The Past Is Not A Cold Dead Place: Perry Anderson, Genealogy, History

by Matthew D. Linton

Matthew D. Linton is a Doctoral Candidate in History at Brandeis University and an intellectual historian of the American university in the 20th century. His scholarly interests include the international history of the Cold War, Sino-American policy, American perceptions of Asia and Asian people, and how funding shapes intellectual production. His dissertation, Understanding the Mighty Empire: China Studies and Liberal Politics

, traces the development of university China studies and its relationship to the New Deal-style liberal politics between 1930 and 1980.

In his triptych of articles for The New Left Review – “Homeland”, “Imperium” and “Consilium” – Perry Anderson examines the rise of the current American neoliberal national security state. Anderson uses each article to tackle a different aspect of this rise: “Homeland” looks at domestic politics, “Imperium” at foreign policy, and “Consilium” at current mainstream academic thinking on US foreign policy. These articles, and “Imperium” in particular, are historically oriented. Anderson traces the creation and development of the national security state from the 19th century to the present day with special emphasis on the way the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson shaped US policy thinking about America’s place in the world. Anderson’s erudition and the breadth of his project is impressive. The further I read his NLR articles though, the more one question nagged at me: is this history?

In his triptych of articles for The New Left Review – “Homeland”, “Imperium” and “Consilium” – Perry Anderson examines the rise of the current American neoliberal national security state. Anderson uses each article to tackle a different aspect of this rise: “Homeland” looks at domestic politics, “Imperium” at foreign policy, and “Consilium” at current mainstream academic thinking on US foreign policy. These articles, and “Imperium” in particular, are historically oriented. Anderson traces the creation and development of the national security state from the 19th century to the present day with special emphasis on the way the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson shaped US policy thinking about America’s place in the world. Anderson’s erudition and the breadth of his project is impressive. The further I read his NLR articles though, the more one question nagged at me: is this history?

I believe Anderson is writing as a genealogist, not a historian. Since being adopted by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in the late 19th century, genealogy has been one of social criticism’s most powerful and versatile weapons. It is also an important corrective to the historian’s orientation toward objectivity and context. For the purposes of this article, I define genealogy as an archeology of knowledge interested in exposing incidents of knowledge/power as constructed with the hope of disrupting its application and affecting future change. In contrast to the historian, the genealogist Anderson’s aim is to show how the American neoliberal national security state developed from the Founding to the present. His hope is that by exposing the contours of American empire, it can be more effectively combatted. [1]

I believe Anderson is writing as a genealogist, not a historian. Since being adopted by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in the late 19th century, genealogy has been one of social criticism’s most powerful and versatile weapons. It is also an important corrective to the historian’s orientation toward objectivity and context. For the purposes of this article, I define genealogy as an archeology of knowledge interested in exposing incidents of knowledge/power as constructed with the hope of disrupting its application and affecting future change. In contrast to the historian, the genealogist Anderson’s aim is to show how the American neoliberal national security state developed from the Founding to the present. His hope is that by exposing the contours of American empire, it can be more effectively combatted. [1]

Friedrich Nietzsche developed the genealogical method in the 1870s. Genealogy’s inspiration was not historical. In his “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life” (1874), Nietzsche dismissed most historical thinking for its undue emphasis on presenting an objective past. Attempting to present an objective past denied human subjectivity and deadened life-giving lessons by diluting them with spurious contextualization and detail. [2] Instead, Nietzsche crafted his genealogical method by combining his training as a classical philologist with his interest in Charles Darwin’s ideas about evolution. His interest in the relevance of non-historical scholarship to genealogy is evinced by one of Nietzsche’s fundamental questions in On the Genealogy of Morals (1887): “What light does linguistics, and especially, the study of etymology, throw on the history of the evolution of moral concepts?” [3] Here both linguistics and evolutionary science play a crucial role in showing the development of Western morality and values. To Nietzsche, a virtue shared by linguistics and evolution is its rejection of objectivity.

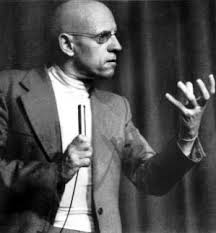

The culmination of Nietzsche’s genealogical method is found in Michel Foucault’s work on institutional power and authority. In his essay, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History”, Foucault provided a concise outline of his genealogical method and its indebtedness to Nietzsche. Foucault is explicit that genealogy is neither opposed to history nor is it a less rigorous version of it. “Genealogy does not oppose itself to history as the lofty and profound gaze of the philosopher might compare to the molelike perspective of the scholar,” Foucault wrote, “It opposes itself to the search for ‘origins’.” [4] Whereas Nietzsche used genealogy to undermine the foundations of Western morality, Foucault used the same method to unmask the power dynamics underlying institutions. His method was more historically oriented than Nietzsche’s, but in all of his genealogies (The Order of Things (1966), Discipline and Punish (1975), and The History of Sexuality (1976-84)) Foucault was committed to Nietzsche’s orientation toward the present and future at the expense of historical objectivity.

The culmination of Nietzsche’s genealogical method is found in Michel Foucault’s work on institutional power and authority. In his essay, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History”, Foucault provided a concise outline of his genealogical method and its indebtedness to Nietzsche. Foucault is explicit that genealogy is neither opposed to history nor is it a less rigorous version of it. “Genealogy does not oppose itself to history as the lofty and profound gaze of the philosopher might compare to the molelike perspective of the scholar,” Foucault wrote, “It opposes itself to the search for ‘origins’.” [4] Whereas Nietzsche used genealogy to undermine the foundations of Western morality, Foucault used the same method to unmask the power dynamics underlying institutions. His method was more historically oriented than Nietzsche’s, but in all of his genealogies (The Order of Things (1966), Discipline and Punish (1975), and The History of Sexuality (1976-84)) Foucault was committed to Nietzsche’s orientation toward the present and future at the expense of historical objectivity.

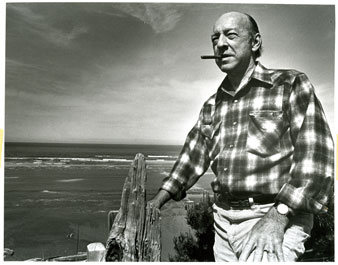

While Foucault was the most visible adopter of Nietzsche’s genealogical method, it also found an audience among American historians. These historians, including Gabriel Kolko and William Appleman Williams, believed that history should be used as a tool to criticize American culture, society, and politics. [5]  In the preface to his The Contours of American History, William Appleman Williams defined the purpose of history, it “is neither to by-pass and dismiss nor to pick and choose according to preconceived notions; rather it is a study of the past so that we can come back into our own time of troubles having shared with the men of the past their dilemmas, having learned from their experiences, having been buoyed up by their courage and creativeness and sobered by their shortsightedness and failures.”[ 6] Like Nietzsche, Williams believed history should be future oriented; it should inform us as we try to make a better future. Though history cannot be the sole means of informing a better future – in Williams’ words “History offers no answers per se, it only offers a way of encouraging men to use their minds to make their own history” – it can be a useful tool. [7] It should be a means of “enrichment and improvement through research and reflection,” not a backward-looking scholasticism myopically obsessed with the past for its own sake. [8]

In the preface to his The Contours of American History, William Appleman Williams defined the purpose of history, it “is neither to by-pass and dismiss nor to pick and choose according to preconceived notions; rather it is a study of the past so that we can come back into our own time of troubles having shared with the men of the past their dilemmas, having learned from their experiences, having been buoyed up by their courage and creativeness and sobered by their shortsightedness and failures.”[ 6] Like Nietzsche, Williams believed history should be future oriented; it should inform us as we try to make a better future. Though history cannot be the sole means of informing a better future – in Williams’ words “History offers no answers per se, it only offers a way of encouraging men to use their minds to make their own history” – it can be a useful tool. [7] It should be a means of “enrichment and improvement through research and reflection,” not a backward-looking scholasticism myopically obsessed with the past for its own sake. [8]

Beyond a common devotion to history for life, Nietzsche and Williams shared a commitment to using history as a tool to disrupt the search for singular origins, continuities, and wholes. Both reject the notion that total understanding of the past is possible. Perspective and subjectivity feature prominently in the work of both authors. In the same way Nietzsche could only create a genealogy of morals, Williams is limited to tracing the contours of American history. Nietzsche can trace a few common themes in his genealogy of morals: the rise of slave morality, the triumph of life-denying religion over life-loving warrior culture, and the coming of the übermenschen. Though Williams’ values could not be more dissimilar from Nietzsche’s, he also rejects a totalizing approach to history. Themes like frontier expansion, private property versus social property, and community are embodied in subjects like the Earl of Shaftesbury, Charles Beard, and Herbert Hoover. There are not impersonal historical forces for Williams, any historical continuities are dependent on individual agency for carriage between generations.

Perry Anderson is writing in the tradition begun with Nietzsche and carried on by Williams. Like Nietzsche and Williams, he is most interested in trying to understand how contemporary American domestic and foreign policy has come about. In line with his argument in “Homeland” that American political power has become unduly concentrated in the executive, Anderson embodies the characteristics of the neoliberal national security state in various Presidents. Woodrow Wilson in particular, is a pivotal figure for Anderson in unifying and arguing that, “Religion, capitalism, democracy, peace, and the might of the United States were one.” [9] It is no coincidence then for Anderson that, despite Wilson’s peace-loving rhetoric, he entered the United States into a world war that would massively expand American militarism at home and influence abroad. For Anderson despite periods of isolationism, “the ideology of national security, US-style was inherently expansionist.” [10]

Anderson’s vision of American foreign policy is erudite, but has clear limits. He’s not particularly interested in context or depth. To cover such a rangy topic as American foreign policy over a century’s duration in only a couple hundred pages compels Anderson to narrowly focus on a few individuals. He is also not concerned with counter-evidence or providing alternative opinions to his own. Like other genealogists, Anderson’s argument is polemical. While discussing the aims of the Truman administration after World War II, for example, Anderson focuses only on Europe. [11] The American government’s occupation of Japan, attempt to arbitrate the formation of a coalition government between the Chinese Communist Party and the Guomindang, and decolonization in South and Southeast Asia are omitted from Anderson’s account of postwar American policy. This omission streamlines Anderson’s argument regarding the expansion of executive power and political consensus regarding liberalism (in both its political and economic forms) across the world. The postwar reality was much messier. Congressional support for Chiang Kai-shek frustrated Truman and the State Department, opinion was divided as to the future of Southeast Asian independence movements with substantial support in the State Department for independent (even if leftist) nationalist regimes in Vietnam and Indonesia, and despite the surprising ease of US occupation in Japan, the future role of the US there was unclear. While not acknowledging these seminal events in US history would be a mortal sin if committed by a historian seeking to write an authoritative historical account of 20th century US foreign policy, providing this historical context is not important for realizing Anderson’s aims as a genealogist. Like Williams before him, Anderson is able to keep his argument focused and coherent by eschewing historical complexity.

Despite being interested in the past, Anderson rejects the methodological dogmas of the professional historian. Though Anderson is writing during a more methodologically inclusive period of post-linguistic, post-cultural turn historical scholarship, historians still prize values that Nietzsche criticized. Objectivity, now seen as a ‘noble dream’ instead of realizable goal by historians, nevertheless remains a valued mindset. Polemics and jeremiads, while useful fodder for historical articles and monographs, fall outside the bounds of acceptable historical scholarship. Many historians also continue to believe that history should be solely concerned with the past. Jill Lepore and other who have deigned to approach history with an eye to the present have been labeled “presentist” by their peers. [12] Frequently, these accusations amount to little more than political disagreement couched in the language of good scholarship. Still, they posit a hard, artificial dividing line between the past and present.

Genealogy provides an alternative to endless debates about historical methodology. It is a separate method with its own values. At the same time, it can inform our thinking about the past and its relevance to present and future events. Historians need not have a monopoly on the past. History can tell us about the past as it was and for its own sake. The genealogist is first and foremost a social critic, interested in history as a means of interpreting the present. Both are necessary for a complete understanding of the past and how it informs current events. Embracing methodological diversity will allow scholars, be they historians or genealogists, to construct a thoroughgoing and socially responsible vision of the past that can inform how we live in the present.

Genealogy provides an alternative to endless debates about historical methodology. It is a separate method with its own values. At the same time, it can inform our thinking about the past and its relevance to present and future events. Historians need not have a monopoly on the past. History can tell us about the past as it was and for its own sake. The genealogist is first and foremost a social critic, interested in history as a means of interpreting the present. Both are necessary for a complete understanding of the past and how it informs current events. Embracing methodological diversity will allow scholars, be they historians or genealogists, to construct a thoroughgoing and socially responsible vision of the past that can inform how we live in the present.

[1] Anderson, “Imperium”, 4.

[2] Michel Foucault wrote about Nietzsche’s criticism of objective history that, “The objectivity of historians inverts the relationships of will and knowledge and it is, in the same stroke, a necessary belief in providence, in final causes and teleology – the beliefs that place the historian in the family of ascetics.” The historians obedience to unchanging, dead facts denies, for Nietzsche, the perspectivalism of our understanding of past events as well as the historian’s own subjectivity. Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History” in Paul Rabinow (ed.) The Foucault Reader (New York City: Pantheon Books, 1984): 76-100.

[3] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals in Walter Kaufman (ed.), Basic Writings of Nietzsche (New York City: The Modern Library, 1992): 491. Italics Nietzsche’s.

[4] Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History”, 77.

[5] It should be noted that the genealogical method is not the exclusive purview of leftist social critics. I think the best way to understand much of Christopher Lasch’s late-career work is as genealogy instead of history. The Lasch monograph best fitting the genealogical description is The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics (1991).

[6] William Appleman Williams, The Contours of American History (New York City: New Viewpoints, 1961): 23.

[7] Williams, Contours of American History, 480.

[8] Williams, Contours of American History, 23.

[9] Anderson, “Imperium”, 9.

[10] Anderson, “Imperium”, 30.

[11] Anderson, “Imperium”, 17-18.

[12] This is obviously not a new phenomenon. American communist historians in the mid-20th century were often labeled unscholarly for viewing history as a tool for political struggle. My reference to Jill Lepore concerns a 2011 spat between her and Gordon Wood concerning her book The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle over American History (2011). See Gordon Wood, “No Thanks For the Memories”, The New York Review of Books (January 13, 2011): http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/jan/13/no-thanks-memories/ and Claire Potter’s thoughtful riposte at The Chronicle of Higher Education: http://chronicle.com/blognetwork/tenuredradical/2011/01/department-of-snark-or-who-put-tack-on/. David Sehat has written on the debate for the S-USIH blog back in 2011. See his post here: https://s-usih.org/2011/01/wood-on-lepore-on-presentism-or-why.html.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this very valuable piece.

I think that “genealogy” is a productive term with which to think about Anderson’s writing, but I also think that “genealogy” and “historiography” are less opposed, one to the other, than you present them here.

The category I would want to introduce is “event,” and to insist that Anderson wants to think about history as a sequence of “events,” as does Foucault, as does Nietzsche.

Perhaps we might say that a genealogy-with-events is historical, and a genealogy-without-events is not historical?

We might also distinguish between history-with-events and history-without-events.

The strong anti-“event” historiographical bloc would consist of the various “this happened, and then that happened” historians of various stripes; and certain French scholars who re-set the scale of historiography so that events disappeared (Braudel is the obvious “left” example here; Furet the obvious “right” one).

But Anderson, a Gramscian through and through, wants to understand “events,” particularly those that cause ruptures and bring about new conjunctures (and particularly those that happen in intellectual life/discourse).

Again, I would argue that he shares this in common with many in the Nietzschean tradition, like Foucault–at least the Foucault of Order of Things, Discipline and Punish, History of Sexuality, Birth of Biopolitics, etc.

The text that strikes me as crucial, in all of this, is Genealogy of Morals–more so than any other, this is where Nietzsche really does history. GofMs is also a book about a series of events–what makes it genealogical, perhaps, is that it is topological rather than linear (that is, it includes the “third” dimension of filiation: it begins with the premise that our ability to understand history is limited by the accumulated epistemological damage done by that very history, just as our ability to, say, come up with a true portrait of our parents would be hampered by the fact that we are their children).

What Nietzsche really wants to explore in GofM is the history of the “ascetic ideal” and, in particular, its mobilization by the Christian priest. This is so much the case that Deleuze describes the book as “inventing the concept of the priest.” Of course, on one level, this is ridiculous–how can you invent the “concept of the priest” in the 19th century? On another, we understand what Deleuze means.

I might argue that EP Thompson works in a similar way when he “invents the concept” of the “moral economy of the crowd” or that Du Bois works in a similar way when he describes the forgeries of history or the wages of whiteness in Black Reconstruction.

So, what excites me about this piece is that it opens up a conversation about “genealogy”/”historiography” that should definitely be continued.

Kurt,

I agree with much of your comment. I did not intend to insinuate that I believed there was a wide gulf between history and genealogy. On the contrary, I find the two methods quite complementary. History, with its emphasis on orientation towards the past and objectivity, struggles to be effective social criticism while staying within the bounds of the discipline. Genealogy does not share history’s disciplinary bounds is effective social criticism – when in the proper hands of course. Unfortunately, I’ve found genealogy spurned in circles of professional historians. Many seem to view it as a perversion of history, a less rigorous use of the historian’s tools for nakedly political purposes. Foucault goes to great lengths to dispel these misconceptions in “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History” and Discipline and Punish, but seemingly to no avail.

What I find interesting in On the Genealogy of Morals is the tension between Nietzsche’s genealogy and history. Though I agree that Nietzsche is operating as a historian, he goes to great lengths to argue that he is not writing a history of morality. Perhaps Nietzsche is simply being contrarian, but I think there’s more to it than that. Some of his discomfort with history is undoubtedly due to the rigidity of German history scholarship. I also think part of his animus against history has to do with his fears about its impact on human will. Nietzsche prizes creativity and in “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life” he expresses concern about the ways history can limit the horizons of human creativity. I think Nietzsche sees genealogy as a creative enterprise. Nietzsche does not want to interpret or understand the past, he wants to build a usable past for future greatness. In practice, Nietzsche’s genealogy does not look totally dissimilar from history (particularly as it’s practiced now), but I think Nietzsche intended genealogy to be a distinct method apart from history.

I really enjoyed this take on Anderson, as it brings up an under examined side of his thought. I do wonder how his Marxism relates to his genealogical take on history, and where does dialectical thinking fit in here.

I do concur with Kurt’s comment in regards to the opposition between genealogy and historiography. The questioning of objectivity as a discursive construction is not synonymous with the production of polemics or jeremiads, nor with the disregard for some form of truth value. In fact, after writing The Order of Things–better translated as Words and Things–Foucault was accused by some of his French colleagues for being…a positivist of all things! It is worth quoting in full his reply in The Archaeology of Knowledge to help us understand better his theoretical approach:

To describe a group of statements not as the closed, plethoric totality of a meaning, but as an incomplete, fragmented figure; to describe a group of statements not with reference to the interiority of an intention, a thought, or a subject, but in accordance with the dispersion of an exteriority; to describe a group of statements, in order to rediscover not the moment or the trace of their origin, but the specific forms of an accumulation, is certainly not to uncover an interpretation, to discover a foundation, or to free constituent acts; nor is it to decide on a rationality, or to embrace a teleology. It is to establish what I am quite willing to call a positivity. To analyse a discursive formation therefore is to deal with a group of verbal performances at the level of the statements and of the form of positivity that characterizes them; or, more briefly, it is to define the type of positivity of a discourse. If, by substituting the analysis of rarity for the search for totalities, the description of relations of exteriority for the theme of the transcendental foundation, the analysis of accumulations for the quest of the origin, one is a positivist, then I am quite happy to be one (p. 125).

Kahlil,

Sorry for the slow response. I too wondered about how genealogy fits into Anderson’s Marxism. When writing my master’s thesis on Karl Wittfogel, I became very interested in unilinear versus multilinear models of Marxist development. I wonder if genealogy might be compatible with a multilinear model of historical change. Just as there are many paths to undergoing development, I don’t see why Western Marxists like Anderson couldn’t accept genealogical approach to understanding historical change.

Regarding Foucault, I think it’s important to note how Foucault’s genealogy differs from Nietzsche’s. Nietzsche’s opposition to scholarly history is made explicit in “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life” and On the Genealogy of Morals, even if he is guilty of being more of a historian than he’s willing to acknowledge. I don’t find the same opposition to history in Foucault’s work. In my reading, Foucault views genealogy as one tool to get at specific types of questions about power and authority. He does not dismiss history out of hand, instead limiting its role. Foucault even flirted with history when writing his early work on madness, but ultimately seemed to settle on genealogy as a method of inquiry.

As I mentioned in my above comment to Kurt I do not see history and genealogy as opposing, but instead as complementary. My hope is that historians in the United States will take more seriously Nietzsche and Foucault’s genealogical work as a useful way of exploring the past. I think writers like Williams and Anderson give us examples of how borrowing from the genealogical tradition can add valuable insight to historical discussions, particularly of topics animating current events.

Gotcha, thanks for the response, Matthew. Taking into consideration your distinction between Nietzsche and Foucault, which seems quite valid, I would wonder then to what extent Anderson can be associated more with the former instead of the latter. This is of course linked to his conversations with the so-called poststructuralist trend of continental philosophy in the seventies–with Foucault at the forefront in terms of impact within historical inquiry. A key question would also be in what way does Anderson’s work differ from Foucaultian or Nietzschean genealogy. How, for example, does his “realism” work alongside his genealogical framework, or his emphasis on the relationship between economy and politics. In the end, like you point out, this question is about tracing multilinear models in Marxism, specially in the present. How does Anderson’s work compare to other contemporary Marxist historians? Thanks again for a wonderful post!

I think the question of influence on Anderson’s genealogical method is a good one. I’m not intimately familiar with Anderson’s corpus but I sense he’s more Foucauldian than Nietzschean. Anderson does not seem to have a particular animus against history. Like Foucault, he also does not presume to trace the origins of American empire instead vaguely alluding that they’re bound up with the birth of America itself. Anderson is much more concerned about the ways postwar national security free market liberalism has created the contemporary world order. With Nietzsche and Foucault, Anderson hopes to debunk the supposed naturalism of the current world order and its shape.

I think Anderson’s realism and the genealogical method can coexist comfortably. I see Anderson’s realism as a worldview, a way of understanding politics. Genealogy is a method, its function is more instrumental. In this case Anderson uses the genealogical method to espouse a realist worldview. It’s probably possible (though I have obviously not attempted this) to write a genealogy of American empire to espouse a federalist or post-realist worldview. Similarly, a realist picture may be created using tools other than genealogy. I’m sure the mathematical whiz kids in political science have ways of modeling realism in past and contemporary politics that look nothing like genealogy.

I’m not super in tune with contemporary Marxist historiography. My impression is that Marxism is currently fragmented across national and ideological lines, but someone like Kurt or others would know better than I.

The division of academic labor into the separate disciplines that are today labeled history, sociology, anthropology, political science, and economics is a product of the nineteenth century. (I know there have been historians since Herodotus or whoever, but I’m talking about the sharp disciplinary divisions.) These divisions do not correspond in any neat way to natural divisions in the world they study; in a word, the divisions are somewhat artificial. They allow professional scholars to organize themselves into guilds and associations, create standards for what constitutes good work, and distribute rewards and so on, but the divisions can also hamper inquiry. These points are probably obvious but nonetheless I think worth noting in a discussion that has partly revolved around the (alleged) characteristics of history (e.g., a valuing of objectivity, even if an unrealizable goal) vs. genealogy. Because all historians have to be selective in their evidence, one person’s historian might often be another’s genealogist. That said, I think a lot of Matthew’s points, e.g. re Anderson’s neglect of Asia, are well-taken. [see Immanuel Wallerstein et al., Open the Social Sciences, on the 19th-cent. origins of the current academic disciplinary dividing lines.]