On Sunday, Richard Sherman made the game-winning play to send the Seattle Seahawks to the Super Bowl. Then, he gave a memorable post-game interview, which quickly became a cultural controversy. Most of the initial reactions to Sherman’s unorthodox interview were negative, some outright racist. Others were more supportive and contemplative. The reception as a whole raises several important questions. What does it mean that so many people were offended by Sherman? What does it say that a harmless bit of bragging by an NFL player generated so much controversy? What does it tell us about the cultural politics of race, about the symbols and codes we use to discuss race? What does it say about the current state of American racism?

In researching the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s, I have come across several such controversies that have helped me make sense of race, meaning, and historical change: Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing; the Sister Souljah moment

; the Water Buffalo incident at the University Pennsylvania. The list of such hullaballoos goes on. One such controversy that I’ve been trying to understand lately is the moral panic over sexually explicit rap music, particularly the music of 2 Live Crew.

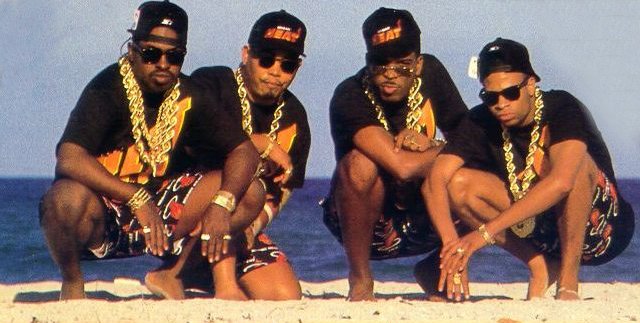

2 Live Crew, a Miami rap band whose 1986 debut album, The 2 Live Crew Is What We Are, took, in the words of one music critic, “sexually explicit rap lyrics to a new level of nastiness.” That album, which included the notorious track, “We Want Some Pussy,” went gold. The band’s next album, As Nasty As They Wanna Be, which featured the wildly popular single, “Me So Horny”, was released in 1989 to even more commercial success. As Nasty As They Wanna Be placed 2 Live Crew at the center of a cultural firestorm—a controversy that carried over from an ongoing moral panic about popular music. Like all good American moral panics, the 1980s music scare became the subject of congressional hearings in 1985 when the Senate heard testimony on the subject of “porn rock.” Such hearings were made possible by the tireless efforts of Tipper Gore and her fellow “Washington wives,” the patronizing title given to the four women who founded the Parents’ Music Resource Center (PMRC). The PMRC successfully convinced record companies to place warning labels on the covers of explicit records and CDs, labels that became mockingly known as “Tipper Stickers.”

2 Live Crew, a Miami rap band whose 1986 debut album, The 2 Live Crew Is What We Are, took, in the words of one music critic, “sexually explicit rap lyrics to a new level of nastiness.” That album, which included the notorious track, “We Want Some Pussy,” went gold. The band’s next album, As Nasty As They Wanna Be, which featured the wildly popular single, “Me So Horny”, was released in 1989 to even more commercial success. As Nasty As They Wanna Be placed 2 Live Crew at the center of a cultural firestorm—a controversy that carried over from an ongoing moral panic about popular music. Like all good American moral panics, the 1980s music scare became the subject of congressional hearings in 1985 when the Senate heard testimony on the subject of “porn rock.” Such hearings were made possible by the tireless efforts of Tipper Gore and her fellow “Washington wives,” the patronizing title given to the four women who founded the Parents’ Music Resource Center (PMRC). The PMRC successfully convinced record companies to place warning labels on the covers of explicit records and CDs, labels that became mockingly known as “Tipper Stickers.”

Conservative groups, including Donald Wildmon’s American Family Association (AFA), also responsible for leveling outrage against Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ and Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, did not think “Tipper Stickers” were adequate warning for the depravities contained within 2 Live Crew albums. Jack Thompson, an AFA lawyer, convinced Florida Governor Bob Martinez that As Nasty As They Wanna Be met the legal classification of obscenity. In 1990, a U.S. District court judge in Florida ruled the album was, indeed, obscene and, thus, illegal to sell. Undercover police then arrested several record storeowners for selling the album, and 2 Live Crew band members were arrested after performing it at a nightclub. No guilty verdicts ever came of any of the arrests, but the legal dispute added to a national controversy that, in turn, took on the added dimension of race.

Most of those who publicly fought to criminalize 2 Live Crew argued that censorship was a necessary step because of the causal nexus between sexually explicit music and the sexual abuse of women and children. The desire to protect children was consistent with the PMRC’s stated rationale for its activism. Gore picked a fight with the music industry after overhearing Prince’s wildly popular song “Darling Nikki,” about a girl masturbating in a hotel lobby, playing on her 11-year-old daughter’s stereo. But moral panic reached new heights with 2 Live Crew. The PMRC wanted “Tipper Stickers” on Prince’s Purple Rain album as a way to inform parents about the content of the music their children were consuming. The PMRC did not intend for the state to censor music in the manner that government officials were going after 2 Live Crew. Why the disproportionate response? 2 Live Crew’s lyrics were indeed more explicit than most. But race almost certainly played a factor.

Phil Donahue dedicated an episode of his daytime talk show in 1990 to the issue of 2 Live Crew and music censorship. Included among his guests were 2 Live Crew rapper Luther Campbell and AFA lawyer Jack Thompson. Thinking aloud about why 2 Live Crew was seemingly being singled out, Donahue stated: “We’ve got to wonder about racism.” Donahue played a Madonna video—from her “Blind Ambition” concert performance of “Like a Virgin,” which included scenes of her stroking herself and gyrating—and asked, “If we arrest Luther how come we’re not arresting Madonna?” One of Donohue’s audience members implicitly answered this question when she stated that 2 Live Crew’s music isn’t “even art, it’s not even music, it’s rap.” Indeed, this was often the argument made by cultural gatekeepers. Noted music critic Robert Bork, for instance, described rap as “generally little more than noise with a beat, the singing is an unmelodic chant, the lyrics often range from the perverse to the mercifully unintelligible. It is difficult to convey just how debased rap is.” Such a take ignored that millions of Americans did indeed perceive rap as music, and as artistic representation worthy of their patronage. As Jello Biafra, the lead singer of the punk band Dead Kennedys and outspoken critic of the PMRC, hilariously responded to the Donahue audience member who denied that rap is music: “Not everyone wants to hear Lee Atwater sing the blues.”

Many American liberals, to the degree that they defended 2 Live Crew against government censors, did so merely out of their stated support for the principles of free expression. Very few argued there was anything culturally redeeming about 2 Live Crew. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who testified on behalf of 2 Live Crew—testimony that perhaps helped the band members get off on all charges—was one of the few exceptions. Writing in The New York Times, Gates argued that 2 Live Crew needed to be understood in historical context. “For centuries,” Gates wrote, “African Americans have been forced to develop coded ways of communicating to protect them from danger. Allegories and double meanings, words redefined to mean their opposites (bad meaning ‘good,’ for instance), even neologisms (bodacious) have enabled blacks to share messages only the initiated understood.” In other words, we were not meant to read 2 Live Crew so literally. Even its most offensive, downright misogynistic lyrics needed to be taken with a grain of historical salt. Gates continued:

2 Live Crew is engaged in heavy handed parody, turning the stereotypes of black and white American culture on their heads. These young artists are acting out, to lively dance music, a parodic exaggeration of the age-old stereotypes of the oversexed black female and male. Their exuberant use of hyperbole (phantasmagoric sexual organs, for example) undermines—for anyone fluent in black cultural codes—a too literal-minded hearing of the lyrics.

Whether 2 Live Crew intentionally wrote lyrics with such a cultural history in mind is not really the point, just as it’s not really the point whether Richard Sherman’s exuberant outburst of bravado was a conscious deployment of parody on the level of Muhammad Ali. 2 Live Crew was popular, in part because, yes, “sex sells,” but also in part because they, consciously or not, tapped into a rich cultural discourse about race and masculinity that was interesting to white and black audiences alike, often for very different reasons. 2 Live Crew, like Richard Sherman, should thus be understood at the level of parody: as exaggerated totems of our racial and sexual anxieties.

This is not to say that we should endorse the content of 2 Live Crew, which was indeed indicative of misogyny, or of Sherman, who is perhaps an emblem of how we consume violence. Rather, we should be aware of our rampant racial hypocrisy. As Gates asked: “Is 2 Live Crew more ‘obscene’ than, say, the comic Andrew Dice Clay? Clearly, this rap group is seen as more threatening than others that are just as sexually explicit. Can this be completely unrelated to the specter of the young black male as a figure of sexual and social disruption, the very stereotypes 2 Live Crew seems determined to undermine?”

That said, go Broncos! (What can I say, I’m from Denver.)

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This post reminded me of my all-time favorite Robert Bork line: “A lot of people comfort themselves with the thought that this is confined to the black community, but that’s not true — some of the worst rappers are white, like Nine Inch Nails.” (source)

Amazing! Like I said in the post, “noted music critic…” Even better than Allan Bloom!

It’s an outrageous quote, specially because Trent Reznor, Nine Inch Nails’ lead singer and creative mastermind, is not a rapper.

Yes, doesn’t exactly inspire confidence in Bork’s music criticism, does it Kahil? Although, maybe Bork had this Ludacris mix-up in mind?

Wow this was a great post. I was a child at the tail end of all this, so I have almost no recollection of the original controversy surrounding 2 Live Crew. But you’re right, this has had reverberations in the music industry for the two decades since the original debates.

The hip hop genre, by the way, has had its own internal crises over its direction. Everyone’s familiar with the East Coast-West Coast rivalry of the mid-1990s, but perhaps the more important was the debate amongst rappers as to whether or not they should be artistic or go for a more popular audience. This debate is still raging to this day. All that is to say that hip hop is very much like every other form of music, even (ESPECIALLY hip hop) having debates about its place in society. Of course, those debates are magnified by traditional questions in the Black community about art and its utility in regards to social change.

Now that I think about it….the rise of 2 Live Crew and their condemnation by many coincided roughly with the rise of Public Enemy. It’s just something I find fascinating. Finally, in regards to sports (which seems to be my favorite topic on the blog since I first started here, heh) the early 1990s provide an interesting time period to think about race and athletics. Michael Jordan’s rise as an international superstar and the continued arguments about black quarterbacks (Randall Cunningham as well as Warren Moon) in the time period are also interesting case studies in understanding race in modern American society.

Interesting that you brought up Public Enemy, Robert. One of the first rap groups I liked when I was a kid (probably age 13) was 2 Live Crew. (My mom would have been horrified if she knew!) I always knew their songs were jokes, even from that young age. My tastes changed quickly, and I became a huge fan of Public Enemy. In fact, PE is likely one of the main sources of my earlier political consciousness. “911 is a joke in yo town, late 911 wears the late crown.” Ah, so good.

I think an important factor should be added to the discussion: much of the negative attention directed at Sherman on social media and blogs came in the aftermath of a heated, competitive football game. This type of outrage, often racially coded, is common after these kinds of closely contested matches. Just the week before 49ers QB Colin Kaepernick was similarly accused of being a thug and poor sportsman after mocking opposing QB Cam Newton’s signature touchdown dance in the third quarter. In the days after the Kaepernick and Sherman controversies however, I have found the vast majority of public and television commentary has backed off the heated initial public statements into a position most neatly summed-up as “it may have been a bad look from a team sport point of view [overshadowing teammates, disrespecting your opponent, etc.], but it was a product of the heat of the moment and really wasn’t a big deal.”

I think more than the particular instance of Sherman-gate, the problem is why fans reach so quickly for either explicitly racial slights or racially coded criticisms? What does the immediate post game reaction to Sherman’s comments say about the relationship between black players and non-black fans? The NFL has had a race relations problem all year dating back to the Riley Cooper incident in training camp and will probably need to address player-to-player and fan-to-player race relations in the coming offseason.

It will be interesting to see if controversy over Sherman’s post game statements persists or if there are any long term consequences of the event like the 2 Live Crew controversy or if this will get lost in the rapid pace of the sports media cycle as the Super Bowl approaches. I think Sherman is trying to make a statement here about race perception in the NFL (check out his Beats commercial that was recorded pre-controversy, but touches on many of the same themes), but I’m not sure if instigating a controversy of this sort will help or hurt his long term goals of altering white perceptions of black players who challenge white expectations of proper sportsmanship and appearance.

Great points, Matt. I think the controversy is already receding. Except now Sherman has gone and upset Canadiens!

Thank you so much for this really enjoyable, and reflective, post! I would like to press a little on the parody point, though, as your comments really got me thinking.

Gates’s argument about 2 Live Crew seems, to me at least, so remarkably over-interpretive and elusive, so earnest an attempt to gloss those lyrics by detaching the raunchy signifiers from any fleshly signifieds, that it seems as much a moment in the culture wars over Theory as the culture wars over race, or rather one (more) point where those two fused. “Parody” itself slips around a lot in the full op-ed (which for some reason I couldn’t find on NYT, though it is re-published here), while Gates gives 2 Live Crew a surprisingly different treatment in a follow-up op-ed here, responding more to issues of class within the African-American community.

To me, by deploying the “parody” argument, Gates is not just countering the obscenity charge, but also asserting a special public role for Theory: it can mitigate conflict by cautioning us against taking anything literally (his example of Marion Berry in the first op-ed is an acute one here). I think you’re right when you say that it’s kind of beside the point whether 2 Live Crew was rapping parodically in the way that Gates asserts they were: what’s critical for Gates is that we can never be sure. That striking last paragraph of Gates’s op-ed (“This question – and the very large question of obscenity and the First Amendment – cannot even be addressed until those who would answer them become literate in the vernacular traditions of African-Americans. To do less is to censor through the equivalent of intellectual prior restraint – and censorship is to art what lynching is to justice”) offers Theory as a kind of (endless) due process, a check on the urge to adjudicate before all the evidence is in (and it never will be).

Excellent comments, Andrew! I agree, especially since 2 Live Crew lyrics were indeed as raunchy as imaginable, making it hard to think of them in any context other than misogyny. Indeed, this was the crux of Berkeley media critic Ben Bagdikian’s letter to the editor objecting to the Gates op-ed: “Perhaps the language and imagery of 2 Live Crew will someday be as acceptable as scat singing and Jelly Roll Morton and the blues. But perhaps not, because of three elements that make 2 Live Crew’s lyrics different. (1) They are sexist and demeaning to women in ways that are dangerous to the status and safety of women, and are no longer acceptable as clever little jokes. (2) Today those lyrics are broadcast instantly to everyone; they are deliberately not in-group communication. (3) They are not performed as a sequestered inside joke, but mass marketed in the hope of making money rewards precisely because they are promoted to be sensational and clearly understood.”

Gates had a built-in response to this, after calling the group’s sexism “troubling”: “Their sexism is so flagrant, however, that it almost cancels itself out in a hyperbolic war between the sexes. In this it recalls the intersexual jousting in Zora Neale Hurston’s novels.”

You might say that’s Gates over-theorizing 2 Live Crew. On the other hand, I was 14 when I first heard 2 Live Crew–and my ability to think conscientiously about such musical content was about what you would expect from a white, suburban, clueless teenage boy. And yet, I knew it was all a joke, not to be taken seriously.

In any case, the thing that I would accentuate is the hypocrisy issue. I also listened to Andrew Dice Clay at about the same time. And he was just as raunchy as 2 Live Crew, and likely even more sexist, and I was never so sure his sexism was a joke. Yet as far as I know he was never arrested after one of his performances.

Thanks for the response, Andrew! I wish I had been as discerning or as knowledgeable a music listener when I was fourteen–I remember seeing at that age a graffito “Nirvana rocks” and thinking it was advocating Buddhism. And this was in the late nineties.

Having already had my say about this issue on your FB post, Andrew H., I will keep it short here: this post is particularly interesting for me because of the role that canons of taste / hierarchies of aesthetics played in the debate. Following up on Andrew S.’s comment, the testimony of Gates, beyond being perhaps a brief for Theory, was also implicitly and explicitly a legitimation of rap music as “culture” rather than “noise” — that is, as an artistic expression that could be studied with the same critical scrutiny that scholars brought to more “canonical” cultural expressions.

What does it tell us about the cultural politics of race, about the symbols and codes we use to discuss race? What does it say about the current state of American racism?

Is None of the Above one of the possible answers? A few anonymous tweets doth not a race war make. BTW, he was just doing his sports battle rap–goes back to at least Ali.

BTW, anyone who hasn’t caught

http://www.epicrapbattlesofhistory.com/

is in for a treat, esp Key & Peele’s Gandhi vs. MLK. ;-D

I would have to respectfully disagree with Tom in a couple of instances in the above. I don’t think that there’s an all-out race war going on or anything, but I do think that too many folks are content to file away racism as having been solved simply because we don’t have segregated bathrooms anymore. It hasn’t, but it makes the standard white American uncomfortable to talk about and think about it, so we try not to. We fail to connect that certain words and actions have implications and connotations beyond what they literally denote–or we just don’t want to acknowledge the connection because it gives us an excuse to code our outbursts. Maybe we know we’re doing this, maybe we don’t know we are, but we are, in my opinion (see https://s-usih.org/2011/05/more-on-race-obama-and-republican.html)

Allow me an example here: in sports, when a player is called a “thug”, we’ll think of two completely different things depending on whether the recipient of such a charge is white or black. Very rarely do you ever hear about a white guy being called a “thug”, but if you do it’s usually (I have no warrant for this claim, unfortunately) when they are big, routinely physical players (perhaps even nothing more than the hockey equivalent of a “goon”). On the other hand, when you call a black player a “thug”, like Sherman, which is much more common, you’re thinking about gang-affiliation, organized crime, violence, and misogyny. The word is a trope of “West Coast” and “gangster rap”, popularized by Tupac’s “Thug Life” mentality, but twisted to refer to black members of organized crime.

Interestingly, in doing our homework, we see that Richard Sherman actually came from Compton (which, when partnered with Oakland, is widely agreed upon to be the birthplace of West Coast rap, and is also understood to be a “rough ghetto”, and home to much organized crime), graduated high school, graduated college, and is now going to compete in the most popularized annual American sporting event.

If he were white with a history like that, he would be praised for “getting out of the ghetto” and “making something of himself”. His trash talk at the end of the game would have been chalked up to poor sportsmanship.

Just my two cents.

I would have to respectfully disagree with Tom in a couple of instances in the above. I don’t think that there’s an all-out race war going on or anything, but I do think that too many folks are content to file away racism as having been solved simply because we don’t have segregated bathrooms anymore.

Well, do we have a bad guy here? Some caucasian prig who’s pulling the equivalent of a Tipper Gore against sports battle rapping?

Mostly the “controversy” seems to be ginned up by professional sportsgobs/public intellectuals to preen about how “pro-black” they are, pushing against a wall of strawmen, some anonymous twitterers out there.

Flipping by the sports talk radio stations, I catch ex-NFLer Marcellus Wiley approvingly saying Richard Sherman “went gangsta.” As you point out, that’s in the same rhetorical bag as “thug life.” Marcellus thought it was cool.

Mostly, the sharpest criticisms have not been from outraged racemongers, but from Sherman’s fellow Stanford alumni, who are rightfully appalled.

That’s some real USC stuff. ;-P

[BTW, some might enjoy the time-honored/dishonored culture of “sledging” in international cricket.

http://www.smh.com.au/sport/cricket/the-nastiest-sledges-in-cricket-20131125-2y52y.html

Old as the hills…]