Dear readers: The following is a guest post from Jonathan Wilson, a Ph.D. candidate in American intellectual history at Syracuse University, who regularly blogs at The Junto.

Here’s an old question: What’s the difference between intellectual history and social or cultural history? It’s a question about subject matter and methodology. More subtly, it’s also a question about political perspectives, models of causation, and the historian’s degree of elite-white-male-ness. More subtly still, it’s a question about academic hiring standards.

Working on a dissertation concerned with the early nineteenth century, I sometimes have a hard time bringing this question into focus. It doesn’t really fit my understanding of how intellectual life worked. I don’t think it’s a meaningless question. But I do think it assumes the existence of social conditions that did not define intellectual life in the early American republic.

In fact, it doesn’t seem consistent with how early-nineteenth-century Americans themselves understood their intellectual history.

As far as I can tell, the first systematic essay in the “intellectual history” of the United States, published under such a title, was printed in 1847. That’s when Rufus Wilmot Griswold, a New York editor now best remembered for scandalous behavior

in a feud with Edgar Allan Poe, published an anthology of The Prose Writers of America.

This book, a sort of sequel to Griswold’s Poets and Poetry of America

, presented short biographies and samples of work by famous American authors from Jonathan Edwards to Margaret Fuller. (Well, actually, it ended with the Boston essayist E. P. Whipple.) And it began with a 35-page essay on “The Intellectual History, Condition and Prospects of the Country.” This is the essay I’m calling the first U.S. intellectual history. [1]

Griswold was kind of a hack. But his anthology project was not entirely different, in its aims and format, from Capper’s and Hollinger’s American Intellectual Tradition. More than one-third of the pre-1847 authors included in the sixth edition of Capper and Hollinger were also included in Griswold’s book. (Excluding colonists and women, actually, it comes to almost half.)

***

When Griswold wrote his essay, the term intellectual history was not entirely new. But it was unusual, especially as a label for a form of historical writing—a type of literary product—rather than a topic upon which to reflect.

In 1755, in the preface to his Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson had referred in passing to “a kind of intellectual history” or “genealogy of sentiments” visible in how successive authors appropriated each other’s words. That may be the first use of the term in English, though I’d hesitate to call it a coinage. The term seems to have come into currency only in the early nineteenth century, and then mostly in connection with a whiggish vision of society in general. It usually referred to overall human or national mental evolution. [2]

An American deist moral philosopher, for example, had referred in 1801 to “a new era in the intellectual history of man.” Book reviews published in magazines in the 1820s had alluded to “the intellectual history of the human race,” “the civil and intellectual history of woman,” and “the immense domain of intellectual history.” Such texts do not seem to have conceived of intellectual history as a distinct field, or even necessarily a special topic, of scholarship. They simply had suggested that the human mind had perceptibly changed along with human political institutions. [3]

The term also seems to have started appearing in French around the same time. The French term had been used in similar ways. An 1826 review of a book on Spanish navigation, for example, had opened with musings on « l’histoire intellectuelle d’une nation » as a subject related to the history of science and invention. In 1832, Honoré de Balzac had written a metaphysical novel called L’Histoire intellectuelle de Louis Lambert; in this instance, “intellectual history” apparently had meant roughly the same thing as intellectual biography, except maybe with coming-of-age implications. An 1833 review of two monographs on ancient Roman literature had described them as presenting « l’histoire intellectuelle du grand peuple » of Rome, involving “all the branches of human knowledge, arts, and imagination.” [4]

Before Griswold’s essay, what may have been the most notable “intellectual history” published as such in English had come from an impoverished but indefatigable Catholic historian working in London. Samuel Astley Dunham’s Europe During the Middle Ages, published in four volumes in 1833 and 1834, included a volume dedicated primarily to the intellectual history of England. Dunham had approached that topic systematically in two long essays. His essay on the intellectual history of the Anglo-Saxons had covered their “arts of life,” including their calendar, cooking, architecture, and furniture; their vernacular and Latin literature; and their science, including mathematics and astronomy as well as “more intellectual sciences” like moral philosophy. His essay on the “religious and intellectual history” of medieval England had followed a similar pattern, though it put more emphasis on ecclesiastical institutions. [5]

Dunham ultimately had judged the Anglo-Saxons, except for a few distinguished churchmen, intellectually backward. But he had not implied that intellectual life was a realm of thought distinct from other literate expressions of culture. Anything written, any form of study, and perhaps any well-developed craft, seems to have been fair game for his intellectual history of the English nation.

***

Thirteen years later, Griswold’s intellectual history of the United States was similarly comprehensive. Thoroughly nationalistic, it celebrated the accomplishments of “the Anglo-Saxon race in the United States” in all “the fields of Investigation, Reflection, Imagination and Taste” during the nineteenth century. [6] The essay sorted American intellectual achievements into a list of categories comprising theology, history, oratory, political economy, jurisprudence, antiquities, mathematics and natural science, fiction, humor, essays, travel literature, poetry, drama, and graphic arts. In his discussion of each category, Griswold named authors and works that represented the country’s progress. Some fields, he readily conceded, had produced far more American fruit than others.

Evidently, Griswold’s primary concern was to prove that Americans, despite a late start, were catching up to their British cousins in matters of creativity. He also wrote to urge Americans to write essentially American literature, not imitate European models. By so doing, he argued, American authors would elevate the spirit of the entire human race.

Indeed, Griswold made a very bold claim about his country’s intellectual life. He asserted that the United States was, intellectually, the world’s first post-national nation. Global communication and “the extending and deepening power of the press,” he wrote, were “rapidly subverting the chief national distinctions, and preparing the way perhaps for the realization of Goethe’s idea of a Literature of the World.” Although such a universal human culture was far off, “the New Civilization, of which our fathers were the apostles, is first to be universally diffused.” In other words, the United States was the first nation to allow its own community to develop a free and universal human culture. Here, private judgment was not trammeled by hereditary rank or restrictions on thought. Instead, “the recognition of the freedom and dignity of man” was the distinctive and “vital principle in our literature.” [7]

To nurture the American mind, Griswold urged the creation of a national university, “into which only learned men can enter, where there can be a more thorough literary and scientific culture,” to train an intellectual elite who would spread learning through the rest of the nation. There should also be libraries, art galleries, and other cultural institutions, but all must be built on a liberal bourgeois basis: “Our wise and liberal merchants, manufacturers, farmers, and professional men—we have no drones,—are beginning to understand that the true doctrine of Progress is comprised in the world Culture.” Without any other state aid, “literature, the condensed and clearly expressed thought of the country, will keep pace with its civilization.” [8]

***

Viewed from a certain vantage point, this is claptrap. But it’s familiar claptrap, not so very different from any other effort to map an ideal “American mind” or liberal tradition. The chief feature distinguishing Griswold’s idea of American intellectual history from concepts promulgated a century later, I think, is how organic it was. Griswold wanted an elite class of intellectuals, but he seemed to view them merely as servants of a culture that already existed, in incomplete form, as a result of American social conditions. It was an intellectual culture embodied in every poem, every story, every play or piece of music, and every theological treatise that faithfully represented the United States and its people. All of these forms of cultural expression were part of America’s intellectual development.

The paradox is that the national university Griswold wanted—an elite school built on professional, bourgeois, and progressive assumptions about intellectual discipline—would come to exist, after a fashion, in the university system of the late nineteenth century. And it would, by some accounts, be partly responsible for killing (easy belief in) the organic unity of American intellectual life. Indeed, that research university system seems to be largely responsible for the assumptions governing debates over the boundaries of intellectual, cultural, and social history today.

_______________

1. Rufus Wilmot Griswold, The Prose Writers of America: With a Survey of the History, Condition, and Prospects of American Literature (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1847).

2. Samuel Johnson, “Preface,” A Dictionary of the English Language, vol. I (London: J. and P. Knapton, T. and T. Longman, C. Hitch and L. Hawes, A. Millar, and R. and J. Dodsley, 1755), [vii].

3. Elihu Palmer, Principles of Nature: Or, a Developement of the Moral Causes of Happiness and Misery among the Human Species, 3rd ed. ([New York], 1806), 137; “Review of Books: The Advancement of Society in Knowledge and Religion,” Congregational Magazine, 7.8 (July 1825), 359; “Reviews: An Address on Female Education,” American Journal of Education, 1.3 (January 1828), 52; “Art. V.: The Philosophy of the Active and Moral Powers of Man,” American Quarterly Review, 6.12 (December 1829), 361.

4. “Analyses critiques: Discours sur le progrès et l’état actuel de l’hydrographie en Espagne,” Nouvelles Annales des voyages, de la geographie et de l’histoire, vol. 29 (1826), 81 ; Honoré de Balzac, Histoire intellectuelle de Louis Lambert (Bruxelles : Société Belge de Librairie/Hauman, Cattoir et Co., 1837); “Littérature : Histoire de la littérature romaine,” Nouvelle Revue germanique, vol. 14 (May 1833), 35-36.

5. [Samuel Astley Dunham], The Cabinet Encyclopædia, ed. Dionysius Lardner, vol. IV: History: Europe During the Middle Ages (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longman, and John Taylor, 1834).

6. Griswold, Prose Writers, 13. The phrase “Anglo-Saxon” was not necessarily intended to connote racial exclusion—at least, that was probably not the reason Griswold chose it. In context, instead, the phrase stressed white Americans’ national kinship with the people of Britain. The creation of the United States, in other words, opened a new chapter in English intellectual history.

7. Ibid., 47-48.

8. Ibid., 49.

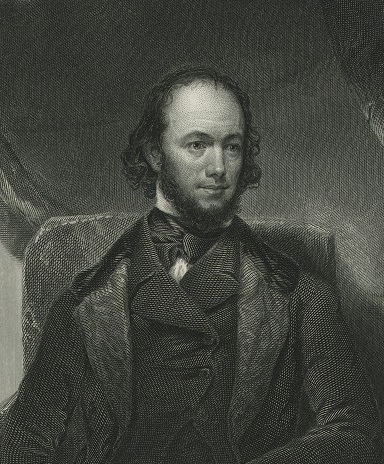

Image: Rufus W. Griswold, New York Public Library, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, image digital ID 1249134.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

“What’s the difference between intellectual history and social or cultural history? It’s a question about subject matter and methodology. More subtly, it’s also a question about political perspectives, models of causation, and the historian’s degree of elite-white-male-ness. More subtly still, it’s a question about academic hiring standards.”

I’ll grant the point about political perspectives, since a fair share of the cultural history I’ve run across, at least in my field, has been about using it to advance political agendas for which intellectual history was a poorly suited vehicle. But “the historian’s degree of elite-white-male-ness”? Really? If you’d said the subject’s degree thereof, that’s a hard statement to refute, at least for much of the history of intellectual history as a field.

But if construed as written you’re saying that the scale of cultural-to-intellectual history can be plotted along the line of one’s elite-white-male-ness, whatever that is. Or it tracks with something, since it’s not articulated just what the relationship of the two variables is. But then if you removed the eyebrow-raising stuff, you’re left with methodology and subject matter, which isn’t really exceptionable.

“Viewed from a certain vantage point, this is claptrap.”

Is that the vantage point of intellectual history or cultural history? A loaded question, at least on its face. But I think one of the justifications of cultural history has been to re-examine things that intellectual history dismissed, if not as claptrap, as not worth its attention. That said, I do think the statement begs the question (strictu sensu).

On your first point, I don’t agree with the viewpoint I’m flippantly describing. On the contrary, I think it’s quite wrong to identify intellectual history as an exercise for or about elite white men. I’m just suggesting, with tongue partly in cheek, that some people do still take for granted that intellectual history is mostly such a project, whereas social or cultural history isn’t (or isn’t to the same degree, or isn’t in its essential features and tendencies).

As for the second point, I think the vantage point I have in mind is simply cynical hindsight. Griswold makes predictions about American culture at large, both high and low (as we might anachronistically say), and about higher education of all kinds, and I’m not sure his dream has come to pass.

On the other hand, I’m also not sure he was wrong about the animating ideals that would be evident in the work of American intellectuals, literati, artists, scientists, or whatever you want to call them. For me, the question is not whether he’s describing American intellectual life versus cultural life; the question is whether he’s attempting to describe a quotidian reality, an achievement, or rather a sort of platonic idea that American culture always approaches but never reaches.