It is difficult to consider where one would start when describing the previous week. Events in places as diverse as Ferguson, Missouri and Mount Sinjar, Iraq have gripped the attention of people all around the world, and it appears that the crises in both regions have no discernible end in sight. Meanwhile, the deaths of Robin Williams and Lauren Bacall have left gaping holes in the very soul of America’s entertainment industry. The sudden and shocking death of Williams, of course, left everyone in shock, but both figures represented the heights of 20th century American cultural history. Meanwhile, with multiple foreign policy headaches for the United States in Iraq, Syria, Gaza Strip, and Ukraine, Ebola outbreaks in West Africa, and a still-unresolved immigration crisis bringing thousands of unattended youngsters from Central America to the United States, the whole world seems to convulse in pain, outrage, and above all, sadness. And that’s not even taking into account horrendous stories that have received far less attention, both here and abroad.

As I attempted to comprehend the last week and also study for comprehensive exams (yes, it’s been quite

the week for me) my mind has wandered back in time, to 1974 and a certain famous—if not, in fact, infamous—article for Dissent magazine. Michael

Harrington’s essay, “A Collective Sadness,” spoke to a nation that just experienced the first ever resignation of its chief executive, and was struggling with the aftermath of defeat in Vietnam. The essay, in the Fall 1974 issue of Dissent, can also be seen as a lament for the American Left—a realization that no one seemed to have answers for the American people, least of all those who’d been struggling on a variety of political and cultural fronts for years. The following will pull from the version of the essay published in the book 50 Years of Dissent, based off the original Fall 1974 essay.

Harrington’s essay principally dealt with crises within the community of American Catholics, using them as a proxy to talk about the problems facing the nation as a whole. Harrington wrote, “People can’t believe in either God or their country the way they used to; people just don’t know what to believe in at all.”[1] He also acknowledged that America’s economic prowess that functioned to create a large middle class in the 1950s and 1960s had, by 1974, exhausted itself. But he noted that, unlike the Great Depression, the 1970s economic problems had “no clearly defined enemy as there was in the Great Depression,” showing that Harrington was well aware of how difficult it would be to push workers into a sustained, aggressive labor movement.[2] This wasn’t an indictment of the labor force, as much as it was a diagnosis of how much American politics and economics had changed so much since the start of the New Deal in the 1930s. It was also Harrington’s warning of the potential vacuum into which the New Right, still growing in power in the 1970s, would step into as the decade wore on and the Democratic Party (and, in essence, the American Left) failed to provide new strategies to respond to stagflation.

Harrington’s essay is an important one in understanding the American Left in the 1970s. In fact I’d go so far as to say it’s an excellent primer on the nation as a whole in the early 1970s. As Jefferson Cowie argued in Stayin’ Alive (where he has an entire chapter titled, “A Collective Sadness”), Harrington recognized that the Left no longer had an institutional liberal power base to push on issues such as labor and race.[3] The essay “A Collective Sadness” occurred to me time and again this week, not just in reference to the events of the 1970s chronicled by Cowie, but also due to our discussions about The Invisible Bridge, and debates we’ve recently had over the historiography of the 1970s and 1980s. However, it also speaks to me as a document that says, “Yes, this is when our modern era began.” An age where the Left seemed primed to take power in the aftermath of Watergate, but failed to achieve anything of substance for years to come; an age where conservatism triumphed at the national polls but, time and again in the 1980s, found itself divided between the Reagan/Bush White Houses and grassroots activists; and, finally, a divided nation finding it difficult to address the major issues of the day.

I remembered Harrington’s essay, in other words, because quite simply it seems to me that the nation once again suffers from a “collective sadness,” or, perhaps to be more precise, a “collective uncertainty.” Being a historian often means being able to take the long view of events. The good news is that you’re aware that things can get better. The bad news is that, well, you’re also aware that things can get much worse.

One final note: I’d considered devoting my post this week to thinking about intellectual history and the events in Ferguson, MO. To be honest, due to comps prep and being emotionally drained from observing what’s going on, I just couldn’t get something together in time. If I had, it would certainly have addressed civil rights memory and current debates over the “carceral state” and the militarization of American police.

However, I do have some links, books, and journal articles in mind, so if you’re interested in any of those topics, I have a few recommendations (and please, if you have more to add in the comments, feel free to do so):

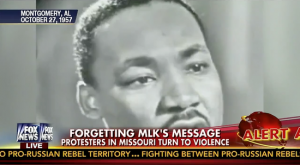

On Civil Rights Memory: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s essay, “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” from the Volume 91, Number 4, 2005 issue of the Journal of American History is still indispensable when considering how different groups of Americans remember the Civil Rights Movement. I’d argue this is important in considering responses to Ferguson from a variety of groups, and my post’s original content was going to be spurred by this image from Fox News’ coverage of the protests  and clashes in Ferguson.

and clashes in Ferguson.

Carceral State (a term used to refer to the large-scale prison apparatus current forming the backbone of the American criminal justice system): this is a topic that’s gained a lot of coverage in recent years, most notably in Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. However, another book has been released that shows the involvement of liberals in the early development of the current prison system in the U.S.—The First Civil Right by Naomi Murakawa. It’s a book I haven’t had a chance to check out but hope to do so soon. Also, The Condemnation of Blackness, as mentioned Friday night by Ray Haberski, is a great read on early 20th century views of crime and blackness. (For the implications of changing ideas of blackness and pathology in the academy, there’s always Daryl Scott’s Contempt and Pity.)

Police Militarization: of course, the most notable work is Radley Balko’s Rise of the Warrior Cop, which has received plenty of attention in the last week due to the police response to protests in Ferguson, MO.

On Ferguson itself: there’s plenty of good stuff on Ferguson (and I certainly expect folks in the comments to add more), but just to give some diverse flavor: there’s Jelani Cobb’s analysis on The New Yorker website; Charles C.W. Cooke’s analysis of how conservatives should think about Ferguson over at The National Review blog; Rembert Browne’s observations after spending several days in Ferguson; and, finally, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ brief thoughts on a particular element of the debate over Ferguson after being out of the loop for some time.

Check out those links, articles, and books for some historical context around what’s going on in Ferguson. And, as always, if you have more to add, please do so in the comments!

[1] Michael Harrington, “A Collective Sadness,” Fifty Years of Dissent, pgs. 111-119, quote on pg. 114.

[2] Harrington, pg. 117.

[3] Jefferson Cowie. Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class. New York: The New Press, 2010, p. 214.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

In this context, I think you’ve underplayed the importance of the Israel/Gaza problem: the collective faith problems of Catholics in the 70s are well-echoed in the communal self-examination and distancing happening in American Jewish circles this summer.

The images of Palestinians sending tear gas tips to Missourians, and activists in Ferguson with Palestinian flags, are part and parcel of the — dare I say it? — malaise that many of us are struggling with.

You know, I have to admit I didn’t even consider that angle. Very astute analysis!

And yeah, I’d have to agree that seeing Palestinians give tips to the residents of Ferguson, and the response of solidarity by some of the residents there is also part of the collective atmosphere–a “this can’t actually be happening here, can it?” attitude.

Robert, this is very beautiful and moving writing.

If I might add to the “carceral state” lit review (let’s say we were crafting a reading list for a community group seeking to make sense of Ferguson): I think the best way to go is longrange/chronological: so I might read chapters of Alex Lichtenstein’s book on the birth of the Georgia chain gang, David Oshinsky’s Worse Than Slavery, Robert Reps Perkinson on Texas prison empire… then Heather Ann Thompson on Attica and Ruth Wilson Gilmore on modern carceralism. Loic Wacquant’s essays on the matter are also considered essential (I will keep my comments on them to myself).

The broader point to which you draw attention, I think, is that what links 1974 and 2014 is the simultaneous presence of a “legitimation crisis” of the contemporary state and its current disciplinary apparatus (apologies for the jargon, but this is what it is)–as visible in the failure of the IDF to legitimate its Gaza incursion by way of anything other than “trust us/stand with us/the people we are brutalizing are worse than us/critique of Israel is Anti-Semitic” (the “just war” rationale, in other words, which does function effectively, from time to time, as a PR strategy, has been a total failure; the operation had to be affirmed as a police action); and in the similar failure of the Ferguson police/Jay Nixon to win consent on any terms other than: “we are in power/the threats of disorder outweigh commitments to democracy/do what we say and don’t ask questions.”

The current sadness, then–this overweening feeling, not of melancholy, but of grief–seems to go along with the current legitimation crisis. I wonder how they go together?

For New Leftists, the revelations of Watergate, the publication of the Pentagon Papers, etc. might have been expected to lead to happiness–“we weren’t crazy! our analysis of the system was correct, no matter how often our elders and opponents told us we were making it all up!”–but instead was a crushing blow, a disaster, even. I might put this in stronger terms: the surprise (and paradox) of the 1970s was that the Left never recovered from the shock of the “legitimation crisis’ that the Left itself had been describing for over a decade.

The stakes are considerably different, of course, in Ferguson, where the current legitimation crisis reveals a public secret that white Americans have not wanted to acknowledge.

Thus, I might propose that within the collective mourning for this lost son of this community, and for so many other lost sons and daughters across the country, there is also discernible (I hesitate to write this, because it could so easily be misconstrued) a certain joy–a political joy–which derives from a limit finally standing up to block the system’s endless capacity to lie, to narrate its own virtue in alternating tones of self-aggrandizement and self-pity; and from new technological means through which the ordinary people of the world can express solidarity with the ordinary people of Ferguson.

This is not to put the standard liberal “something good will come out of this” spin on the murder of Michael Brown–to do so would be obscene–but rather to stress that what we are seeing in Missouri is not *demoralization* (of the sort that Harrington sought to document)–in fact, what we are seeing, on the streets, in tweets, in open letters and essays, in all the ways the African American public sphere is talking back to the dutiful clerics of the status quo––strikes me as demoralization’s antonym.

First, thanks for the kind comments. And thanks so much for those recommendations on the carceral state–I was hoping someone would chime in with more, as I realized I was merely scratching the surface.

Your analysis of the legitimation crisis is spot on–and, I might add, the jargon here is needed because so much is going on that it’s difficult to otherwise describe accurately. I wrote about this essay because of what you described in your comment–and the gnawing sense that, the problems of the 1970s were either put on the backburner or have been ignored altogether. Of course, we don’t know how any of this turns out–but, with Chris Hayes (as an example) calling the post-9/11 era the “Age of Fail,” I can’t help but see a questioning of authority everywhere. This has been the case since the 1970s, but it’s being reflected once more across the American political spectrum.

Yes, thank you as ever Robert for a fantastic piece.

Re: legitimation crisis and carceral state scholarship, Stuart Hall and crew’s *Policing the Crisis* remains an essential text to return to ever more to think through how primary definers are able to capture and control media discourse and narratives. The cracking of this seems to be a key part of what Kurt’s pointing to about the “political joy.”

On separate point, I wonder how we locate the 94th Congress in the above story. I really don’t think we can underestimate how effective President Ford used the veto power to crush legislative efforts to ameliorate stagflation’s impact on working and workless people. It would be interesting to go back and see what Harrington and his crew made of that brief moment of legislative possibility.

Robert,

Thanks for this insightful post and for drawing attention to Harrington’s article.

I think Kurt’s reference to legitimation crisis is apt and highlights some paradoxes. Considered from one angle, the fact of Nixon’s resignation might have been seen (and probably was seen in some quarters) as a triumph of the American constitutional system. A President who covered up crimes and obstructed justice left peacefully rather than face an impeachment trial. Nixon’s personal instability, which might have led him to consider desperate, extra-legal measures to stay in power (a coup, e.g.), was trumped in the end by a reality principle (and perhaps some residual sense of responsibility). At least in theory, the way Watergate ended should have, despite various loose ends, reinforced the state’s legitimacy rather than undermining it.

That’s not, of course, how things worked out. We’re familiar with polls showing, in the decades since, a fairly steady decline in the number of Americans saying they have trust in government and other major institutions. The reasons for that probably have to do with cultural shifts as well as the institutions’ failures to cope with problems. Nonetheless, a political system that seemed at the time to have emerged from Watergate more or less intact, and to have at least temporarily repressed or buried the Vietnam trauma, proved mostly unable to anticipate and cope well with structural changes in the U.S. and global economy, changes that had their roots in developments of the late 60s and early 70s, when much of the immediate political attention was, understandably, focused elsewhere.

Although a narrative of unrelieved decline and crisis is too simplistic and one-sided, it would not be difficult, if one were so inclined, to construct one. The narrative would see a simmering ‘legitimation crisis’ since, well, pick a date (1974?) that has never disappeared, despite perhaps being in abeyance during parts of the Reagan and Clinton years. With liberal centrism (or centrist liberalism) weakened by the upheavals of the ’60s and with the Left unable to overcome internal divisions and programmatic disarray, the way was open for a resurgence of the Right against a backdrop of growing inequality, declining union strength, loss of well-paying manufacturing jobs, and the development of the carceral state. Although capitalism supposedly ‘recovered’ during the ’80s, helped by, among other things, a drop in the price of oil, the (alleged) recovery of capitalism (let alone the supposed ‘end of the business cycle’) did not prove to be very lasting.

nixon was trumped and done in by a coup himself; this one was designed by professionals. all else is part of the cover story.

the whole washington post saves america and its constitution by getting rid of the bad guy (yes, mr smith is back in washintgon, we hope you believe) was nothing more than a novel run in its pages and those of other major american media.

the real question of illegitimacy in government began in 1963 on an airplane in dallas with a wink of an eye.

@Harry Briscoe:

Obviously you subscribe to an elaborate conspiracy theory that I do not. The notion that Nixon “was done in by a coup himself” I view as a delusion (to put it politely). I’m not going to change your mind and you (absent presentation of some persuasive evidence, which in neither this comment nor a previous one along similar lines have you come close to offering) are not going to change mine. Nor are you likely, I would think, to find other takers for conspiracy theories here, though I can’t speak for anyone except myself.

P.s. Just to be clear, I’m also inclined to be very skeptical of conspiracy theories, especially intricate ones purporting to explain “everything,” that start with the JFK assassination, though I recognize that these will never go away.

As for clarity please remember that the government’s last official investigation (HSCA in the 1970s) found JFK to have been killed as the result of a conspiracy.

i’d wager your knowledge of deep political events doesn’t go much beyond the warren report or posner, which as we know are works of fiction.

au revoir

@H. Briscoe:

I’m aware (albeit in a general way) of the HSCA report. My recollection (which could be wrong) is that its conclusions were pretty much limited to the circumstances of the assassination itself, a matter on which I have no strong views. I’ll leave it at that.

David: thanks for the kind words. And yes, the relationship between Pres. Ford and Congress is something not talked about enough. The Congress that came to power in ’74 was an interesting animal, post-Watergate but in a time when the GOP was at it low point. I’ll definitely take a look at what Harrington and others thought during that era, because they had to have sensed there was some hope to get things done in Congress. And I’ll definitely check out the Stuart Hall piece.

Louis: Thanks again! Your observation about what Watergate meant to the American people is key–it’s been interpreted in both ways, as an affirmation of the American system and an indictment of it. The fact that it could be seen as both is, perhaps, indicative of how Americans have struggled with anxiety over their government–with no alternative in sight (for most people) where does the frustration with government go?