The recent exchange at the blog regarding Kathryn Lofton’s statements about intellectual history made me wonder what kind of intellectual history evangelism might be. I thought about this question in light of a short book (or long essay) I am writing on American Franciscan media which has helped me think through how theology, church dogma, and lived religion intersect in media (print and radio to television and the web). One of the lines of debate over Lofton’s interview with Cara Burnidge focused on the problem of democratization–a term that at once seems to evoke derision and heroism among intellectual historians. Dan Wickberg suggests that intellectual historians work on both sides of this term simultaneously and, in a way need to, in order to be honest to both the people we write about and the “thought worlds” in which they exist.

The recent exchange at the blog regarding Kathryn Lofton’s statements about intellectual history made me wonder what kind of intellectual history evangelism might be. I thought about this question in light of a short book (or long essay) I am writing on American Franciscan media which has helped me think through how theology, church dogma, and lived religion intersect in media (print and radio to television and the web). One of the lines of debate over Lofton’s interview with Cara Burnidge focused on the problem of democratization–a term that at once seems to evoke derision and heroism among intellectual historians. Dan Wickberg suggests that intellectual historians work on both sides of this term simultaneously and, in a way need to, in order to be honest to both the people we write about and the “thought worlds” in which they exist.

It seems to me that what I am tracing in Franciscan media presents an example of this sort of interplay, but I wonder if there is term to describe what I see. My question stems in part from a source I have found evocative in my work both on Franciscans and, earlier, on New York movie culture–letters from audience members. These are not letters between recognizable intellectuals or letters that constitute a thought world, but letters between people who read or watch or interact with some kind of media and the people who have some hand in editing or producing the media. Among the best examples of this kind of exchange is one that I posted here a few months ago between a priest named Fulgence Meyer and letter writer identified as Dixie M. Her letter was unique to her particular circumstance but illustrative of a larger, broader condition that many Catholic women found themselves in. Dixie M. explained that she had to endure a marriage that included abject abuse about her past; an indiscretion that her husband used against her in tirades that were loud enough for his entire family and, more tragically, her two young sons to hear. She confessed, “I know that there isn’t any such thing as a divorce for us but I wonder if it wouldn’t be good thing (I mean the best thing under the circumstances) to separate, so that my boys won’t hear such things about me. I am so ashamed of myself and would not want them to grow up thinking that their mother is not a good woman, but a woman to be ashamed of.”

It seems to me that what I am tracing in Franciscan media presents an example of this sort of interplay, but I wonder if there is term to describe what I see. My question stems in part from a source I have found evocative in my work both on Franciscans and, earlier, on New York movie culture–letters from audience members. These are not letters between recognizable intellectuals or letters that constitute a thought world, but letters between people who read or watch or interact with some kind of media and the people who have some hand in editing or producing the media. Among the best examples of this kind of exchange is one that I posted here a few months ago between a priest named Fulgence Meyer and letter writer identified as Dixie M. Her letter was unique to her particular circumstance but illustrative of a larger, broader condition that many Catholic women found themselves in. Dixie M. explained that she had to endure a marriage that included abject abuse about her past; an indiscretion that her husband used against her in tirades that were loud enough for his entire family and, more tragically, her two young sons to hear. She confessed, “I know that there isn’t any such thing as a divorce for us but I wonder if it wouldn’t be good thing (I mean the best thing under the circumstances) to separate, so that my boys won’t hear such things about me. I am so ashamed of myself and would not want them to grow up thinking that their mother is not a good woman, but a woman to be ashamed of.”

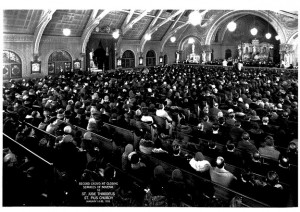

This letter appeared in the November 1930 issue of St. Anthony Messenger a popular, general-interest periodical published by an order of Franciscans in Cincinnati, Ohio. At the time, this magazine was among the most popular Catholic magazines–billed as a family magazine it had sections that appealed to everyone. By 1959 it had a respectable circulation of over 300,000. Undoubtedly, the most popular section of the magazine was the “Tertiary Den” or just “the Den” in which Meyer answered a few of the hundreds of letters he received each week. To Dixie M. he replied: “One would not hesitate to say that her husband is too cruel, heartless, and inhuman a man to stay with. She should serve notice on him that if he ever outrage and insults her in the manner described she will take the children and leave him once for all time. No woman and mother is bound under any consideration to submit to such vile and offensive treatment.”

On the face of it, the exchange is interesting for its personal, almost confessional nature. It is further interesting because it raises the issue of divorce, an idea and an act that attracted a great deal of attention among Catholic officials and critics because of its intimate connection to what has been consistently seen as the most important problem of 20th century American Catholicism, the family. So, Meyer’s reply to this letter and his replies to hundreds of others for over more than decade, constitute an attempt, it seems to me, to inject church teaching and social ethics at a level that met Catholics where they lived. In the essay I am writing I call it evangelizing to the heart rather than the head.

My work echoes the observation made by Robert Orsi in his fascinating portrait of Catholic women and their devotion to St. Jude (the patron saint of lost causes). In his book, Thank You, St. Jude, Orsi reconstructs a culture of letter writing, devotionals, and experiences women forged to manage everything from their romantic relationships to the economic hardship of the Great Depression. A key source for such insight was the letters written to magazines and the national shrine to St. Jude on the south side of Chicago. The vast majority of such letters were from women and, Orsi concludes, the letters reveal a great deal about the lives of the writers: “anger and disappointment with Jude finds expression; deeply felt needs are voiced; the full range of devotional practices are described…and many ways in which women thought of Jude are apparent.”

My letter writers did not speak systematically about ideas or church doctrine but they did write constantly to Meyer and to others such as Franciscan priest Justin Figas in Buffalo who had a radio program in Polish and English that reached a reported 3 million Americans and Canadians, and to the producers of “the Hour of St. Francis” which was the creation of Franciscans in Los Angeles as a radio program first and then as a television program using Hollywood talent that reached tens of millions of viewers.

My letter writers did not speak systematically about ideas or church doctrine but they did write constantly to Meyer and to others such as Franciscan priest Justin Figas in Buffalo who had a radio program in Polish and English that reached a reported 3 million Americans and Canadians, and to the producers of “the Hour of St. Francis” which was the creation of Franciscans in Los Angeles as a radio program first and then as a television program using Hollywood talent that reached tens of millions of viewers.

It is certainly possible to study the ideas that animated the pages of magazines or the episodes of radio and television shows, but it is even more interesting to see how these media became conduits for a feedback loop of evangelism. While I can characterize the thought of these Franciscan evangelizers, I am also struck by the richness of the responses they generated. In the case of Meyer, it became clear to me that the books he wrote throughout the 1920s were a direct reflection of the exchanges he had with his readers in the St. Anthony Messenger. He acted like a Catholic intellectual in certain venues and as a site for a thought world in others. Perhaps this is what evangelism demonstrates to intellectual historians–the interplay between systematic ideas and the democratization of them.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Great topic and reflections here, Ray. I haven’t read this particular book yet (it’s on my summer reading list and Fall class rosters), but Linford Fisher’s the Great Indian Awakening strikes me as an example of evangelism and its popular reception/reinterpretation.

Good stuff. Certainly Fulton J. Sheen and his 30 million viewers figure in here as well.

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/25154593?uid=3739560&uid=2&uid=4&uid=3739256&sid=21103435503413

Ray: Such a rich project. I’m so happy you’re studying this, Ray. I find it interesting as something of a reverse-reception study. You’re dealing with Magisterium teachings as they were communicated, received, and then—most intriguingly—fed back to “teacher” priests. I wonder if the St. Anthony Messenger writers/priests ever found a way to communicate that feedback to the bishops and cardinals, or perhaps even Rome. In the late twentieth century, it’s been that last quarter of the loop that has frustrated thoughtful and sensitive “liberal” Catholics. …Fulgence Meyer sounds like a fascinating object for the intellectual historian. – TL