that.

And you’re right, certainly–the state can do both a critical analysis of the past, and I’d say that is what my colleagues are doing. What I’m getting at here is, well, what *kind* of critical analysis, if any, will we get next year for events marking the end of the Civil War and the start of Reconstruction.

I too look forward to what 2015 might bring in this regard (as well as the silences, which always carry their own meanings). It would be great if Coates continued the incisive work he has being doing the past couple of years on the Civil War, but around the idea of Reconstruction. Any chance he has mentioned this?

Kahlil Chaar-Pérez, you ask a question I have been contemplating recently, especially after reading Karen Cox’s study on the United Daughters of the Confederacy. I personally feel that my work at the Woodrow Wilson Family Home is commemoration. I often wonder if I am presenting a more accurate narrative with the same zeal as the UDC. One can only hope for same effectiveness but with a more positive impact.

Thanks for the reply, Jen!

First of all, kudos for the fabulous work at the Woodrow Wilson Family Home, I was parsing through the website and the project looks amazing. Indeed, to read the Reconstruction era through the Wilson home could be understood as an open-ended form of memory that in its critical (and affective) power clearly goes beyond the conventional acts of commemoration that I was trying to describe.

A minor point, but 1865 marked the first (and in some places mostly successful) attempt at the seizure of power in The South by former Confederates; Reconstruction really began in meaningful terms in 1867. 1865 and 1866, meanwhile, saw the creation of new state constitutions created by White-only constitutional conventions and the creation of highly restrictive Black Codes in South Carolina and other Southern states. 1866 saw violent resistance to Federal authority in New Orleans and Memphis, among other Southern cities. White Southern voters sent former Confederate soldiers to Washington in the first elections held under the terms of Presidential reconstruction, and everywhere across The South measures were taken to perpetuate the ante-bellum social and political order. This counter-revolution was so pervasively successful that it lead Frederick Douglass to express despair at what the 18 months since Confederate capitulation had brought, when, writing in The Atlantic Monthly in 1866, he described the United States and its formerly rebellious region as “…the merest mockery of a Union, — an effort to bring under Federal authority States into which no loyal man from the North may safely enter, and to bring men into the national councils who deliberate with daggers and vote with revolvers, and who do not even conceal their deadly hate of the country that conquered them….”

In marking the sesquicentennial of the official beginning of Reconstruction, this faltering start should not be omitted.

1865 did in fact mark the end of formally declared warfare between the Confederacy and the Union, but genuine Reconstruction would have to wait two more years to begin.

You’re exactly right–this is something that has to be marked as well. In many ways I alluded to this with my two-headed analogy–the fear of the future being shown by how white Southerners quickly closed ranks to shut down any attempt by African Americans to assert any sort of idea of freedom.