In 1931, Theodore Dreiser slapped Sinclair Lewis in the face. Probably twice, maybe three times.

In 1925, Harold Stearns, one of the most famous expatriates of the 1920s, threatened to sail back to the United States just so that he could “punch [Lewis’s] face in.”

In 1950, Ernest Hemingway published Across the River and Into the Trees, which contained a portrait of an unnamed but clearly identifiable Sinclair Lewis, who was described in this manner: “[he had] a strange face like an over-enlarged, disappointed weasel or ferret. It looked as pock-marked and blemished as the mountains of the moon seen through a cheap telescope and . . . it looked like Goebbels’ face, if Herr Goebbels had ever been in a plane that burned, and not been able to bail out before the fire reached him… A little spit ran out of the corner of his mouth as he spoke.”

In 1940, in the posthumous You Can’t Go Home Again, Thomas Wolfe created a see-through stand-in for Lewis named Lloyd McHarg. This is how he depicted him:

There were three men in the room, but so astonishing was the sight of McHarg that at first George [the Wolfe character] did not notice the other two. McHarg was standing in the middle of the floor with a glass in one hand and a bottle of Scotch whiskey in the other, preparing to pour himself a drink. When he saw George he looked up quickly, put the bottle down, and advanced with his hand in greeting. There was something terrifying in his appearance. George recognized him instantly. He had seen McHarg’s pictures many times, but he now realized how beautifully unrevealing are the uses of photography. He was fantastically ugly, and to this ugliness was added a devastation of which George had never seen the equal…

His face did not have that fleshy and high-colored floridity that is often seen in men who have drunk too long and too earnestly. It was not like that at all. McHarg was thin to the point of emaciation. He was tall, six feet two or three, and his excessive thinness and angularity made him seem even taller. George thought he looked ill and wasted. His face, which was naturally a wry, puckish sort of face—as one got to know it better, a pugnacious but very attractive kind of face, full of truculence, but also with an impish humor and a homely, Yankee, freckled kind of modesty that were wonderfully engaging—this face now looked as puckered up as if it were permanently about to swallow a half-green persimmon, and it also seemed to be all dried out and blistered by the fiery flames that burned in it.

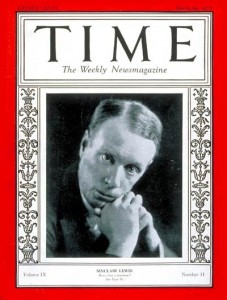

The condition of Sinclair Lewis’s adult face was the result of an excruciating case of teenage acne; even after it had dissipated, the scarring was severe, and Lewis probably exacerbated it with what were some very questionable treatments, including one that apparently injected small amounts of radium into his skin.

Yet he was, by and large, able to conceal the worst of the signs of these traumas through skillful photographic manipulations: some primitive forms of airbrushing, clever poses, and artful uses of light and shade. But these techniques were only successful in presenting a face to the public; in private, of course, there was nowhere to hide.

Dreiser’s slaps and Stearns’s threats were not necessarily a response to this division between the public and the private face, but Hemingway’s and Wolfe’s novelistic portrayals clearly were. But even with Dreiser and Stearns, the public/private line played a major factor. Dreiser slapped Lewis at a private-ish dinner honoring the Russian writer Boris Pilnyak; Lewis had stood up to toast Pilnyak, but told the assembled luminaries that he in good conscience could not with a plagiarist in the audience. Most in attendance may not have understood quite what he was saying, though quite a few likely did: accusations had been circulating for a few months to the effect that Dreiser’s new book on the Soviet Union (titled, modestly, Dreiser Looks at Russia) lifted a significant chunk of text from the correspondent Dorothy Thompson’s book, The New Russia. Lewis was, at the time, Mr. Dorothy Thompson. Dreiser confronted Lewis in an alcove or cloakroom and dared him to repeat his charges. Bystanders separated the two men, but not before Lewis had done so and Dreiser had delivered a couple of blows. It should also be noted that only a handful of weeks before, Lewis had been in Stockholm, receiving a Nobel Prize that Dreiser badly wanted and thought he deserved.

Stearns’s complaint was a little better-documented; Lewis had visited Paris and tried to hobnob with the US expatriate community there, but was routinely rebuffed. By most accounts hurt by the scorn he encountered, Lewis wrote an essay for The American Mercury which mocked the Lost Generation—and everyone else: Upton Sinclair, writers for the slick magazines, himself. But Stearns took offense, recognizing himself in an anonymous portrait of a notorious sponger, whose hot air about the book he was going to write was wearing thin even among the avant-gardistes. He gave an ill-tempered interview to the Paris edition of the Chicago Tribune threatening and protesting Lewis; Lewis responded that he didn’t know why Stearns would have identified himself with such a character.

One way to read this brief history is simply as an example of the transition from character to personality: the frustration that other writers exhibited with the artificiality of celebrity, exemplified by their aggression toward the managed persona—literally, mask—of Lewis as contrasted with the private, uncontrolled face they actually saw, the shreds of character behind the airbrushing of personality.

Yet it is considerably more complicated than this. If Lewis’s public image was managed through the machinery of celebrity, his opportunities to interact with Wolfe, Hemingway, Stearns, and Dreiser were equally created and mediated by that same machinery: the face he could not hide from his rivals—and which they felt compelled, by jealousy or spite, to draw the world’s attention to—was still, to them, a famous face, even if their access to it was conditional on their also being famous.

Moreover, the separation between Lewis’s “mask”—his public image—and his “face”—the unairbrushed visage his fellow literary celebrities had access to—was itself a creation of the press. Reporters were interested in maintaining certain lines of access—reporting on gossip like the Dreiser slap, but also more mundane details like the title of Lewis’s next novel—but not others. Unlike today’s tabloids, where a flabby bikini photo or a makeup-less trip to the gym makes the cover or the homepage, celebrity gossip from the first half of the twentieth century (and perhaps I am wrong here—please correct me, if so!) seems to have been uninterested in exposing celebrities’ corporeal deceptions, their attempts to keep up appearances. But that was not because such deceptions weren’t going on: the newshounds just didn’t track that form of prey. I have found what Lewis’s friends and rivals might have recognized as euphemisms for Lewis’s facial condition in the profiles written about him, but nothing so stark or so obviously cruel as Hemingway or Wolfe.

I am truthfully at a loss to figure out precisely why: I have some ideas, but nothing that has entirely crystallized. What does this lack of interest in exposing the unvarnished truth about celebrities’ physical appearances tell us about cultural norms of this period? And was, as I have suggested, Hemingway et al.’s desire to strike, strike through the mask a sort of chafing against these norms, a form of impatience with the decorum of celebrity as it continued to readjust to new journalistic practices and technological possibilities?

I will close with one final thought. With the uploading of British Pathe’s archive of newsreel clips, I immediately looked up Sinclair Lewis. There was one clip, from 1938, featuring Lewis working with a troupe of summerstock players to mount a play from his 1935 novel, It Can’t Happen Here. What stands out to me now is Lewis’s voice: I had not heard it before, and listened intently for the mix of Midwestern twang and Yankee sharpness that descriptions I had read referred to. For us today, I think, what is often most shocking about encountering the past through audio or video recordings is just how unprepared we always are to listen to them: it is so terrifically difficult to describe a voice in a manner that will summon its tone and timbre with fidelity before we’ve heard it. Faces hold few surprises for us, I think, but the voice—the voice still jolts.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andy, what a fine and fascinating read.

Yes, the voice still jolts. Perhaps this has to do with the way that hearing is also at some level “tactile” in a way that vision is not. The voice raps on our tympanum, it has a vibe, it physically shakes us, a sensory experience that is to varying degrees accessible to the hearing impaired. Voices are embodied things.

On the tabloid tendency to elide the mechanics of celebrity “face-saving” — was that true to the same degree in tabloid writing about women’s appearance?

This is a great piece. A few stray thoughts. I think you are correct that the interest in flaws in celebrity appearance is a newer phenomenon, owing to a few factors. One that comes to mind relates to a passage from Richard Hoggart, who passed away recently. In The Used of Literacy, he talks about working class women who would joke with their friends “I’ve got my ‘hypocrite’ on” when they wore supportive garments… In other words, there was more of a public acknowledgement, at least in British working class culture, of the gulf between “natural” appearance and the ways we try to hide imperfections. That would organize a different moral economy of appearance vs. reality than is currently regnant.

Also–because I think this is a really interesting line of inquiry, and because I can’t resist–I should say that there is a great theoretical literature on faces. Deleuze and Guattari’s chapters on “faciality” are very rewarding, and there is interesting work on post- and inter-faciality in our current age of facebooks, selfies, etc. I’m sure you know this stuff… I guess this is more my broken record wager that a little French theory might make the analysis really take off…

J.P. Morgan had a disfigured nose. Being that he was insanely wealthy and powerful, and that photography was less ubiquitous than it is today, he was able to control nearly all the pictures of him that existed. There are very few photos that show what he really looked like.

Sorry, everyone, for my extreme tardiness in returning to this post. A few stray thoughts:

LD: Clearly, the normative body-image of women has changed enormously over this period, so it’s difficult to say precisely what was tactfully ignored and what was not even regarded as a cosmetic faux pas. I would love Anne Helen Petersen’s input on this, but it seems as if the punitive aspect of today’s tabloids was muted for both sexes, and for a very practical reason: copy sold because the celebrities weren’t “like us,” whether their difference was based in physical beauty or (as with Lewis), creative energy; copy did not sell because they had the same skin problems or weight issues we do. But like I said above, this is a slightly informed stab in the dark, not a thoroughly-sourced claim.

Kurt: I wanted to delve a little into some theoretical connections here, but I was writing away from my desk/books, and, well, I went on long enough anyway! But yes, I completely agree, there is so much fascinating work that has been done on the face, from Goffman to Levinas to Godard (have you seen Notre Musique? A remarkable meditation on these themes.)

Mike: An excellent parallel. And we even see in some literary portraits–like John Dos Passos’s in USA, if I’m remembering correctly–an emphasis on his physical “grotesqueness,” perhaps for very similar reasons–it’s a way to express one’s frustration over the power Morgan had to control access to his physical presence (and thus to screen those who could see his “real” face).