This week’s reading comprised Chapters Six and Seven, which in fact (this was not premeditated on my part) have a certain unity, swirling around Harald Petersen, the husband of Kay and, as we’ve found out, the lover of Norine, a Vassar graduate who was not a member of “the group,” but a sort of bitter admirer of their wealth, beauty, and self-assurance.

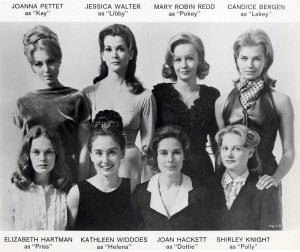

What is surprising, however, is that this focus on Harald allows McCarthy to move into the consciousnesses—in what is generally referred to as a close-third person point of view or free indirect discourse—of persons beyond the women of “the group.” Rather than a section from Pokey Prothero’s point of view, we have one from her family’s butler, Hatton; rather than another section from Dottie Renfrew’s point of view, we have one from her mother’s. Helena Davison has the whole of Chapter Six narrated from her viewpoint, however.

Why McCarthy would decide to leave the actual members of “the group” for their families and servants is more than a little obscure; perhaps the fuller meaning of these characters will be revealed by subsequent events, but I do have a guess.

Helena’s chapter ends with a conversation with her mother, in which they discover a news article relating the story of Harald’s arrest in connection with a protest staged in an upscale hotel dining room on behalf of a waiters’ strike in New York. Harald, Kay, Norine, and Norine’s husband Putnam—a fundraiser for labor groups—along with some New York celebrities had gone in evening dress to dine at this hotel, knowing that the waiters were non-union. Upon “discovering” this fact, Harald and Putnam make speeches and ask the diners to join them in a walk-out. The hotel manager calls the police.

The news of this incident circulates through Chapter Seven as well—it is what Hatton and Dottie’s mother read and react upon—but it takes a special meaning in relation to Helena, who has only the week before listened to Norine’s confession that she is having an affair with Harald under the noses of both Kay and Putnam. Remarking on a blurry picture in which Harald, Putnam, and Norine are all visible and wearing evening dress, Helena’s mother asserts that she knew a woman must have been involved: “I knew it! ‘Cherchez la femme,’ I said… ‘You mark my words; you’ll find there’s a woman behind this.’” Helena, unsure if her mother has somehow divined the fact that Norine is connected with both of the arrested men, asks her to elaborate and is told that the theatricality of the demonstration—the evening dress, the false spontaneity of the “discovery” of the non-union waiters—reminded the mother of suffragette actions. (N.B., a fantastic monograph on theater and the early women’s movement which you should definitely read is Susan Glenn’s Female Spectacle: The Theatrical Roots of Modern Feminism.) But Mrs. Davison also has more to say.

“No grown-up man,” said her mother, “will ever put on a tuxedo unless a woman makes him. No man, whatever his politics, Helena is going to put on a tuxedo to go out and sympathy-strike, or whatever they call it, unless some artful woman is egging him on. To get her picture in the paper… That tiara now—probably she wanted to wear that. And those gloves. It’s a marvel to me she didn’t have an ostrich-feather fan” (187-188).

“Cherchez la femme” became a sort of noir cliché in the years between the action of the novel—1933—and McCarthy’s writing of it—1963—although it is much older than that, deriving from a line in Dumas’s 1854 novel Les Mohicans des Paris, which deftly crossed the titles of Cooper’s famous epic and Eugène Sue’s massively popular Les mystères de Paris. “You’ll mark my words; you’ll find there’s a woman behind this,” or some such formulation, was the go-to theory for most private eyes in pulp fiction and film when they were confronted with an odd case.

But it is precisely this notion that men act strangely because a woman is surreptitiously bidding him to act in such a manner to impress her that is in some crisis in these chapters. All the women of the group are trying to figure out how to act on their own behalf, how to divert some of the vast resources of energy which have gone into head games with husbands, fathers, fiancés, and boyfriends into direct pursuits of their own goals. One of the principal ploys or stratagems often used by their mothers (and much further back than that), sacrifice, is explicitly disavowed by Dottie. Her mother protests to her,

“Women in my day, women of all sorts, were willing to make sacrifices for love, or for some ideal, like the vote or Lucy Stonerism [i.e., retaining one’s maiden name]. they got themselves put out of hotels for registering as ‘Miss’ and ‘Mr.’ when they were legally married. Look at your teachers, look at what they gave up. Or at women doctors and social workers.” “That was your day, Mother,” Dottie said patiently. “Sacrifices aren’t necessary any more. Nobody has to choose between getting married and being a teacher. If they ever did. It was the homeliest members of your class who became teachers—admit it. And everybody knows, Mother, that you can’t reform a man; he’ll just drag you down too. I’ve thought about this a lot, out West. Sacrifice is a dated idea. A superstition, really, Mother, like burning widows in India. What society is aiming at now is the full development of the individual.” (227-228)

That is a ripe paragraph if there ever was one, and as we discussed last week, quite tricky in its rather overt “timeliness” (or “datedness”) on both the level of the early 1930s and the level of the early 1960s. The sour grace of hindsight looks at Dottie’s self-assurance through the prism of post-Second Wave works like Wendy Wasserstein’s The Heidi Chronicles

or Diane Keaton’s Baby Boom (a sadly neglected film) and worries about Dottie’s belief that “sacrifices aren’t necessary any more.”

Dottie’s philosophy is, to add yet another layer—the present—“Lean In” avant la lettre.

There is a great deal more to talk about—I’m still a little befuddled by the sudden appearance of Hatton, a sort of Jeeves-like figure who seems completely extraneous to the plot yet introduces, I suppose, a sort of half-formed discussion of class privilege. And I didn’t even touch Norine and Helena’s blisteringly frank discussion, which has its own raw issues of class as well as (I think) some intentionally clumsy attempts at aesthetic theory.

At any rate, what stood out to you? Where are these women going?

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andy, I think your observation re: the doubled time of the book is spot on. IOW, McCarthy’s characters are in the 30s, and she has “set” the story in that time, but she is writing of/to her moment in the 60s. Dottie’s insistence on selecting domesticity over daring, and her mother’s frustration, reads like a fictional counterpart to Betty Friedan’s explanation of how the daughters of the First Wave feminists retreated into the domestic and were less ambitious, less accomplished, less interested in challenging and being challenged, than their mothers’ generation. (In many ways one could argue that *The Group* as a whole is sort of the fictional counterpart to *The Feminine Mystique.*)

There’s a great deal of irony in Helen’s mother and her “prophetic soul” — who is more stagey, more performative, more dramatically scripted, more intent on insisting that her daughter play a role, than Helen’s mother?

Helen’s interview with Norine in chapter 6 is incredibly written. The explicit invocation of aesthetic theory may be a tad bit contrived, but Helen’s inner voice — her judicious critical eye — is bracing. Reading this, I recognized why people must have been *terrified* of the prospect that Mary McCarthy might put her thoughts about them into words. There is no mercy in that gaze, and no fear in speaking what she sees.

Chapter 6 could just as well have been called “Venus in Furs” — so many pelts and hides and furs and feral she-critters in heat. And chapters 6 and 7 are both educative in that regard — a lot of advice being given about sex, and a lot of discussion of “the varieties of sexual experience” and how to get along in a world of intimacy that is rather different from whatever one has picked up from romance novels or education manuals. (Chapter 6 features another interesting juxtaposition of reading about sex v. having it.)

On the score of advice giving — of all the mothers we’ve encountered so far in the book, Dottie’s mother is the only one who invites our sympathy or respect, I think. The last paragraph of chapter 7 is very touching. “An idea of a lost lover, of someone renounced, tapped at her memory like a woodpecker.” She is mourning the loss of herself — her self — in marriage. It’s quite the bucket of cold water, when even “happily ever after” — and I think we’re given to understand that hers was and is a happy marriage — means (to borrow an image from Dottie) self-immolation.

L.D.,

Now that I’m returning to this great comment (so belatedly), one thing about the way that McCarthy handles her doubling of historicities–the 30s and the 60s–is how careful she is to prevent the relationship between those decades from falling into a simplistic relationship of either reiteration or counterpoint. Women reading in the 1960s may very well have been instructed by the book on certain matters of sex, but the novel doesn’t seem to me to be set on giving true moral instruction–either using the errors of an earlier time to forearm the present or holding it out as a superior solution to present-day quandaries. The point for me of these cross-generational conversations–and even the intra-generational convo between Norine and Helena–is that they don’t help. No wisdom is truly passed because no one, regardless of their generation, truly has it. Each woman ultimately has to make her largest decisions alone: whether to go through with a marriage, to remain married, to divulge a secret, or–in the next section we read–to impose a feeding plan on a resistant infant. There’s a sort of low-key existentialism to the book that I see emerging.

Another very important feature of these two chapters: the function of the newspaper. Sure, it’s a plot device, but *how* it’s a plot device — indeed, *that* it’s a plot device — is of historical interest. (I posted about newspapers as markers of modernity here.)

BTW, the NYT is offering 50% off for 26 weeks on subscriptions — home delivery and/or all digital. Sale ends on Sep. 3, I think. I signed up last week — got my first Sunday paper this morning! Alas, no butler to bring it to me on a tray — had to go fetch it from the driveway myself. I’ll live.