Recent weeks have included several posts by both myself and Lora Burnett on sports and recent American history. I’d like to continue that trend, but with a slight twist. The intersection of race and sports, not to mention gender and sports, has been written about extensively by both journalists and academic historians. A more recent trend in sport historiography, however, has been to think about what pushes people to root for certain teams. Several books on 1970s National Football League clubs shed some light on how people chose to root for certain squads.

Sport history in the US is replete with people choosing to root for teams based on geography. This is, for all intents and purposes, the default position of how fan bases grow and develop. However, other elements can provide a rationale for supporting certain teams. Think, for instance, of the Brooklyn Dodgers and their African American fan base after the team signed Jackie Robinson. Black support for the team was a cultural and political act in the 1940s, signaling not only their hopes for Robinson (and, eventually, other Black players as well) to do well, but their demands for a chance to be on a level playing field in politics, economics, and American life in general.

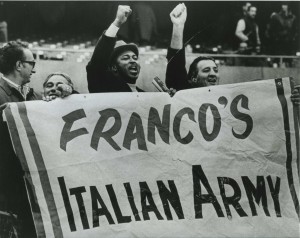

Politics has played an important role in determining sports loyalty for many different groups of people. The rivalry in Spain between Barcelona and Real Madrid, stoked during and after the Spanish Civil War by the actions of the Fascist ruler Francisco Franco, provide an example of how sport can be used as a mode of resistance to government authority. Teams also provide some form of regional or, in the case of the Olympics and World Cups, national identity. Brazil’s national team in soccer has given the nation a sense of national pride since the 1930s. The ESPN documentary Once Brothers made it clear that, in many ways, the final resting place for Yugoslav identity was their skilled and talented basketball national team of the late 1980s.

The 1970s-era NFL also provided a place for people to come together around shared identities that were wrapped up in race, gender, and class. This is the argument put forward, at least, by Chad Millman and Shawn Coyne in their book Those Who Hit Hardest: The Steelers, the Cowboys, the ‘70s, and the Fight For America’s Soul. Two of the most iconic teams of the decade (I’ll get to the third one in a moment) are viewed through a lens that’s familiar to any of us who’ve read Jefferson Cowie. In short, the Steelers came to represent not just Pittsburgh, but American labor in general. The Cowboys, meanwhile, were the stand-ins for America’s Sunbelt region. It is an interesting premise, one that’s fleshed out throughout the book by comparing and contrasting the two teams before and during the 1970s.

The 1970s also belonged to a third NFL team: the Oakland Raiders (with all apologies to the Miami Dolphins). Badasses: The Legend of Snake, Foo, Dr. Death, and John Madden’s Oakland Raiders, written by Peter Richmond, gives some sense of the presence of the Raiders on the national landscape. For Richmond, the Raiders were rebel America’s Team: not necessarily for labor, or Sun Belt conservatism, but for everyone else on the outside. The Black Panthers. Hell’s Angels. Those kinds of people.

When we talk about sports teams and fans, it’s important to think about factors such as regional ties, race, and politics. However, it’s too easy to ignore the media angle in all of this. Getting deeper into the intellectual history side of this, sports and media must be analyzed together if we’re to get a better sense of how and why fans chose to support certain teams. How much of a difference does it make if a team is nationally broadcast in the 1970s versus being on the radio in the 1940s? I’m not sure, but perhaps it depends on the sport. The Yankees, from my humble estimation, have been despised since at least the 1920s. But in thinking about the modern standing of teams such as the Cowboys and Steelers, I think at least considering the rise of network television at the same time is important. After all, the 1970s were the era in which football overtook baseball as America’s game, and thinking about what the Steelers, Cowboys, or Raiders meant to fans has to include considering how television played a role in developing people’s tastes and habits during the same era.

I can’t help, in closing, to add that there’s something about the South that’s unique to this situation. Growing up in the 1990s and watching far too many bad Atlanta Falcon teams, I found myself also rooting for the Cowboys. My father did the same thing. And, I suspect, many others did that across the region as well. I don’t think it’s a case of fair-weather fandom, as much as it’s choosing sides when seeing the same team on television all the time. The support for professional teams in the American Southeast is a recent phenomenon when compared to, say, the Northeast or Midwest. The big sports behemoth in the South is college football. In that regard, rooting for Alabama, Georgia, or Tennessee has taken precedence in many households for generations. How the media helped create sports fans, and sports rivalries, is something that the two books mentioned above take a crack at. I think we, as intellectual historians, could also add something to that dialogue.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I love these posts on sports. Please keep them coming. Other than the obvious reasons for a sports fan to enjoy them, they have the virtue of making clear and undeniable the lack of distinction between the usual “topics of study” in the academy and the supposedly separate “normal life” we all lead.

There are many directions one can go when looking at the question not merely of which teams we choose to root for, but how long lasting and intense fan loyalty is. A fan loyalty index was actually created for baseball back in the 1990s, and various social scientists have identified different “types” of fans and different motivations for fandom, from the motivation of bonding with other fans to feeling a part of and honoring the history of a particular team. It would also seem to me that asking why, for example, Chicago Cubs fans are very loyal (despite everything) but other fan bases not nearly as much could help get at some very interesting dynamics going on in different spaces in the country.

Thanks for the kind words. And the Cubs are a very, very interesting case study to say the least.

And yeah, the distinction between life and the academy is part of the reason I’ve written some of these posts. Moreover, I keep asking myself the basic question, “Why do we care so much about this stuff?”

Robin-Marie – Isn’t this a bit circular ?

I love these posts on sports. Please keep them coming. Other than the obvious reasons for a sports fan to enjoy them, they have the virtue of making clear and undeniable the lack of distinction between the usual “topics of study” in the academy and the supposedly separate “normal life” we all lead.

I suppose my point was that they are valuable even if you do not enjoy sports or have any particular relationship with them.