(This post kicks off a multipart series by guest poster Kristoffer Smemo on the question of how one might historicize the aesthetic, affective, and political work of the Southern California hardcore punk band Black Flag. We are delighted to welcome Smemo, who is a PhD candidate in US History at UC Santa Barbara, and writing a dissertation on liberal Republicans and twentieth century labor politics).

My Rules, My War: Black Flag and American Working-Class Thought in the 1980s

In its early-1980s heyday, Los Angeles’ Black Flag seemed to be making the most anti-authoritarian music in America. Gripped by suburban boredom, kids from the idyllic beach communities lining LA’s southern coast made punk “hardcore”: drill sergeant barks, speed, noise. The surfers and skaters who packed Black Flag’s early, sweaty shows at rented Elks’ Lodges earned the enmity of vicious LA cops eager to stifle the same teen energies that once propelled the “riots” on the 1960s-era Hollywood Strip.

Under intense police harassment, the band lit out on long, grueling tours of the country they called “creepy crawls,” after the Manson Family’s brand of home invasion. Their music scored (as per the title of Penelope Spheeris’ scene documentary) “the decline of Western Civilization.” When the inevitable moral panic regarding “punk rock violence” gripped nightly newscasts and cautionary episodes of CHiPs and Quincy, Black Flag stood at the center of it all.

This is the familiar narrative of the ascent of Black Flag––and of American punk in general––popularized by journalist Michael Azerrad’s 2001 book Our Band Could Be Your Life. But such accounts fail to locate the ideological coordinates of bands like Black Flag—proponents of what I call anti-systemic working-class conservatism. Describing Black Flag’s aesthetic in these terms reveals much about how Black Flag’s sound and imagery stretched well beyond any standard description of “punk.”

On a day-to-day basis in the early 1980s, Black Flag engaged in what world systems theorists call “anti-systemic protest” against the ever-widening gyre of capitalist prerogatives by staging their own shows, squatting in abandoned property, tagging their iconic black bars everywhere, and otherwise disrupting the grinding gears of post-industrial capital.

But these acts of protest belied a much more conservative worldview. The band dug deep into the spectacle and sexual politics of ‘70s stadium hard rock, Charles Manson’s proletarian subversion of bourgeois hippie values, and a “do-it-yourself” ethos reminiscent of Jefferson’s idealized yeoman farmer. They complied this disparate assemblage to forge a politics of manly self-sufficiency at once repulsed by the plutocratic excesses of the Reagan era as much as the classed and raced contradictions that finally ate away the foundations of New Deal liberalism.

Plumbing Black Flag’s distinctly Southern California roots reveals much about the cultural decline of postwar liberalism—with its provisions for economic security and relative affluence for white workers—beyond the familiar confines of the Rust Belt. As a generation working people in the 1970s lost their foothold in LA beach communities amid the onslaughts of gentrification and privatization we now call neoliberalism, their children revolted. But Black Flag’s alternative effectively looked backward to the insular, self-sufficient communities of Tocqueville’s America, rebuilt on the rubble of a Keynesian mass production, mass consumption society.

Punk culture, as Greil Marcus insisted in his seminal book Lipstick Traces, was in love with ugliness. Its music, however, was often surprisingly catchy and tuneful—as in the bubble gum-flavored output of the Ramones. While the Ramones provided the template on which the teenage founders of Black Flag began to build their aesthetic project in 1976, the fledgling band was soon drawn to the exploration of more palpably ugly sonic textures.

Black Flag’s leader Greg Ginn (a UCLA economics major) wanted to play squalling guitar freakouts inspired by the Texas-born but longtime California resident free jazz giant Ornette Coleman. He wanted to wed that dissonance to the glossy stadium metal of Ronnie James Dio’s Black Sabbath and Ted Nugent. And, as was common in the new culture of capitalist/anti-authoritarian/countercultural entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley, Ginn was obsessed with the Grateful Dead.

The political economy of postwar Hermosa Beach, Black Flag’s hometown, made this peculiar mélange possible.

Ginn and the early members of the group all hailed from the suburban communities of southern California that first boomed as the terminus for wartime labor migrants, and continued thereafter to pull transplants into the far western corner of the Sunbelt. This world stretched southwards to the docks and naval facilities of San Pedro up into Long Beach. While Chester Himes (and later, Walter Mosley) had once mapped these territories as sites of black migration in the 1930s and 1940s, a process set in motion by the explosion of defense industry jobs, by the 1970s, as a result of processes of state-sponsored manipulation of the real estate market, the automation of the ports, the deindustrialization of South Central LA, and a racially discriminatory process that subjected many people of color to the agonies of “last hired, first fired,” these spaces had become predominantly “white working-class” in character.

They were also suburban spaces, connected to the rest of the sprawling metropolis by the dense of latticework of Eisenhower’s superhighways. By the mid-‘70s, Hermosa Beach kids could get to Hollywood to see some of the first West Coast punk acts, but also to the imposing Inglewood Forum to revel before Aerosmith and Alice Cooper. Along with the surf and sun that had inspired Brian Wilson in nearby Hawthorne, Hermosa Beach had once attracted nomadic Beats to its thriving jazz scene headquartered at the Lighthouse club.

As the Age of Reagan approached, the white working-class bohemia of Hermosa strained under the combined weight of deindustrialization and gentrification. Though never as reactionary as nearby Orange County—the navel of the John Birch Society—Hermosa maintained its own moderate conservatism that always looked askance at the postwar New Deal legacy (indeed Ginn’s parents, who many described as eccentric artists in their own right, identified as resolutely anticommunist Eisenhower Republicans). Here the enterprising spirit of small business went hand in hand with self-expression. As a young man Greg Ginn built his own thriving mail order company selling repurposed World War Two electronics surplus to HAM radio enthusiasts.

The avant-garde commitments cultivated by Ginn and Flag in Hermosa Beach, rested on an almost Toquevillean notion of independence and self-reliance. Mass culture provided a wealth of material from which to draw from and distort, but it also signified the crushing conformity and exploitation of a mass society, governed by an expansive set of interlocking corporations and government agencies. Black Flag looked backward, to an era of small producers hewing and building what they needed for themselves and their tight knit communities. Thus, Black Flag booked its own shows and created its own record label, SST, pioneering the “DIY” ethos so central to punk’s bona fides as a true counterculture.

In this sense Black Flag could relate to the hippies’ desire for authentic communitarianism and even the participatory democracy of the Students for a Democratic Society. But Black Flag’s alternative to corporate and neoliberal marginalization found expression not in a New Left revolutionary posture, but in a decidedly petit-bourgeois entrepreneurship. Black Flag’s work ethic became legendary. Incessant touring, marathon rehearsals, and ‘round-the-clock sweat and black coffee kept the SST label afloat—and burned out one band member after another.

Indeed, that image of relentless toil in virtual obscurity and amid grinding poverty and police harassment gave Black Flag’s sweated labor an aura of virtuousness. Ginn and those who followed him (and they followed or found themselves expelled) on one grueling tour by van after another earned their meager compensation, and earned it justly. Black Flag came to fetishize their lyrics’ themes of misery, paranoia, and isolation in their own lifestyle, one that thoroughly blurred any distinctions between work and self. By the mid-‘80s, increasingly augmented with marijuana and acid (used pragmatically to keep the driver of the van awake en route to the next gig), Black Flag’s music and image became laced with a darkly psychedelic rendering of Calvinism. The unmitigated virtue of work became a hallmark of the band’s conservatism, distinguishing sharply between them and us.

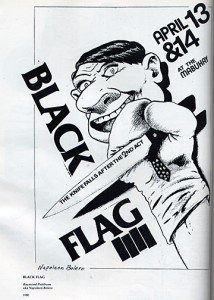

(We’ll take up the contours of Black Flag’s working-class conservatism further in next week’s installment by parsing out the vicious pen and ink artwork supplied by Ginn’s brother Raymond (whose illustrations of Charles Manson and the Weather Underground bore the nom du guerre Pettibon), and Flag associate Joe Carducci’s magnum opus on class in popular music,

Rock and the Pop Narcotic.)

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Fabulous post, welcome to the USIH blog Kristoffer! One thing I have always wondered about is the heterogeneous character of punk rock scenes across the globe. When I was a teenager I thought all punk was anarchist, and slowly learned how the affects and ideologies of punk rock are much more complicated than I had originally assumed. On the one hand, there were bands that explicitly identified with a radical leftist genealogy of critique and activism–in the US one could think of bands ranging from the Dead Kennedys in California and Fugazi in DC to Bikini Kill and the riot grrrl phenomenon. And on the other, a more reactionary strand that, beyond Black Flag, would include bands like The Misfits, X, The Descendants, etc. But it’s perhaps more interesting when it’s not so clean cut and one finds overlapping elements (for instance, the “fascist” spectacle of heteronormative masculinity some critics associate with punk aesthetics and the mosh pit, as exemplified by music critic Lester Bangs’ famous take down of the Kennedys). I really like how this post underscores the significance of region for grasping the singularity of bands such as Black Flag.

Race is brought up in connection to the history of Hermosa Beach; I would love to hear more about the politics of race in the world of SST and Black Flag. Punk rock has had its own complicated relationship with non-white difference, but at the same time I have always been fascinated by the fact that Black Flag had a Puerto Rican frontman in one of its versions and also a Latino drummer). Did these participants in the scene subvert the “white” working-class conservatism so wonderfully explained here?

Thanks so much for welcoming me in! And thanks too for prompting me to think more about the question of race and punk, which I’m hoping to get into more detail next week. The case of Ron Reyes and Robo I think is crucial for placing Black Flag’s particular critique of liberalism. Robo was forced out of the band and the country after a tour of England when US customs discovered he’d been living in the US on an expired student visa. And Reyes sang “White Minority,” a song that Ginn wrote with the intention of being a broad satire on racism and Manson’s own demented “Helter Skelter” vision of a race war apocalypse. Not mention they participated in an LA scene that included prominent Latino groups such as the Plugz or Suicidal Tendencies. So Flag did suggest a critique of the racial conservatism that Thomas Sugrue highlighted in working-class Detroit.

But these experiences also influenced Black Flag’s critique of Great Society liberalism as a failed elitist social engineering project. The horrifying scenario of “White Minority” implied that the legislation and protest of the ’60s could never overcome the deeply entrenched racism of American society. Indeed, much of Flag associate Joe Carducci’s book Rock and the Pop Narcotic denounces liberalism for its out of touch elitism that’s comparable to Paul Schrader’s George McGovern stand-in in Taxi Driver. Thanks again for the prompt, and I’m eager to take this up further.

Reading Kurt’s reply I also would like to hear a bit more about the distinction between working class conservatism and petit-bourgeois entrepeneurship. This made me think again of anarchism–when does it become conservative or entrepeneur-like? Was Black Flag actually an anarchist band and how would the labeling affect our understanding of both? Bringing back affect, I am also thinking of the importance of populism for punk rock. Again, looking forward to the next post!

Great post. I’m particularly taken with your way of using Black Flag to shine a light on certain understandings and constructions of self-approved work and labor here in the development of DIY punk and post punk after 1977 into the 80s. This, for instance, is ace: “Black Flag’s alternative to corporate and neoliberal marginalization found expression not in a New Left revolutionary posture, but in a decidedly petit-bourgeois entrepreneurship.” The notion of punk–and a lot of aspects of rock in general one could even say right back to the 50s, and across lines of race and ethnicity–as a petit-bourgeois cultural formation seems really important and surprisingly understudied. With punk, I’d argue, you can see a certain petit-bourgeois sensibility in play in NYC with the Ramones, in Detroit, Ohio cities, and in LA, among other locations.

I also love a “darkly psychedelic rendering of Calvinism”! That’s funny. I am picturing Christopher Lasch as a long lost member of the band. Maybe on one of those long-forgotten early 80s van tours that went through Rochester, NY.

Amazing post, I cannot wait to read more. I am very interested to hear what you have to say about “White Minority” and the question of police brutality.

Hardcore has always seemed to have an obsession with self-documentation. (There are several documentaries coming out this year on DC hardcore.) But this documentation has seemed to avoid, or even forestall, any deep analysis, especially class analysis.

Kahlil —

I agree with you that this is very important:

“the distinction between working class conservatism and petit-bourgeois entrepreneurship”

This strikes me as very crucial to thinking about the important transformations going on in the 1970s and 80s out of which and into which Black Flag arose and returned. They—wc conservatism and pb entrepreneurial ideals and practices—certainly intersected, but as constellations or conjunctions of contradictory impulses about equality, fairness, belonging, citizenship, justice, and questions of how culture, the state, and the market related to each other. None of it totally worked out, to be sure, in any fully coherent way, but more importantly felt and explored in the music and scene that Black Flag generated out of their art making, sounds, imagery, stylings, activities, and social relations.

MJK

Khalil and Michael,

I’m glad you both pointed to the prole. conservatism/petit bourgeois dynamic. I’m still trying to parse this out myself, but I think because Black Flag’s brand of anarchism was very much rooted in its intense producerism it thus became infused with a kind of authoritarianism. On the one hand their professed nihilism suggests a kind of Nestor Makhno-style anarchism, but on the other it’s a kind of Herrenvolk democracy where production earned a kind of citizenship denied to others. “Anarchy for me, tyranny for you,” as bassist Chuck Dukowski liked to say. I really appreciate the comments!

Christian,

Thanks for the heads about the DC docs. I’m on the case, too, to get more seriously into the politics of “White Minority” and police brutality.

Good stuff Kristoffer and all the commenters. I wrestled wtih these questions in my Kids of the Black Hole: Punk Rock in Postsuburban California.

I situate hardcore within the postsuburban environment of Southern California, particularly as it was developing for young people coming of age in the aftermath of the sixties. I attempt to use theories of everyday life to interpret hardcore punks’ identities, communities and relation to society.

In some ways I think Black Flag was not “representative” in that they were leaders who refused the position of leadership. No other band, however, was as influential at the time. I talk about their “apolitical politics and their staunch individualism” and their rejection of consumerism in favor of hard work – very much in the classic American vein you mention.

I couldn’t really nail down a class perspective to Black Flag; not sure if either working class conservatism or petit-bourgeois entrepreneurship exactly capture their perspective. I think the Minutemen’s “jamming econo” is similar, but more explicitly political – worth exploring more fully how they are similar and different.

Also worth exploring is how Black Flag and Southern California punk and hardcore compare to other scenes. Montgomery Wolf as a new book coming out looking at various scenes in the US. More work could be done by looking at, for example, Crass in England, or, even more important, the Bay Area scene – I would love to see some historical scholarship on pre-Gilman Bay Area punk and hardcore.

Dewar.

Hi Dewar,

Thanks so much for your comments and suggestions. The comparative angle would be a fascinating next step, and I’m eager to check out Wolf’s new book. I really appreciate you drawing the links between Black Flag’s work ethic and the Minutemen’s “jamming econo.” My sense is that the two approaches to self-sufficiency and frugality do reflect distinct class political positions. The Minutemen’s solidarity with the Central American Left and its Beefheart-damaged jazz I think best exemplify the long reach of the multicultural anti-fascism advanced by Carey McWilliams and the Southern California Popular Front in the 1930s-’40s. Black Flag’s “apolitical politics” in turn reflected the classic small-holding yeomen’s desire for independence above all else. This is a preliminary stab at an answer, and completely agree that it’s worth taking apart in more detail. Thanks again for the comments and insights!

Bringing the Minutemen into the conversation is extremely important I think to tracing the potential emergence of the type of pluralist white-working class identity Jefferson Cowie longs for in Stayin’ Alive. But I would be wary of drawing a distinction between Black Flag’s commitment to autonomy and the Minutemen’s internationalism. As D. Boon says at one point in We Jam Econo, their ideal was an America with “a band on every block, a club on every other block, and a label on every block after that.” But this tension between the small-holding independent producer and the spectacle of stadium rock, a style Mike Watt expressly opposed, definitely seems worth exploring.

My apologies, Andrew, for letting this really good point fall through the cracks. I think you’re right that the aesthetic difference on the legacy of stadium rock is the crucial marker of the political difference between the Minutemen and Black Flag. Ultimately it comes down to the fact, as you rightly point out, that the Minutemen took an explicit stand to make punk “whatever we made it to be.” With the brooding shirtless Rollins and the enigmatic guitarist Ginn, Flag copped Robert Plant/Jimmy Page dynamic to the letter and perhaps could have been a more sullen Van Halen.