Black Internationalism as a Critique of U.S. Foreign Policy

By Sam Klug

Sam Klug is a graduate student in History at Harvard University, studying U.S. intellectual history in international perspective, with a secondary focus on the history of the modern Middle East.

Perry Anderson’s two-part piece on “American Foreign Policy and Its Thinkers” primarily dissects the trajectory of American foreign policy and the arguments of Washington’s foreign policy elites—some more perceptive than others, as his partial rehabilitation of the widely forgotten Nicholas Spykman illustrates. Though influenced by them, he does not spend a great deal of time examining the claims of the outright critics of the broader trajectory of the exercise of American military and economic power. At the same time, Anderson’s list at the end of his second essay, “Consilium,” identifies a number of such writers: “the names of Johnson, Bacevich, Layne, Calleo, not to speak of Kolko or Chomsky, are those to honor.” [1] We might add to Anderson’s list of contemporary critics, some of whom he rightfully identifies as the heirs to William Appleman Williams and his circle at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, another tradition of observers of America’s place in the world similarly inspired by a “genuine realism,” an “ability to look at realities without self-deception, and describe them without euphemism.” [2]

Perry Anderson’s two-part piece on “American Foreign Policy and Its Thinkers” primarily dissects the trajectory of American foreign policy and the arguments of Washington’s foreign policy elites—some more perceptive than others, as his partial rehabilitation of the widely forgotten Nicholas Spykman illustrates. Though influenced by them, he does not spend a great deal of time examining the claims of the outright critics of the broader trajectory of the exercise of American military and economic power. At the same time, Anderson’s list at the end of his second essay, “Consilium,” identifies a number of such writers: “the names of Johnson, Bacevich, Layne, Calleo, not to speak of Kolko or Chomsky, are those to honor.” [1] We might add to Anderson’s list of contemporary critics, some of whom he rightfully identifies as the heirs to William Appleman Williams and his circle at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, another tradition of observers of America’s place in the world similarly inspired by a “genuine realism,” an “ability to look at realities without self-deception, and describe them without euphemism.” [2]

This tradition, named by recent historians as “black internationalism,” contains a number of different strands. These include support for anticolonial movements (especially in Africa), expressions of solidarity with the peoples of the “darker nations” of the world, critiques of structural racism in government policy as it operates both within and beyond U.S. borders, opposition to the exercise of American corporate power abroad, and an understanding of American history in an imperial frame. Since it is not possible to give a full accounting of all (or even a few) of these different strands of a complex intellectual and political formation in this format, I will offer two snapshots of the black internationalist critique in the twentieth century—in the 1910s and the 1940s—and an example of the continued operation of racial hierarchy in U.S. foreign policy in the postwar period, even after the attempted cultivation of an anti-racist American image for foreign policy purposes. For their perceptive analysis of the prevalence of racial thinking in the extension of American power, the names of Du Bois and Padmore, not to speak of C. L. R. James and Malcolm X, surely are those to honor, too.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Americans thinking about international politics, and the burgeoning role of the United States therein, were obsessed with race. American government officials, intellectuals, and travelers exchanged theories and tactics with the more seasoned imperial administrators of the British Empire, forming a transatlantic dialogue on imperial management. As Paul Kramer has demonstrated, the racial ideology of “Anglo-Saxonism,” which centered around a vision of “Anglo-Saxons” (itself a hybrid, shifting category, but one that certainly excluded both African Americans and Filipinos) as a people uniquely suited to self-government and liberty, buttressed arguments within the U.S. in favor of the outright colonization of the Philippines. [3] “The sovereign tendencies of our race are organization and government,” wrote Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana in 1899. Defending the prospect of direct U.S. colonial rule over the Philippines, Beveridge excoriated those few Americans who believed that the commitment to self-government articulated in the Declaration of Independence ought to mean support for self-determination elsewhere. Rather, he expressed an exclusionary conception of the “capacity” for self-government, one that might resonate with American leaders from Woodrow Wilson to George W. Bush: “Ours is the blood of government; ours the heart of dominion; ours the brain and genius of administration.” [4]

At the same time as American officials were framing their ventures in racially exclusionary terms, scholars in the new field of “international relations” similarly understood race as a fundamental category in global politics. Writers in this field—often, tellingly, referred to as “imperial relations”—at the beginning of the twentieth century put more stock in what political scientist Robert Vitalis calls the world’s supposed “biological boundaries” than its geographic ones. [5] From academic supporters of the conquest of the Philippines like Franklin Giddings to its opponents, like John W. Burgess, the existence of biological racial distinctions, and a clear hierarchy among races, was undeniable. [6] While this fact may come as no surprise to students of the history of other social sciences in the United States, it stands in sharp contrast to the colorblind self-conception of international relations today, despite the overwhelming whiteness (and maleness) of the D.C. foreign policy community. The realist language that has come to dominate the way Americans understand and analyze foreign policy has involved the attempted erasure—or willful ignorance—of the prominence of racial thinking in the critical years of the early 20th century. If realism as a school of thought operates on the understanding that states pursue their material interests at all costs and that the balance of military force is the primary determinant of “success” or “failure” in the international arena, it ignores race and racism at its own peril. [7] Perry Anderson illuminates in his essays that the makers of American foreign policy, especially in the postwar years, have seen no necessary disjuncture between the good of the world and the good of American economic power—that ideology and the realism of power politics have gone hand in hand. Similarly, in the early twentieth century, foreign policymakers did not irrationally support racist practices at the expense of their true realist goals. Rather, they understood the maintenance and reproduction of racial hierarchies as central to their material interests.

W. E. B. Du Bois ranks among the earliest and best-known critics of the racism that contributed to the construction of global economic and political order in the twentieth century. Du Bois’ assertion in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) that “The problem of the twentieth-century is the problem of the color line—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea” has often been read as the starting point of a consciousness of race on a global scale. [8] A number of his other writings on race and international politics emphasized how this “problem” came to be. The hardening of international economic inequalities, through formal colonialism as well as American “dollar diplomacy,” also involved the production and regulation of difference among the peoples of the world. Writing in the midst of the First World War, Du Bois articulated this understanding of race as the product, rather than the progenitor, of racism:

W. E. B. Du Bois ranks among the earliest and best-known critics of the racism that contributed to the construction of global economic and political order in the twentieth century. Du Bois’ assertion in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) that “The problem of the twentieth-century is the problem of the color line—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea” has often been read as the starting point of a consciousness of race on a global scale. [8] A number of his other writings on race and international politics emphasized how this “problem” came to be. The hardening of international economic inequalities, through formal colonialism as well as American “dollar diplomacy,” also involved the production and regulation of difference among the peoples of the world. Writing in the midst of the First World War, Du Bois articulated this understanding of race as the product, rather than the progenitor, of racism:

That sinister traffic, on which the British Empire and the American Republic were largely built, cost black Africa no less than 100,000,000 souls, the wreckage of its political and social life, and left the continent in precisely that state of helplessness which invites aggression and exploitation. ‘Color’ became in the world’s thought synonymous with inferiority, ‘Negro’ lost its capitalization, and Africa was another name for bestiality and barbarism. [9]

Further, Du Bois identified racial hierarchies—on a global scale—as profitable. The age of colonial expansion that the First World War brought to a partial close was a tremendously lucrative one. “The ‘Color Line’ began to pay dividends,” Du Bois wrote; European and American racism was, among other things, an investment. [10]

In the 1940s, a vibrant black press and an outpouring of scholarly works by African American and African Caribbean writers insisted on the connections between Jim Crow, “informal” American imperialism, and outright colonial rule. Articulating what the contemporary philosopher Tommie Shelby defines as a “thin” basis of black solidarity—one constructed around “the unfinished project of achieving racial justice” rather than a common cultural identity—African American writers emphasized the commonalities between their own situation and the plight of colonized peoples. [11] In response to Winston Churchill’s exclusion of Britain’s colonial territories from the democratic promises of the Atlantic Charter, a Chicago Defender editorial noted that, just as “India [was] the victim of British imperialist greed, terror and rapacity,” both “Negro America” and “Puerto Rico” suffered from American versions of the same condition. [12] The black internationalist critique in the 1940s further extended to the placement of American military personnel and exercise of American economic power in formally independent nations. American-controlled sugar plantations in Puerto Rico and Cuba, and the one-crop economies they demanded, came under criticism, as did the scheme to turn Haiti into a center of rubber production in World War II after the fall of British-controlled Malaya to Japan. George Padmore, writing in the same period, warned against the “further tightening of the grip of international finance on Liberia” that might make the American tire and rubber company Firestone “the virtual ruler” of the West African state. [13] More than a decade before the New Left historians developed their understanding of a drive for open markets as the dominant force behind American foreign policy, black anticolonial writers, in forums designed for popular as well as scholarly audiences, had identified “informal” economic domination as the leading characteristic of the United States’ particular imperial formation.

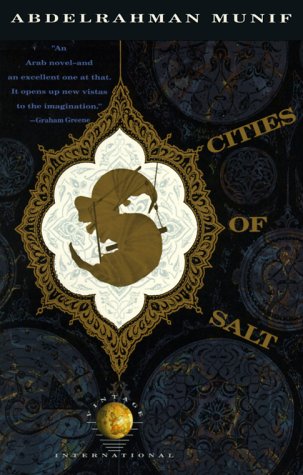

If foreign policymakers in the early twentieth century wore their racism proudly, Jim Crow became a problem for the international image of the United States at midcentury. As the United States positioned itself as the defender of freedom against the racist Nazi regime, political discourse and even mainstream popular culture began to recast racism as a particularly “un-American” social evil. The ethnic (and religious) heterogeneity of the United States became proof of its exceptionalism and a weapon in its “arsenal of democracy.” Further, as Mary Dudziak illustrates in her article, “Desegregation as a Cold War Imperative,” the shared desires of domesticating civil rights protest at home and removing a recruitment tool for the Soviet Union and its allies motivated the State Department to endorse desegregation for the sake of America’s image abroad. [14] Yet the construction and maintenance of racial hierarchies continued to play a role in exercises of American power abroad, just as it did in the organization of economic and social life at home.  The operation of the ARAMCO oil camp in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia for example, maintained segregated housing, differential access to services, and racially discriminatory wages, from the camp’s founding in the 1930s through the 1970s, encountering resistance from Saudi workers at every stage. Despite the company’s and the State Department’s promotion of the camp as a “modern day development mission” or a “private Marshall or Point Four plan,” the Saudi novelist Abdelrahman Munif captured the situation in his 1984 novel Cities of Salt:

The operation of the ARAMCO oil camp in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia for example, maintained segregated housing, differential access to services, and racially discriminatory wages, from the camp’s founding in the 1930s through the 1970s, encountering resistance from Saudi workers at every stage. Despite the company’s and the State Department’s promotion of the camp as a “modern day development mission” or a “private Marshall or Point Four plan,” the Saudi novelist Abdelrahman Munif captured the situation in his 1984 novel Cities of Salt:

The shift ended, and all the men drifted home to the two sectors like streams coursing down a slope, one broad and one small, the Americans to their camp and the Arabs to theirs, the Americans to their swimming pool, where their racket could be heard in the nearby barracks behind the barbed wire. When silence fell, the workers guessed that the Americans had gone into their air-conditioned rooms whose thick curtains shut everything out: sunlight, dust, flies and Arabs. [15]

If black internationalists did not examine this specific exercise of racial hierarchy in one outpost of American imperial rule, the tradition they exemplify offers the means for understanding it. Recognizing that racial thinking operates differently in various national contexts and periods in American history does not require dispensing with the hard-won knowledge that the construction of racial hierarchies has long formed a crucial component of the strategy of empires. The Jim Crow regime of labor and housing instituted by ARAMCO in Dhahran resonates in the labor flows of the contemporary Gulf, where migrant laborers from South Asia—racialized and placed outside the potential boundaries of citizenship—live in segregated, squalid conditions, stripped of their mobility and granted no benefits of citizenship, as they construct lavish buildings for the benefit of American universities and the oligarchy of global football.

Further, recent U.S. history demands the sort of interconnected analysis that the black internationalist tradition inspired. Federal investments in the “Sun Belt” over the past fifty years have both facilitated a massive wealth transfer to the white elite in the southern U.S. and structured large segments of the regional economy around the military and military-related industries. [16] These same investments have enabled the expansion of American military power over more and more of the third world, underwriting both a global network of military bases and violent campaigns in Vietnam, Panama, Afghanistan, and Iraq, among others. Considering the global circuits of destructive physical capital—from tear gas canisters to missile defense systems—can we really insist on a firm division between the “inside” and the “outside” of American state power? A left critique of foreign policy must contest the walling off of foreign policy as a separate sphere of politics. For the idea that the forces that structure the U.S. and the “rest of the world” share nothing in common is a fiction.

[1] Perry Anderson, “Consilium,” New Left Review 83 (Sept.-Oct. 2013), 167.

[2] Anderson, “Consilium,” 167.

[3] Paul Kramer, “Empires, Exceptions, and Anglo-Saxons: Race and Rule between the British and United States Empires, 1880-1910,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 88, No. 4 (March 2002), 1315-1353.

[4] Kramer, “Empires, Exceptions, and Anglo-Saxons,” 1332.

[5] Robert Vitalis, “The Noble American Science of Imperial Relations and Its Laws of Race Development,” Comparative Studies in Society and History Vol. 52, No. 4 (2010), 911.

[6] Vitalis, “Noble American Science,” 916-924.

[7] Robert Vitalis, Robert Vitalis, “The Graceful and Generous Liberal Gesture: Making Racism Invisible in American International Relations,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 29 (June 2000), 331-356.

[8] W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (New York: Dover, 1994), 9.

[9] W. E. B. Du Bois, “The African Roots of War,” 708.

[10] Du Bois, “The African Roots of War,” 708.

[11] Tommie Shelby, We Who Are Dark: The Philosophical Foundations of Black Solidarity (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005).

[12] Quoted in Penny M. Von Eschen, Race against Empire: Black Americans and Anticolonialism, 1937-1957 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997), 35.

[13] Quoted in Von Eschen, Race against Empire, 38-39.

[14] Mary Dudziak, “Desegregation as a Cold War Imperative,” Stanford Law Review 41 (Nov. 1988), 61-120.

[15] Robert Vitalis, America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (New York: Verso, 2009), 120; Abdelrahman Munif, Cities of Salt

, trans. Peter Theroux (New York: Vintage International, 1987), 391.

[16] See, for example, Nancy MacLean, “Southern Dominance in Borrowed Language: The Regional Origins of Neoliberalism,” in Jane L. Collins, Micaela di Leonardo, and Brett Williams, eds., New Landscapes of Inequality: Neoliberalism and the Erosion of Democracy in America.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

There’s a lot to absorb in this very good piece, so I know I’ll be giving it a second reading. A couple of quick reactions.

First, “the prominence of racial thinking” in the international-relations branch of political science as it developed in the U.S. from the early 20th century, while still insufficiently appreciated, is coming to be more widely recognized. In addition to the work of Vitalis and others whom you cite, there is for example S. Vucetic’s recent The Anglosphere (which I haven’t read yet). Might mention too some earlier work by Brian Schmidt (on the disciplinary history of IR in the U.S. and the importance of the study of colonial administration) and also Roxanne Doty (on, among other things, images of the Philippines in the U.S.).

Second, I found your discussion of black internationalism in the 1940s especially interesting. I’m reminded that the founding documents of the UN didn’t mention self-determination for colonies (DuBois was one of the few who criticized this silence). Mark Mazower, No Enchanted Palace, is revealing on that; also on the role of Jan Smuts in drafting the preamble to the UN Charter and the fact that Smuts and some others hoped the UN would be a means of preserving colonialism.

This was a wonderful analysis. The position of Black internationalism against mainstream American foreign policy currents is very important for historians to take stock of, as we continue to explore the intersection of US foreign and domestic policies, not to mention the “local” and “global” intellectual currents important to many African American activists.

The section you have on the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the racial hierarchy in the ARAMCO camps reminds me of the book by Sohail Daulatzai, “Black Star and Crescent Moon.” There, Daulatzai examines the relationship between African Americans and the idea of a “Muslim International” in the second half of the 20th century. He gets at this through both activists such as Malcolm X, and popular culture books and music (especially hip hop). But your work here also shows definite links between African American activists and US policies in the Middle East.

Two quick final responses(and there’s so much to talk about here): the turn against King for his anti-war stance in 1967 is a reminder of how little most mainstream commentators took seriously the Black internationalism concept. Most saw King as being “merely” a Civil Rights leader, and failed to understand how he (and probably others, from Malcolm X to John Lewis to Stokely Carmichael) would dare to tie problems at home to those abroad. Also, when thinking of Black internationalism, we’d be well-served to consider how other nations looked at the issue of Civil Rights in the U.S. The short, but valuable, book “Malcolm X at Oxford Union” by Saladin Ambar makes this point, showing how the British and, to an extent, the French governments viewed America’s racial problems in the 1960s. For Britain especially, they looked to the US for solutions to their own growing racial problems at home, tied to the end of colonialism. In some sense, we could consider how the US, Britain, and France were all responding to Black internationalism during the Cold War to, once again, think about how the local and global intersected often in the 20th century (and still do today).

Louis,

Thanks very much for your engaging comment. I, of course, learned a great deal from your post earlier in the roundtable!

Vucetic’s book looks fascinating, I had not encountered it before. I’m especially intrigued that it covers such a long time period, including the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War. Locating the origins of the UK-US “special relationship” in the earlier idiom of Anglo-Saxonism does not seem like too much of a stretch, but I would be interested to see how he thinks the “Anglosphere” has adapted to (or shaped) changes in both racial ideology and the dominant form of the state across the 20th century.

No Enchanted Palace is a terrific book. Carol Anderson’s Eyes Off the Prize provides a lot of detail on the efforts made by black Americans in the 1940s and 1950s to turn the UN into a body that might provide them some form of justice or at least serve as a forum to place the abuses of Jim Crow before the eyes of the world. She makes the provocative claim that Eleanor Roosevelt and other U.S. officials worked hard to give national sovereignty pride of place among the values of the new UN because they had one eye on protecting the “sub-national sovereignty” of the U.S. South. I had a section on this moment in the post, which I took out for reasons of space, but it’s fascinating. Malcolm X and others were advocating for stronger human rights provisions in the early years of the UN, which the U.S. was resisting — this before, of course, human rights became the favored language of American interventionism, and national sovereignty became an obstacle it had to overcome.

Sam,

Thanks — Eyes Off the Prize sounds both interesting and necessary to complement No Enchanted Palace which, as you know, doesn’t go into detail at all on black Americans and the UN; Mazower’s focus is elsewhere (he mentions DuBois but that’s about it, as I recall).

The Vucetic book I haven’t read, but given its apparent focus on the roots and history of ‘the special relationship’, I guess it’s not *directly* on point for the intellectual/disciplinary history of IR/political science. It was the race theme that led me to mention it. Brian Schmidt’s The Political Discourse of Anarchy (1998) discusses figures such as John Burgess and the development of IR in the U.S. (not developments outside the U.S., however). The word “race” doesn’t appear in Schmidt’s index, which is a bit odd, but I gather Vitalis et al. have that aspect fairly well covered now.

Also, I meant to mention that I fully agree with your concluding point in the post about not walling off foreign policy as a separate sphere.

Oops — sorry about the mistake with the italics (I guess my html skills need work).

Robert,

Thank you as well — terrific suggestions! Daulatzai’s and Ambar’s books are going on my list.

Incorporating the perspectives of French (or Francophone) and British actors would add a lot to this story, especially in the context of the racial politics of decolonization. Fanon would surely be a crucial source there.

Indeed–we can’t escape Fanon! There’s another, longer book on the Malcolm X visit to Oxford coming out this fall: http://www.amazon.com/Night-Malcolm-Spoke-Oxford-Union/dp/0520279336/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1405801484&sr=8-2&keywords=malcolm+x+at+oxford+union I’m curious to see what it adds to new scholarship about the transatlantic relationships among Black international activists.

A fascinating piece, Sam. I’m curious after reading your essay where you would fit Harry Haywood and the Communist theory of black liberation as a national liberation struggle into this schema of black internationalism?