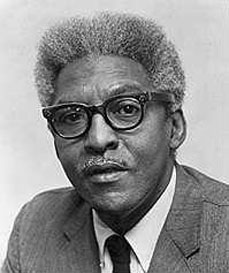

Bayard Rustin, the Black Left, and the Struggle Over Southern Africa in the 1970s

By the late 1970s, the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union reached a moment of renewed crisis. For  many conservatives the Jimmy Carter Administration had not done nearly enough to stem the tide of Communism in places such as Southern Africa. There, nations such as Angola, Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rhodesia and then, simply, Zimbabwe) and South Africa were all part of a dangerous game being played between the United States and its proxy forces in the region against Communist-backed insurgencies supported by the Eastern Bloc and Cuba. Southern Africa became a major debating point amongst American intellectuals in the late 1970s, as many conservatives, and quite a few liberals and leftists, began to worry that this was another sign of American weakness in the face of Communist aggression.

many conservatives the Jimmy Carter Administration had not done nearly enough to stem the tide of Communism in places such as Southern Africa. There, nations such as Angola, Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rhodesia and then, simply, Zimbabwe) and South Africa were all part of a dangerous game being played between the United States and its proxy forces in the region against Communist-backed insurgencies supported by the Eastern Bloc and Cuba. Southern Africa became a major debating point amongst American intellectuals in the late 1970s, as many conservatives, and quite a few liberals and leftists, began to worry that this was another sign of American weakness in the face of Communist aggression.

While the story of conservatives raising the alarm of American weakness in the 1970s is well-known, and the rise of neoconservatives around the same time has received serious documentation, fractures among African American intellectuals in this time period in relation to foreign policy are less well-documented. Such fractures, largely between Bayard Rustin and farther left African American intellectuals, offer a window into 1970s thinking about American foreign policy and its relationship to continued struggles at home over race and equality. At the same time, this brief study will take Perry Anderson’s work on American foreign policy and the Left and use it to evaluate the reasons for the rift between Rustin and other African American writers at places such as Black Scholar and Freedomways

. In short, the Black International that Sam Klug wrote so eloquently about yesterday was experiencing serious stress by the late 1970s. These stresses were, in many ways, leftovers from the rift between Rustin and prominent African American liberals on one side, and Martin Luther King, Jr. and leftists on the other over how address President Johnson and the Vietnam War in the late 1960s.

Perry Anderson’s series of essays on American domestic and foreign policies have provided a wonderful backdrop for our Roundtable so far. In particular, I’d bring your attention to the Anderson’s “Homeland” essay in the May-June 2013 issue of New Left Review. Anderson’s succinct analysis of American domestic politics since the early 20th century was a masterwork, but his section on the 1970s is what’s most important for this essay. Wrote Anderson, “Across the advanced capitalist world, the post-war boom came to an abrupt halt in the early seventies.” He went on to write, “The parameters of the political system shifted to the right everywhere in the West, but nowhere so far and with so little impediment as in the US.”[1] This was the world in which left activists were writing in during the 1970s, aware of both the limits of the left during the era, yet also aware that the fluctuations within the post-World War II economic and political order offered new alternatives to the Keynesian past. While conservatism in the United States and Great Britain would seize the political initiative by 1981, left intellectuals such as Michael Harrington, Bayard Rustin, and others did not see that as an automatic outcome during the tumult of the late 1970s. Their ideas, and the divisions between these camps on US foreign policy, constitute an important element of the history of the American Left.

As Klug noted yesterday, the Black International has long been a part of discourse in the West on the issue of foreign policy. Activists in the United States, Western Europe, West Africa, the Caribbean, and South America who have had some concern with Black freedom struggles have had to, throughout the 20th century, consider the power and image of the United States. American policy makers were aware of how the image of the United States could be both a blessing (through how the US promoted itself to the world) and a curse (due to how the Soviet Union and groups throughout the world antagonistic to American power could use violent images from the American South against the US). For my essay today I’ll focus exclusively on activists in the United States, and understand how African American activists found themselves on opposing sides of US foreign policy debates.

Debates over the Vietnam War loom large. As Daniel Lucks notes in his book, Selma to Saigon, “The contentious nature of the (Vietnam) war exacerbated preexisting tensions in the civil rights coalition along generational and ideological lines.”[2] For African American activists, debates over foreign policy were important areas of agreement, and sometimes bitter division. Activists operating in the Civil Rights Movement were well aware of the clamp down on dissent during the Second Red Scare of the 1940s and 1950s, an era seen by many scholars as being important to the idea of a “long civil rights movement.” While for scholars the era of the long civil rights movement—created by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall—stretches from the 1930s until the early 1970s, scholars such as Clarence Lang and Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua have criticized Hall’s argument on several grounds.

For our purposes, it’s important to zero in on their critique of how the Cold War affected the very nature of African American activism within the United States. Wrote Lang and Cha-Jua, “The continuous 1930s-1970s timeline theorized by Long Movement scholars ignores or minimizes the ruptures and fractures that the early Cold War and the FBI-coordinated counterintelligence campaigns of the late 1960s and early 1970s had on postwar black freedom struggles.”[3] And as Lucks and others point out, “This proximity to the Red scare, combined with the Cold War ethos, which too often conflated dissent from American foreign policy with communism, left an imprint on many veterans of the struggle for racial justice, including Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young Jr., and even longtime pacifist Bayard Rustin.”[4]

Splits between the NAACP leadership such as Roy Wilkins and other Cold War liberal African Americans, who remembered the late 1940s crackdown on the American Left (and especially, the African American Left), and left activists in the late 1960s constituted a serious rift during debates over the Vietnam War in the African American community. I argue that such rifts continued on into the late 1970s, with Bayard Rustin taking on other African American activists over Cold War-related crises in Southern Africa. Both groups interpreted events in Southern Africa in different ways: Rustin saw it as nothing more than continued Communist aggression that had to be stymied, while other African American intellectuals, committed to reconstituting the Black international ideal in the 1970s, saw the events in Southern Africa as indigenous forces fighting for self-determination against Western imperialism. Now it’s important to note that all the people involved here, whether they be Rustin or his radical opponents, wanted an end to Apartheid in South Africa. Disagreements over how to do so (Rustin favored engagement and limited sanctions, many others wanted larger and more damaging sanctions) were indicative of sharper disagreements over the fate of Southern Africa in the Cold War.

Splits amongst American socialists, as part of the broader American left must also be considered here. Rustin’s membership in the Socialist Party, and its rupture in 1972 between the Social Democrats USA and Michael Harrington’s Democratic Socialists of America over how to approach the Vietnam War, was an important symbol in larger rifts over foreign policy among American leftists in the 1970s. For Rustin and the SD group, a negotiated settlement for the war was best; for Harrington and other DSAers, immediate withdrawal was the only option.[5] However, while Vietnam served as the key litmus test for left activists in the early 1970s, some had already begun to turn towards Southern Africa and debate the conflict there between pro-Western and pro-Communist forces.

Perry Anderson’s “Imperium” essay gives a succinct analysis of the conflict between the US and the Soviet Union in Africa. The defeat of American-backed forces in Ethiopia and Angola in the 1970s “offered lessons in how better to run proxy wars” according to Anderson.[6] The collapse of détente in the late 1970s occurred not just in the mountains of Afghanistan, but also in the deserts of Ethiopia and the plains of Angola. Rustin believed that Southern Africa was a front in the Cold War the US could not afford to lose. Rustin, along with his colleague Carl Gershman (currently the President of the National Endowment for Democracy), argued in the pages of Commentary (and reprinted as a pamphlet for Social Democrats, USA) that defeat in Angola was a disaster for the United States.[7] “The victory of the pro-Soviet forces in Angola not only increased Africa’s vulnerability to a fate considerably worse than colonialism but, to a degree not yet fully appreciated, it also weakened the security of the West,” Rustin and Gershman wrote.[8] The two members of Social Democrats went on to tie the present issue of American weakness in Africa to American defeat in Vietnam. “The Angolan War showed up the failure of the United States to develop a sound African policy, or any African policy at all, and it exposed the total disorientation of American liberals, still reeling from the effects of Vietnam.”[9]

Rustin and Gershman were critical of American liberals in both Congress and the press. They argued that “the ‘central’ lesson” learned by liberals since Vietnam was “Soviet policies do not threaten the basic interests of the United States, and that in the final analysis, the U.S. offers the greater threat to world peace.”[10] For some of the radical writers of publications such as Freedomways, such an analysis of world affairs was not off the mark. Freedomways, a nexus of radical black writers and scholars from 1961 until it ceased publication in 1985, offered an intellectual haven for those how wanted to continue the black international tradition that Klug wrote about yesterday.

For example, in 1971 William J. Pomeroy, a member of the Communist Party who joined guerrillas in the Philippines who warred against the American-backed government there, wrote about the stakes of fighting Apartheid in South Africa. For him and many other activists on the left, South Africa’s Apartheid regime was part and parcel of the continued interference in Southern Africa by the West. Furthermore, for Pomeroy and others, racism at home was linked to American foreign policy actions abroad that, in the view of Freedomways readers, ran counter to efforts at self-determination by black Africans in South Africa, Zimbabwe, and elsewhere. Introduced by J.H. O’Dell, associate editor for Freedomways, the magazine’s Third Quarter 1971 issue addressed the problem of South Africa in a black international context.

O’Dell argued that the US-South African relationship was “a kinship sealed in an economic relationship in which huge profits are guaranteed to U.S. corporations by the semi-slave labor of African workers”, and “a marriage clothed in the psychology of ‘white race supremacy,’ a kind of mass mental illness which has been carried to its logical (!) extremes in South Africa’s internal development as a police state.”[11] Pomeroy, meanwhile, hoped that efforts in South Africa, and in Southern Africa in general, would create a movement “as strong and effective as the movement in support of freedom from the Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian people and of their struggle against imperialist aggression.”[12]

Arguments over how African American intellectuals should view the situation in Southern Africa also occupied the writers of Black Scholar. By 1976, writers in that publication also linked the American defeat in Vietnam with American action in Southern Africa. Jean Damu, then a staff writer for People’s World

newspaper and also a one-time Director of Black Studies at Eastern New Mexico University, pointed out that US foreign policy was beginning to take new shape in places such as the Indian Ocean, where American forces could be a “military threat to the Soviet Union and the national liberation movements of South Asia, the Middle East, and South and East Africa.”[13] None of this can be divorced from events in South Africa in 1976, when several hundred black South African students were killed by the Apartheid regime in Soweto.

Such attitudes towards the conflicts in Southern Africa were only exacerbated during the Carter years. As shown above, Rustin and others were concerned by President Carter’s actions in the region. For those on the left, however, Carter and his UN Ambassador, civil rights activist and former Atlanta mayor Andrew Young, did little more than continue previous policies that weren’t tough enough on the Apartheid South African regime. As argued by Simon Stevens in “’From the Viewpoint of a Southern Governor’: The Carter Administration and Apartheid, 1977-1981,” the experience of both men in the Civil Rights Movement in the American South affected their actions when it came to Apartheid South  Africa.[14]

Africa.[14]

Divisions across the American Left in the face of crises in Southern Africa in the late 1970s are an important lesson for anyone wishing to grapple with the history of the American Left and US foreign policy. While the victory over Apartheid in South Africa is the event everyone remembers the most, it needs to be considered in context of a larger debate about Southern Africa and the Cold War. It’s no coincidence that the debate over sanctions in the US began to swing decisively in favor of the program just as the Cold War between the US and the USSR was winding down in the late 1980s. Perry Anderson’s work is also a reminder of how domestic political pressures, and foreign policy debates among American intellectuals, are never far apart. That certainly wasn’t the case for Rustin and a whole host of African American intellectuals on the left.

[1] Perry Anderson, “Homeland,” New Left Review 81, May-June 2013, pg. 5-32, quotes on pgs. 9-10.

[2] Daniel Lucks, Selma to Saigon: The Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014, p. 3. It’s also worth noting here that Lucks presents his book, on pg. 2, as fixing a serious historiographic flaw in the study of the 1960s. “The interplay between these two great protest movements has not received the scholarly treatment it deserves. Indeed, there is a paucity of work on the relationship between the two.”

[3] Clarence Lang and Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua, “The Long Movement as Vampire: Temporal and Spatial Fallacies in Recent Black Freedom Studies,” Journal of African American History, Vol. 92, No. 2 (Spring 2007), p. 265-288, quote on pg. 271. On the domestic repression of Left civil rights activists in the 1940s, and the move of the NAACP and other organizations away from the black internationalist ideology, see Penny Von Eschen, Race Against Empire: Black Americans and Anticolonialism, 1937-1957, especially Chapter 7; Kimberly L. Philips, War! What is it Good For? Black Freedom Struggles and the U.S. Military from World War II to Iraq; Anticommunism and the African American Freedom Movement: “Another Side of the Story”, edited by Robbie Lieberman and Clarence Lang. Other key works in the field are, of course, Mary Dudziak’s Cold War Civil Rights and Thomas Borstelmann’s The Cold War and the Color Line. Finally, Brenda Gayle Plummer’s In Search of Power: African Americans in the Era of Decolonization, 1956-1974 speaks to the beginning of the era I’ve written about here. Plummer’s book considers the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power, and how both perceived American foreign policy.

[4] Lucks, p. 10. Nikhil Pal Singh also considers this era, and the impact of the Cold War on radical Black activists in Black is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy.

[5] Jervis Anderson, Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen. New York: HarperCollins, 1997, p. 336. This debate over Harrington’s stance on Vietnam, among other concerns about Harrington’s relationship with the American Left continues to this day, most recently in online debates about Harrington’s legacy as an American socialist.

[6] Perry Anderson, “Imperium,” New Left Review 83, September-October 2013, pg. 4-111, quote on pg. 75.

[7] It’s important to note that Carl Gershman was also an important figure in debates on the American Left over foreign policy. For example, he squared off with Michael Harrington in 1980 in the pages of Society over America’s stance against the Soviet Union.

[8] Bayard Rustin and Carl Gershman, “Africa, Soviet Imperialism, and the Retreat of American Power,” reprinted from Commentary, October 1977, Social Democrats, USA, pg. 2.

[9] Rustin and Gershman, pg. 2.

[10] Rustin and Gershman, pg. 5.

[11] J.H. O’Dell, “Introductory Comment to Section on South Africa,” Freedomways, Vol. 11, No. 3, p. 241.

[12] William Pomeroy, “The Resistance Movement Against Apartheid in South Africa,” Freedomways, Vol. 11, No. 3, p. 245.

[13] Jean Damu. “Southern Africa: From Angola to Soweto,” Black Scholar, Sept. 1976, p. 7.

[14] Simon Stevens, “’From the Viewpoint of a Southern Governor’: The Carter Administration and Apartheid, 1977-1981,” Diplomatic History, Vol. 36, No. 5, Nov. 2012, pp. 843-880.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Fantastic work, as ever, Robert! Thank you for this piece.

For those who didn’t live it, I think it can be hard to appreciate Rustin’s animosity to the CP/USSR from a place of being influenced by a Trotskyist-socialist critique, rather than a reactionary position. (At least, it was hard to wrap my mind around that.)

It’s interesting how the Communist vs. Socialist divide lurks in this piece in the form of O’Dell vs. Rustin. It also points to what each may have drawn from those respective movements. (Clearly O’Dell was more inclined to internationalism than to Stalinism.)

I found this interview with JO helpful in this respect:

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6927/

Thanks again for the wonderful contribution and digging into the messiness of Rustin’s politics/ ideas in the post-68 moment.

Thanks for the kind words, and also for that wonderful link. The divide on the American Left, especially when it came to the Soviet Union–is something we can’t forget. We have to always make sure to never lump in *everyone* on the “Left” as being for or against something. Foreign policy, especially that which was concerned with the Soviet Union, was no different.

There is of course also the prominent place of the South African Communist Party in the armed anti-apartheid struggle, which no doubt also fueled Rustin’s hostility to more radical alternatives.

Robert,

A nice post (and having lived through and formed political views during the 1970s, I esp. appreciated it).

This is a minor point with no real bearing on the substance of your post, but since you mention Harrington and Democratic Socialists of America: The group Harrington founded in the ’70s was called the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC). Democratic Socialists of America came into existence in the early ’80s; it was the result of a merger between DSOC and a group called the New American Movement (NAM). Both DSOC and NAM were quite tiny dots on the screen of American politics, but the merger probably did say something about the pressures faced by this part of the white Left in that period (I use the phrase ‘white Left’ because I don’t think African-Americans or Hispanics were a significant presence in either group; whereas DSA’s membership today is at least a little more diverse).

Thanks for that comment and you’re exactly right–it was DSOC in the beginning. There’s a wonderful essay about DSOC’s attempts in the 1970s to impact policy within the Democratic Party in the book “Making Sense of American Liberalism” called “Going Beyond the New Deal: Socialists and the Democratic Party in the 1970s” by Timothy Stanley. Admittedly I only referred to them as DSA from the start for the sake of convenience, but the history you mention above is also important to understanding the history of the American Left in this era.

Thanks for the reference to that Timothy Stanley piece; I’ll have to take a look at it.

I became a DSOC member in (or around) 1974, when I was in 11th grade in high school. Was never a real activist, though; at most an occasional one. (OK, enough autobiography ;)).

Kit: Thanks for that comment. You’re exactly right as well. We need to consider that whenever thinking broadly about resistance movements in Southern Africa, and American attitudes towards them. The ways in which conservatives and liberals saw the question of Apartheid in the 1980s for example–where, broadly speaking, conservatives were much more concerned about those Communists than were liberals, who saw in South Africa a morality play around racial discrimination–was reflected in some of the rhetoric surrounding Mandela’s death last year. Furthermore, such divisions were, to an extent, reflected within the Left in the 1970s, with Rustin and others of his ilk certainly not happy about the role of Communists in the ANC and other organizations in Southern Africa.