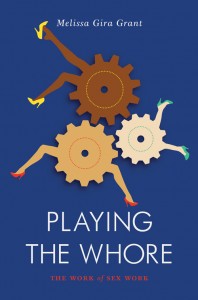

Reading Melissa Gira Grant’s superb new book Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work, I am reminded of a scene on the formulaic but occasionally brilliant sitcom Modern Family.

The old-fashioned paterfamilias Jay Pritchett takes his urbane young stepson Manny on the latter’s errand of selling wrapping paper door-to-door to raise money for charity. The setting being Southern California, they encounter a variety of site-specific screwballs. As they approach one door, a long-haired man cuts them off, mid-pitch: “I’m sorry, I don’t believe in wrapping paper.” Jay explodes: “What do you mean you don’t believe in wrapping paper? It’s not Bigfoot. It exists!”

The joke pivots, of course, on the double meaning of “I don’t believe in.” At the most straightforward level, the joke is on Jay: the stick-in-the-mud old-timer who hasn’t quite internalized the new ethos of activist consumer citizenship, wherein to say, for example, “I don’t believe in bottled water” is also to make the claim that bottled water should not exist, to subscribe to the belief that refusal of the offer of bottled water (however rude or hostile) contributes meaningfully to the abolition of bottled water.

At the most passive aggressive, or just plain aggressive level, “I don’t believe in” is a kind of violent blotting out by means of psychic foreclosure: “this thing should not exist so it cannot exist.” Structurally, as Klaus Theweleit wrote about the post-WWI paramilitary officers who would evolve into the SS and Tim Dean insisted vis-à-vis the Reagan-Bush-Clinton reaction to the crisis of AIDS, this is something like a generalized “social psychosis,” a condition that warrants and authorizes a tremendous amount of real violence against the things and people one does not believe in in order to make them go away.

It is thus worrying that equivalents of the re-doubled “I don’t believe in wrapping paper” permeate the current moment. It is at the heart of neoliberal projects like charter schools (“I don’t believe in failure”). It creates moralized zero-sum debates about everything from breast-feeding (“I don’t believe in bottles”) to atheism (“I don’t believe in believing”).

Meanwhile, Jay Pritchett’s analysis remains cogent: “It’s not Bigfoot. It exists.” In the case of the Modern Family episode, we have the spectacle of a well-to-do “green” yuppie refusing to buy wrapping paper from a child for charity—missing the point of the exercise, which is to help some kid raise money for a school trip or what have you––in order to register an ostensibly moral claim which is nonetheless illegible in the form it is articulated. Will this act of refusal lead to the obsolescence of wrapping paper? What is anyone supposed to do with “I don’t believe in wrapping paper”? What kind of ethics, whether couched in Kantian imperatives or more radical premises, can be derived from “I don’t believe in wrapping paper?”

Thus, as is often the case with Modern Family, a show that is often deeply conservative despite its surface progressivism, it is the out-of-touch patriarch who is made the voice of reason. Nevertheless, I think that Jay Pritchett here articulates an ethics worth taking seriously. Put another way: if the Jay Pritchetts of the governing and chattering classes would abandon their commitments to the “I don’t believe in” and embrace “It’s not Bigfoot. It exists” as a credo, the world might overnight become a kinder, more sensible, and fairer place.

This long preamble about Bigfoot prepares us, I hope, to appreciate the extraordinary accomplishment that is Playing the Whore. In part, I have opened this essay in this way in deference to Gira Grant’s procedures. Playing the Whore negotiates beautifully the contradiction or paradox that feminist scholars of pornography have long noted: studies of titillation often take on the structure of alternating concealment and disclosure that is the essence of the erotic. This is true, as Susan Stewart once observed in a virtuosic close reading of the Meese Commission Report on pornography and the Marquis De Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom, even when, especially when, the interpretive intention is to register disgust and outrage.

In any event, what Playing the Whore cannot do, if it is to succeed as it does in the work it sets out for itself, is to flirt with the oscillation or dilation that charges language as “sexy.” To map out and analyze the political terrain of sex work, in other words, requires a bracketing of sex, or at very least of sex-qua-representation. This is a book about labor history, labor politics, and the possibilities of a new labor imaginary (or a new set of affiliations rooted in the labor movement’s core ethical principle, to which actually existing trade unions have been only inconstantly faithful, of “solidarity”). No one covering the recent unionization attempt at the VW plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee thought it necessary to insist that the drive could not be properly analyzed without thinking long and hard about what it is to install a windshield. When the topic is sex work, contrarily, people start demanding details; we send our inner Staughton Lynds home and call up our inner Adrian Lynes. This is a problem. To say the least.

Playing The Whore proceeds, like Jay Pritchett with a pragmatist relationship with reality. Sex work, like wrapping paper, and unlike Bigfoot, exists. Feminist legal scholars like Margaret Radin (a figure I have chosen carefully, because she is a pragmatist feminist Hegelian with strong commitments to Western Marxism and, in particular, a Lukácsian critique of reification, and not a single-issue demagogue or right wing moralist: in other words, she is a scholar with whom many readers would be inclined to agree) have long proposed sharp legal limits on sex work for two ostensibly pragmatist reason: 1) sex as work makes sex into a commodity, which is not how we ordinarily treat sex in our society, and thus poses a threat to human flourishing; and 2) sex workers often choose sex work as a “desperate choice,” and thus cannot be analyzed as rational market actors.

Gira Grant is part of a growing initiative, on the part of heterodox scholars like Laura Agustín, Constance Penley, and Heather Berg, who seek to reject every part of this rubric. It is simply not true, they demonstrate, that people today do not treat sex as a commodity, and it is almost impossible to find any historical example of a commercial society in which sex has not been sold (or without artistic and literary examples of sex and sexuality as at least partially commodified).

For those who believe that sex workers are uniquely forced to make “desperate choices,” they might recommend an hour or two in any proletarian workplace in any corner of the capitalist world. There are very few “choices” in capitalism that are not “desperate.” This is, one might argue, the single point that Karl Marx tries to establish, in a thousand different ways, in Capital.

Under “desperate” circumstances, which is to say “ordinary capitalist circumstances” sex work is often the best option, in several respects. It usually pays better than starvation-wage factory work, and frequently gives the worker more autonomy and free time. (There are also sex workers who see their work in aesthetic or therapeutic terms and who would reject completely the idea that their work required any further justification).

In moral terms, is anyone certain that sex work is categorically worse than working an assembly line in a taser factory, playing bass in the band at Henry Kissinger’s birthday party, or lobbying Congress to impose sanctions that will guarantee a certain number of deaths in a given period of time? Is anyone certain that sex work is not in fact superior, in ethical terms, to such employments? If there is something about all of this that bothers us, it is the structure and character of contemporary capitalism. This is what Playing the Whore reminds us, again and again.

Thus Gira Grant asks of the United States, one of the last industrialized nations which continues to outlaw sex for sale: “Why do we insist that there is a public good in staging sex transactions to make arrests? Is the point to produce order, to protect, or to punish?” By working through a variety of historical genealogies, sharing insights from forays in investigative reporting, and meditating philosophically upon the place of sex work in the American imaginary, Gira Grant produces a strong argument that the point of the law of sex work is almost entirely divorced from authentic concern with the wellbeing of those who sell sex as part or all of the work they do to survive. At every turn, Gira Grant wishes to unsettle the conventional gaze, to shift from concern over the harm sex workers do to society to the harm that society does to sex workers.

Such a perspectival turn is needed, Gira Grant argues, because “carceral feminism,” a new political philosophy ostensibly born out of the women’s movement, committed to solving all problems with the single hammer of policing and jails, has joined the traditional anti-sex work alliance of social conservatives, urban growth machine gentrifiers, and moral hygienists. Under such circumstances, and with reliably regular inspiration from neo-Victorian “white knight” pornographers like Nicholas Kristof, the space for a bottom-up, sex workers’ rights activism seems to have narrowed; the set of potential allies reduced. In place of a politics led by sex workers themselves, progressives often gravitate to the fantasy of a pro-woman “Swedish model” of “attacking demand” (a fantasy that often has the effect, Grant notes, of punishing dozens of women for every highly publicized male “john”).

While reliable social-scientific research on sex workers is scarce (most researchers are hamstrung by normative commitments, projects are often funded by ideologically questionable foundations, and sex workers are wisely wary of talking to sociologists), the best studies, detailed in Playing the Whore, present a stark reality. The universal prescription of “more policing” has the predictable effect of more violence against women—by the police. Negative encounters with cops are far more common than negative encounters with clients. Chandan Reddy has written recently about the increasingly dominant neoliberal paradigm of “freedom with violence”—of human rights for some as guaranteed or amended by the destruction of the bodies of others––and Playing the Whore might be seen, in one way, as an amicus brief for Reddy’s project. “Opponents of sex work decry prostitution as a violent institution,” Gira Grant writes, “yet concede that violence is also useful to keep people from it.” The desire to ensure that others are not degraded––is that, really, the desire?––has come to degrade its most fervent adepts.

Writing as part of a joint-venture of the venerable Left publishing house Verso and the excellent New York-based socialist journal Jacobin (other titles in the first run include Michah Uetricht’s book on the Chicago teachers’ strike and Benjamin Kunkel on utopia), Gira Grant pursues, as one would expect, a historical materialist understanding of the political economy of sex work and a bottom-up history of sex worker activism.

But there are other sources of analytical inspiration here, too, which make Playing the Whore such a fascinating and rewarding read: the anti-carceral anarchism of groups like Critical Resistance and Copwatch; the insistence, on the part of women-of-color feminists that politics proceed from a non-Manichaean ethics and sensitivity to what Avery Gordon calls “complex personhood.” By recovering moments of solidarity between radical homemakers, sex workers, and “others,” Gira Grant’s text also reflects the resurgence of interest in the “Wages for Housework” movement of the 1970s, about which many of us began to think anew after reading Kathi Weeks’s recent The Problem With Work.

In the US historiography context, Playing The Whore might be seen as part of a broader initiative to properly appreciate the radicalism and effectiveness of political actors in the 1960s and 1970s whose hostility to respectability politics led to their marginalization in historical metanarratives: I am thinking of the work of Premilla Nadasen, for example, on “welfare rights’ activists and Annelise Orleck on the African American War on Poverty front-line workers in Las Vegas.

There is so much more to say about the vital and challenging work performed by Playing the Whore

. Like all discourse-changing interventions, no distillation of its arguments properly does it justice. Gira Grant is an extremely skillful stylist, and the reader marvels at the economy and leanness of the prose.

To conclude, in deference to the place and time in which this essay appears, it might be useful to suggest a contextual frame for thinking about Playing the Whore that extends beyond sex work debates. One such frame might be the continuing rise, within feminist theory and research, of a strong anti-foundationalism, since the 1980s (but much more noticeably since the turn of the millennium).

What differentiates this feminist anti-foundationalism from garden variety male postmodern skepticism, I think, is that the inquiry does not begin as abstract speculation or score-settling, but with concern for women and politics. Thus, while “women” remains in question, always, there is that initial notch carved into the surface of reality that provides orientation—however much we may tarry with sex and gender and social constructedness and genealogy, the institutional context is a feminist studies paper, class, journal, conference, department. While Gira Grant registers strong criticism of mainstream feminism’s bourgeois orientation and its frankly horrific record on sex work matters, I think there is no question that Playing The Whore is a feminist text. In a moment marked by so much disorganization, rancor, and plain ugliness (from “Lean In” to the final battles of the “radfem” caucus against sex workers and the non-cis), Gira Grant’s book is miraculously good news, pointing to potentials for new alliances, epistemologies, solidarities. Whatever the political future may bring, that Playing The Whore is destined, in a matter of moments, to become that rarest of birds, the “instant classic,” is not at all in doubt.

16 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Nothing that Gira Grant says is particularly new, and her factual errors within the book have already been documented elsewhere ( http://feministcurrent.com/8616/toying-with-politics-a-review-of-melissa-gira-grants-playing-the-whore ).

I will use this space to make clear to future readers that the vast majority of socialist feminists (the word “radical” taking on a negative connotation to this clique only with regards to feminism) take great offense to the swift and anti-critical adoption of this woman’s libertarian ideas about sex with minors, sex trafficking, and government support for sex workers. It is a view embraced mainly by males, who Gira Grant attempts to paint as victims of feminist conspiracy.

Unfortunately, simply voicing this perspective via twitter caused the male author of this review to unfollow and block me on Twitter. It seems unlikely there will be much fruitful discussion here.

On this, we no doubt agree.

It’s a little hard to take someone seriously who gets passive aggressive over a twitter block and claims to speak for a majority of women.

Kurt–

“No one covering the recent unionization attempt at the VW plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee thought it necessary to insist that the drive could not be properly analyzed without thinking long and hard about what it is to install a windshield. When the topic is sex work, contrarily, people start demanding details; we send our inner Staughton Lynds home and call up our inner Adrian Lynes. This is a problem. To say the least.”

This seems to me wrong, not in the sense that analysts of the union drive in Tennessee did, in fact, feel the need to focus on what it means to install a windshield, but in the sense that there is a very long tradition on the left that deals with the problem of alienated labor and the qualitative dimensions of modern industrial work. The AFL perhaps won the game of accepting the modern conditions of work and focusing on “bread and butter” issues as the mainstream of modern unionism–but there are a lot of people–beginning at least with Marx, but continuing through people like the Lynds, Daniel Bell, C. Wright Mills, and the new labor historians of the 1970s and 80s, who thought that you could not talk about labor, its organizations, and its goals, without talking about the dehumanization of work, what workers actually _did_ in the hours they spent on the shop floor. Isn’t the concern with the commodification of sex equivalent in some important ways to this line of thinking about alienated labor? I realize that this is probably flipping Grant’s argument on its head (although I’m not entirely sure I understand what her argument actually is) by emphasizing the similarity of sex work and industrial labor in terms of a moral community and a vision of self ownership, rather than her attempt to demoralize sex on the equivalent basis of modern work.

Since the term “libertarian” has been used in the above comment as a way to describe Grant’s position, and I haven’t read the book, do you think that’s an accurate description of her view, and if so, in what sense?

Dan, thanks for this response. A (too) long reply.

You are right, of course, about a certain dissident shop-floor tradition in labor writing, although I have to say that having recently covered the labor-historical tradition fairly thoroughly for comps, this is a minor tendency even in studies of work and collective bargaining.

But I would push back against your claim a little, by pointing out that to get the equivalent scrutiny of the experience and ethical implications of auto work as is demanded in discussions of sex work, one would have to do something like a Heideggerian meditation on tool-being and being-to-handness. Maybe Alvin Gouldner’s early work or some of the writers in Stan Weir’s circle, (we could probably also include Barbara Ehrenreich and Barbara Garson in this list), approach that level of detail and concern.

Even there, it must be admitted that, for example, when I transport what Gouldner has to say about the gypsum factory in Buffalo or Ehrenreich has to say about working for a maid chain to some other example–to thinking about fast food workers or Amazon warehouse staffers or Tennessee autoworkers I am, to a large degree, engaging in some form of mediated fantasy.

We know very little about how other people work, and usually we are upfront about that.

Only sex work presents itself to us as a thing we know completely just by imagining it. (And we know, too, that some people get off on imagining it).

In any event, most authors on contemporary labor matters do not write about the details of the labor process. My point is not that this has never been discussed, but that today it is not part of the conversation. When Steven Greenhouse and Mike Elk and Josh Eidelson, all fine labor journalists, pen pieces on the VW campaign, they speak mainly to the question of organizing the Right-to-Work South, the difficulty of organizing under the aegis of neutrality agreements, etc… and not the work of installing a windshield, and certainly not whether it is ethical to work in a VW factory, given that cars are terrible for the environment, or that assembly line work is dehumanizing, or that VW was started by the Nazis. (These would be mild parallels to the sorts of questions that are asked about sex work all the time).

In fact, we could probably agree that no one could write about such things in any but the fringiest of locations. The question becomes: why is sex work, uniquely among all the kinds of work,, the site of so much fantasizing, so much “knowingness,” and so much moral absolutism?

In many ways, Gira Grant *is* arguing from the “alienated labor”/Braverman tradition of the 1970s that you invoke. Immersion in that literature, I think, leads to a sort of pragmatist realism about the nature of all labor in contemporary capitalism. (Otherwise, one would have to condemn all capitalist labor as impossibly dehumanizing, as some anarchist purists do, and prescribe a universal “refusal of work.” That’s not really an option, though, and thus becomes a species of “beautiful soul” melancholy).

Since all work in capitalism sucks, and involves some amount of coercion, and much of it involves selling affect, emotional labor, and bodily touching of one sort or another, one seeks in vain for the differentia specifica of sex work. I don’t think it can be found, outside of a theological notion of the “sacred,” or a normative and arbitrary separation of “sex” from everything else.

In a secular society, the religious objection holds very little water. In any event, we know from a thousand different sources that sex is not a “sacred” practice that needs to be defended from market pollution; if anything, it is difficult to imagine American sex outside of the market’s libidinal economy. (These are my emphases).

Gira Grant does not want to talk about sex, for all sorts of good reasons. Her point is that today, in contemporary American discourse, a good deal of guilt, fantasy, and anxiety, coupled with bad knowledge and moralizing judgment, leads to policy prescriptions re: sex work that end up being worse for women.

Sex work, like everything else in the world is a complex phenomenon that different people experience differently, on a continuum from work that involves a little sex to work that involves a lot, the result of choices that are more or less constrained. In all matters of regulation and reform, the best option is to listen to what sex workers themselves have to say.

Re: libertarianism. I don’t think Gira Grant is a libertarian in the way intended by those who wield it as a slur. There is no evidence in this book that she harbors any illusions that the market is superior to all other forms of social organization, or that, for example, the New Deal was a “bad thing.”

The “libertarian” tag is a red herring, one that speaks to a certain coarsening of the political imagination on the Left in recent years. For example, macho muckrakers like Paul Carr and Mark Ames relentlessly mock Glenn Greenwald for being a “libertarian” (even though Greenwald delivered the keynote at the major socialist conference last year); Thomas Frank continues to write the same salvo against capitalists in leather jackets.

Sure, of course, I have nothing good to say about Austrian economics or google glasses, either.

But a feminist and anti-racist consciousness (not to mention a Marxist one) makes much of the Left’s turn to a demand for uncritical philo-statism very difficult to swallow. For a time, I toyed with writing an article entitled “The Left and the State: Too Much Frank Capra, Too Little Franz Kafka.”

Seeking to defend the last remnants of the welfare state, we often feel unable to decry the tangible harm done by the state to poor people in the form of policing, surveillance, and incarceration (to say nothing of intransigent labor bureaucracies, the often galling power structures inherent in the university system we are trying desperately to save, the tremendous tensions of the modern medical complex to which we also want everyone to have cheap access). If we must put all these concerns aside or accept our fate as tacit “libertarians,” then I guess I’m a “libertarian,” too.

Gira Grant is very critical of the capitalist “carceral state”–because it hurts the people she cares about, and about whom she wishes for us to care. This is a brave and lonely position, I think, especially these days, even on the Left. It seems to me very distant from what we usually understand by “libertarianism.”

No, I am not a libertarian. Not that it matters, as I don’t think that was meant to say anything in particular about my politics, but to dismiss that I had any. Moving on, then?

Thanks Kurt. I think I’m still puzzled about the book and its argument, but that probably just means that i should read it. Another question, and this really isn’t meant as trolling, so if it reads that way, feel free to say so and/or ignore it: do those who adopt the position Gira Grant and you seem to favor also believe that the category of sexual assault or rape is problematic, and that no special attention should be given to the ways in which sexual assault demands a different response on the part of the legal system than physical assaults or theft do? Given the fact that statutes against rape have a deep history in patriarchal control over women’s bodies, does the legacy of that history require doing away with rape as a special category and how would that end up helping women if that’s the case? And given that prostitutes are often the victims of rape, are we to understand that that crime should be imagined as something like a theft of service or a kind of forced labor rather than a specifically sexual assault?

Great review, Kurt. This is the best sentence I have read all week: “In moral terms, is anyone certain that sex work is categorically worse than working an assembly line in a taser factory, playing bass in the band at Henry Kissinger’s birthday party, or lobbying Congress to impose sanctions that will guarantee a certain number of deaths in a given period of time?”

There are a great many disreputable jobs out there that, once one throws off the golden manacles of bourgeois respectability, come to look a whole lot better. That’s exactly why the bourgeois respectability caucus needs to pour boulders and boiling oil down the side of the keep to prevent such views from gaining a foothold.

This is about real trench combat too, as we can see by the violent reaction of many Blue Devil “ladies” to the Duke porn star revelation. I challenge anyone to defend the claim that whatever she experienced in the San Fernando Valley is worse than the slut-shaming she has endured at the hands the respectibility caucus: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/03/20/duke-porn-star-belle-knox_n_4995159.html – a more perfect example of Grant’s argument would be hard to imagine.

Thanks so much Nils. Yes, the Duke case is a perfect example, and I have argued recently with some very brilliant liberation theology types about it. They seem quite tied to an Augustinian frame for thinking about sex and sex work… but the irony is, of course, that the young woman is getting so much more flack than if, say, I don’t know, Richard Perle decided, a la Rodney Dangerfield in Back to School, to enroll at Duke as a freshman…

I will have to add this book to my reading list, specially because I am a firm believer in the unionization of sex workers and the protection of their rights as workers. I am not fully convinced however about the question of “desperate choice”–it is clear, at least to me, that people’s choices in all respects–from education to work to leisure–are constrained by gender, race, class, culture-based inequalities. And there are many instances where sex work actually is forced and essentially a form of slavery, involving underaged people in intensely high risk situations. but this is an agency that nevertheless operates in very uneven relations of power. In the end, I personally hope that sex work, at least as it exists in most countries, disappears. In human history there is never an impossibility in terms of transforming relations of power.

By the way, regarding your allusion to the use of libertarianism as a slur in connection to Glenn Greenwald, I haven’t read the writers you mention, but doesn’t Greenwald identify quite explicitly as a “civil lbertarian”? Let’s remember Greenwald was very vocal in supporting the SCOTUS Citizens United decision. Speaking at the socialism conference a socialist doesn’t make you, progressive and even anarchist peeps are often invited.

Part of the sentence before “but this is an agency that nevertheless operates in very uneven relations of power.” was cut out.

I meant to say: I am all for recognizing the agency of sex workers,”

Peace out.

Khalil, as always, thanks so much for this comment. And yes, I think GG identifies as a “civil libertarian.” If I have my history correct, he evolved to a left-libertarian of some sort from a youth as a right-libertarian of a more or less Cato Institute sort. This is often treated as akin to the Paul de Man revelations… as I read it, this is now a stock move to discredit a foe in intra-left disputes.

So, when I am glad, for example, that Rand Paul, an otherwise horrific figure, protests NSA abuses, my conversation mates feel they have all the ammunition they need to “win” the argument and dismiss me from the set of serious people of the Left. This is a big problem, I think.

Agreed, specially on the politics of mud-slinging in the left. I actually enjoy Greenwald’s work (except on the Supreme Court decision and similar matters where he puts free speech above everything else).

Libertarianism deserves more attention from the perspective of intellectual history, it is more complicated than some make it seem. Left libertarianism is particularly interesting as a phenomenon, its links to anarchism in particular. Then there are the so-called anarchist capitalists (I am still trying to figure them out), it can be quite confusing to map an ever shifting political spectrum, particularly outside mainstream politics (and, just as a disclaimer, I will say I don’t identify as a libertarian of any stripe, color, or flavor).

Dan Wickberg,

If the questions in the latter half of your comment are sincere, I can catch you up off-line about why the sex work/rape elision you have engaged in here is extremely problematic. It strikes me as unambiguously aggressive. I don’t like that.

I tried to be careful to present Gira Grant as a thinker at the intersection of multiple intellectual and political traditions. There is no single “line.”

Because it matters, and I have clearly failed to distill the book’s central point: much of the contemporary discourse on sex work, from right to left, is premised on bad knowledge. Things marketed as helping women can be shown, empirically, to hurt them. Thus, as I understand it, crackdowns on sex workers’ online communities have made it harder for sex workers to share info on dangerous clients. Police use condoms as evidence to arrest women on the street, so people stop carrying them. And across the world, it is lieutenants of law and order who perpetrate the vast majority of assaults on sex workers.

Kurt–My apologies. As I said in the comment, I was concerned that my question would come off the wrong way, but it was in fact sincere and not intended as aggressive. I’m trying to work out how certain kinds of distinction that on a gut level I think are important (e.g. that rape is _not_ just a variant of assault) can be preserved under the logic of ridding us of the notion that sex work is somehow different in kind from other work. I read your take on Gira Grant as saying that she represented a logic of demystification, of stripping sex of its special or “sacred” significance in order to provide a means of legal redress for sex workers. That raises questions about the consequences of the logic used. My question was not designed to elide an important distinction, but to ask what the implication for domains that we (or at least I) might wish to preserve are. I’m really not trying to start an argument or be aggressive.

Okay, cool, I’m glad we are on the same page with this.

Sexual assault, and sexual harassment are crimes so rooted in fundamentals of tort and criminal law, stretching back to time out of mind, that the sanctity of “sex” as a thing we would wish to remove from the market seems to me a separate concern. The question is always whether women are seen by the law as possessing sufficient personhood to be injured by assault (sexual or non-sexual) and under what conditions.

The problem, in the first instance, is the law’s misogyny (which has been variable over time, as Medieval historians point out, and which took a sharp turn for the worse at the dawn of the Victorian Era), not the phenomenology of sex.

In other words: there are strict rules on how adults, male and female, are allowed to touch one another, based on the notion that the law protects us against unwanted contact or speech that bothers us. Sex’s specialness does not seem necessary here.

Historically, it seems to me that marriage, far more than sex work, has been the arena for the sort of problem you bring up here. We might think of Amy Dru Stanley on links between anti-slavery campaigns and the drive to register marital rape as a crime within American jurisprudence. But Ross Douthat, penning his hundredth hymn to marriage, is never asked about rape. Every writer on sex work is asked this, all the time.

A common premise, shared by many anti-sex work writers and many writers on labor (this includes people who self-define as Marxists) is that the sex work client purchases complete control of the sex worker, just as the capitalist employer purchases complete control of the industrial worker…

Such a view negates completely the reality of organizing among all workers in all times and places. To put a fine point on it: it is a view completely at odds with the evidence laid out by labor historiography.

Workers develop all sorts of ingenious methods of self-protection to regularize, routinize, and limit their exploitation, up to and including state-backed collective bargaining. The political horizon suggested by Gira Grant’s book, then, far from being libertarian, looks towards sex workers’ unions (as have been established at many different times and places, including in the US) and the kinds of ordinary protections to which the de-sacralization of sex (in my view, a process that is already accomplished, so a political/discursive acknowledgment of sex’s de-sacralization) might lead.