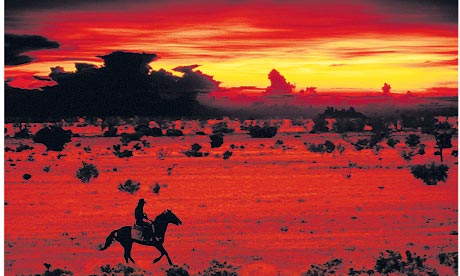

Thanks to Richard King’s kind invitation, I participated in the annual two-day seminar of the UK-based Intellectual History Group (IHG), generously hosted by Michael O’Brien at Cambridge the past few days. The IHG meets at Jesus College in Cambridge every January to discuss a common text. These texts tend to be primary sources broadly of interest to U.S. intellectual historians. Sometimes the focus is theoretical or philosophical. For example, they have agreed to discuss Fredric Jameson at the next meeting. Sometimes the texts are more literary and include novels. We discussed Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West

Thanks to Richard King’s kind invitation, I participated in the annual two-day seminar of the UK-based Intellectual History Group (IHG), generously hosted by Michael O’Brien at Cambridge the past few days. The IHG meets at Jesus College in Cambridge every January to discuss a common text. These texts tend to be primary sources broadly of interest to U.S. intellectual historians. Sometimes the focus is theoretical or philosophical. For example, they have agreed to discuss Fredric Jameson at the next meeting. Sometimes the texts are more literary and include novels. We discussed Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West

this week.

In this post, I will give you a sense of why the IHG chose Blood Meridian as a text worthy of two days of scholarly discourse. But first I would like to make the case that U.S. intellectual historians in the United States should replicate the IHG format. This might be difficult: we would have to travel much greater distances, and we would have to find institutional support like the IHG has found in Cambridge, or pay the costs for such a meeting out of our own pockets. In any case, the IHG is worthy of replication because it puts the Life of the Mind in practice. The discussions were remarkably lively, in part because there was nothing at stake beyond the text and our discussion of it—which is quite enough! And even though the Cambridge setting evokes formal hierarchy, what with High Table and such, the IHG has a distinctly non-hierarchal feel about it. All of the members, from senior scholars to graduate students, participated as equals. In short, the IHG is the ideal of scholarly collaboration.

Blood Meridian generated a wide-ranging scholarly discussion. McCarthy’s fifth novel, Blood Meridian was published in 1985 to very little critical or commercial attention. But after McCarthy’s 1992 All the Pretty Horses won the National Book Award, critics reexamined his earlier works and discovered a masterpiece in Blood Meridian. Harold Bloom describes it as “the authentic American apocalyptic novel,” and argues that it makes McCarthy a “worthy disciple both of Melville and of Faulkner.” Another critic argues that, among the Great American Novels, only Moby-Dick compares to Blood Meridian.

I’m not going to mince words: the experience of reading Blood Meridian was exhilarating. I enjoyed it even more than The Road, which I praised here a few months ago. I could not put it down, and read it very quickly, in the course of two train rides and a flight. As a historian, most of my reading tends to be analytical, skeptical, hermeneutical. Sadly perhaps, reading has become a function of my trade. But I devoured Blood Meridian as my 12-year-old self, as if I could still be mesmerized by the aesthetics of reading.

Blood Meridian

is loosely based on the exploits of the Glanton Gang, a group of American mercenaries contracted by the Mexican government in 1849 to kill Apaches along the dangerous borderlands of Mexico, Texas, California, and what soon became the American Southwest. The Glanton Gang became known as the “scalp hunters” because they traded scalps for bounty. In order to earn more bounty, the gang did not limit its murderous exploits to killing warring Apache tribes. The scalp hunters also slaughtered peaceful tribes and whole villages of Mexicans, trading scalps for profit.

The thing readers will notice first and foremost is the violence of Blood Meridian. It is the most violent book I have ever read, which is perhaps fitting given the story and the setting. But beyond the violence, the most remarkable thing about the book is the sublime prose. Take note of the following, very long, run-on sentence, which describes a group of Comanches on the verge of attacking a rogue group of Americans who have illegally invaded Mexico in the search for spoils shortly after the Mexican-American War:

A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners, coats of slain dragoons, frogged and braided cavalry jackets, one in a stovepipe hat and one with an umbrella and one in which stockings and a bloodstained weddingveil and some on headgear of cranefeathers or rawhide helmets that bore the horns of buffalo and one in a pidgeontailed coat worn backwards and otherwise naked and one in the armor of a spanish conquistador, the breastplate and pauldrons deeply dented with old blows of mace or sabre done in another country by men whose very bones were dust and many with their braids spliced up with the hair of other beats until they trailed upon the ground and their horses’ ears and tails worked with bits of brightly colored cloth and one whose horse’s whole head was painted crimson red and all the horsemen’s faces gaudy and grotesque with daubings like a company of mounted clowns, death hilarious, all howling in a barbarous tongue and riding down upon them like a horde from hell more horrible yet than the brimstone land of christian reckoning, screeching and yammering and clothed in smoke like those vaporous beings in regions beyond right knowing where the eye wanders and the lip jerks and drools.

Oh my god, said the sergeant.

Although consuming such prose was an aesthetic experience that, on first reading, defies analysis, I have in retrospect thought a great deal about the significance of Blood Meridian beyond aesthetics, due largely to the wonderful IHG conversations. In order to render a contradictory, ambivalent, even ironic ethical stance—or what one might call an anti-ethics—Blood Meridian stitches together canonical themes and tropes, from the Bible to Nietzsche. I will take up this analytical discussion of Blood Meridian next week.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

So, Andrew, did you wear a gown or a jacket at “high table”?! 🙂

But, more seriously, thanks for the description of both the book and your reading experience. We all long for books that evoke our earliest memories of reading as fun and escapist, yes? That was your best sales line for *Blood Meridian*—a book I’ve not read (like the two Ben wrote about on Monday) and to which I would not have been attracted if you had led with, and focused on, the violence.

And IHG sounds fabulous. In America we must beg a rich sponsor for such a privilege—a sponsor whose money is hidden behind the network of foundations that pick and choose “worthy” endeavors beyond the realm of normal employment in academia. Who will be our USIH sugar daddy? – TL

I read Blood Meridian sometime in the early ’90s and was very struck by the novel. It indeed has, as I recall, a mesmerizing quality as you put it, even though the prose is not only sublime but is also at times deliberately affected and uses a fair number of rather obscure words, or obscure to me (what, just to take an example from the quoted passage in the post, is a “frogged” cavalry jacket?). (I didn’t read it w/ a good dictionary right at hand but if I ever were to re-read it I might do it that way.)

I’m interested that the novel was the subject of this academic session among intellectual historians. In int’l relations (IR), I’ve noticed occasional references to the book, for ex. in a review-essay (of some books on sovereignty, iirc) that appeared in a IR journal a year or two ago. In particular the figure of the nihilistic Judge Holden, embodiment I suppose of a version of the amoral/immoral ‘superman’, seems to attract attention. But I’m probably anticipating the next post.

Finally I’d like to say that it is very possible to find the book quite riveting even if one has not read much or any Nietzsche and doesn’t catch every one of the “themes and tropes” (to use the post’s phrase).