In his inaugural address, John F. Kennedy mentioned God twice—the more quoted moment comes at the end when he implores his fellow Americans to make God’s work their own. But near the beginning of the address, Kennedy reminds his listeners that there are all heirs to a revolution that continued to echo around the world. “The same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe,” the young president declared, “the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God.”

It was a noble gesture from the newest leader of the free world, whose power lay not, as he went to great pains to emphasize, in his religion or his Church, but in his country. In many ways JFK was a study in the intersection between religion and politics in America. Did religion matter to his presidency? Did it influence his politics, or morality, or strength as a human being? Among the most basic assumptions of American history is that religion matters, but we are often at lost to explain how, as if, like John Kennedy, we’d rather relegate religion that mysterious force that lies just beyond rational explanation and, thus, real influence.

At the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Church History held in Washington D.C., I had the pleasure of commenting on three papers presented by scholars who are in the midst of calibrating out collective understanding of the relationship between religion and politics. They do so fully cognizant of the substantial scholarship on this issue and so offer an opportunity to check on the state of this field. Refreshingly, they start from the premise that religion is not merely, as C. Wright Mills once argued, a dependent variable adapting to the politics of the moment. Each scholar has taken a story that we think we understand and asked new questions thus providing new takes on, respectively, the relationship of Woodrow Wilson’s faith to his politics as manifested in the Covenant of the League of Nations; the relative insignificance of Reinhold Niebuhr in relation to larger institutional changes in American Protestantism; and the origins of Liberation Theology.

More generally, though, this panel gives me a chance to engage the work of three scholars I have gotten know and who in different ways are advancing what seems to me to be part of broader religious turn in academia. Their work will be especially significant to the recent revival of United States Intellectual History.

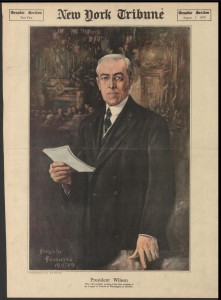

The panel had a chronological order to it, so I will start with contribution made by Cara Burnidge, a recent Ph.D. from Florida State University in Religious Studies. Burnidge’s paper has the most in common with my analogy of JFK, but that does not make her point. She acknowledges that there are basically two schools regarding Wilson’s religion—he was either a preacher-in-chief or a pragmatist who kept his politics and religion separate. While Burnidge does not call upon America’s greatest religious pragmatist, William James, she channels him nonetheless. James understood one could be religious without acting like a caricature of the institutions that formulated religious dogmas and doctrine. Thus in regard to Woodrow Wilson, Burnidge smartly takes stock of the friends the president kept and the discussions about religion he had with them. If discussions about policies matter so do conversations about God. However, it did not follow, then, that Wilson had to insert Godspeak into the Covenant of the League of Nations, after all, it was called a covenant. Wilson understood the League of Nations and, really, the entire World War I in providential terms and that his job, as Burnidge makes clear, was to do God’s work on earth.

The panel had a chronological order to it, so I will start with contribution made by Cara Burnidge, a recent Ph.D. from Florida State University in Religious Studies. Burnidge’s paper has the most in common with my analogy of JFK, but that does not make her point. She acknowledges that there are basically two schools regarding Wilson’s religion—he was either a preacher-in-chief or a pragmatist who kept his politics and religion separate. While Burnidge does not call upon America’s greatest religious pragmatist, William James, she channels him nonetheless. James understood one could be religious without acting like a caricature of the institutions that formulated religious dogmas and doctrine. Thus in regard to Woodrow Wilson, Burnidge smartly takes stock of the friends the president kept and the discussions about religion he had with them. If discussions about policies matter so do conversations about God. However, it did not follow, then, that Wilson had to insert Godspeak into the Covenant of the League of Nations, after all, it was called a covenant. Wilson understood the League of Nations and, really, the entire World War I in providential terms and that his job, as Burnidge makes clear, was to do God’s work on earth.

Burnidge has taken head-on a crucial question: how do we measure the influence of religion in American foreign relations? Do we look for Godspeak and call it a day or do we throw-up our hands recognizing that it would nearly impossible to know whether American policy makers would have made a substantially different history without religious influence? On the face of it, her work appears to echo that of Andrew Preston, whose book Sword of Spirit, Shield of Faith

. Yet it seems to me that Burnidge’s decision to lean toward intellectual history, rather than diplomatic history, pays off, for she finds it significant that Wilson made appeals to religious authority in a way that we take for granted that James was a pragmatist, Herbert Hoover a conservative, and George W. Bush a Texan. In other words, paper trails take us only so far into the culture that a historical actor both responds within and the culture that someone such as Wilson took with him to Europe to negotiate the peace following WWI. Burnidge has established the deep religious culture that moved with Wilson and moved him to act—she doesn’t need a memo from God to make her case.

However, she is charting somewhat new terrain and so it will be instigating discussions about theories that describe the relationships she sees. I will be interested to read about who she finds helpful to explain how religion can operate outside of spaces we have designated as religious. How will we insert religion in the history of American foreign relations without either writing parallel histories of American religion and American foreign policy? In short, the question continues to linger: how we will make religion something more than an afterthought in American historiography?

In his paper, Mark Edwards framed another dominant-subordinate relationship in American historiography: the power the nation-state commands in telling the history of 20th century American religion. In his argument, Edwards notes the uphill battle he has set for himself—the rest of the historical profession spills a good deal of ink legitimizing the nation-state as the most important organizing structure. He blames a good deal of this emphasis on the prominence historians (including me!) have given Reinhold Niebuhr. For Edwards, as important as Niebuhr has been, there are other figures, such as Francis Pickens Miller and Henry Van Dusen, who give historians a chance to speak seriously about the Atlantic World or Transatlantic civil society or ecumenical Protestant internationalism.

But Edwards has a problem with Niebuhr that is important to address. We know that Niebuhr has remained a man for all reasons

and that as the so-called theologian of the power elite he has admirers and detractors. But Edwards wants to suggest that Niebuhr’s power has been so attractive that historians have simply overlooked how out of touch with other, longer-term trends he actual was. David Hollinger made this point quite emphatically in his recent book, Cloven Tongues of Fire, by reminding us just how out of touch Niebuhr had become with an American culture no longer beholden to a certain kind of Protestant mainline power. For his part, Edwards has given us an opening to begin to elevate (or perhaps first discover) other voices in post-war American religious history who mattered. In that project, Edwards does provide something of a cognate to Hollinger’s argument. By taking down Niebuhr a notch or two, Edwards is asking us to consider how Protestantism adapted to the trends Hollinger identified as fundamentally changing the American intellectual landscape.

And so, much like Burnidge, Edwards is proposing a new theoretical approach to American religious history, one that moves the organizing principle away from the nation-state and toward institutions with transnational and even global perspectives. Of course, I don’t question whether Edwards has a valid argument—his evidence substantiates his contentions. In my comments at the panel, I made the pithy remark that avoiding Niebuhr in postwar American religious history is akin to avoiding Lincoln in mid-19th century U.S. history. Not quite a fair comparison, I admit, but as much as there has been a “Niebuhr industry” there has also been a vigorous effort to wean us from our Niebuhr fascination. So my recommendation for Edwards’s project is to account for both the continuing fascination with Niebuhr (why we still seem to have a need for his thought) and the way institutions created a much broader Protestant culture in which to understand Niebuhr’s thought.

The final presenter on the panel was Lillian Calles Barger and her study of development and implications of liberation theology. In the wake of Reinhold Niebuhr’s decline—he no longer graced the cover of Time

The final presenter on the panel was Lillian Calles Barger and her study of development and implications of liberation theology. In the wake of Reinhold Niebuhr’s decline—he no longer graced the cover of Time

in the 1960s—and in the shadow of the rise of the Religious Right, there was a Christian Church with aspirations that extended beyond the borders of the nation-state and had, it seems, little concern for influencing political leaders. The religion that inspired liberation theology was radical, pure and simple argues Barger. Perhaps more than most religious subjects, liberation theologians were hyper-aware of their cultural contingencies—they were the oppressed, or worked with the oppressed and they had few levers of power to pull and resorted to actualizing the radical Jesus rather than accommodating the radicalism of Jesus to modern capitalist society. Clearly this movement offered a bracing alternative to the Protestant Mainline, which had grown relatively irrelevant, or the politically savvy sectarianism of the Religious Right.

I am curious, though, about whether we can call what Barger describes a “movement.” I want to know more about the strands of thought and the periods in which those strands combined to punctuate recent religious history with moments such as the 1973 WCC symposium in Geneva. In other words, can we understand liberal theology through a timeline? In her work, Barger focused on black theologian James Cone, the feminist Rosemary Radford Ruether, and the lapsed liberal Frederick Herzog who insinuated themselves into institutions that would carry forward a broader movement for change and, perhaps, revolution. The ideas of liberation theology also suggest a relationship to other areas of the religious left. So, for example, how does Jim Wallis factor into this story and do the many Protestant colleges and universities serve some role? What is clear is that liberation theology seems to be an amalgamation of post-colonial theories, experience with rights movements, and healthy dose of anti-Americanism. Can we find a core to this movement that we should understand in order to accept it as a historical force in its own right? If so, where is the center of this radical storm?

Barger’s paper sparked a very interesting discussion in the period following the formal presentations because it raised the issue of whether liberation theology can be compared to any other movements or intellectual periods. For example, the conservative movement in twentieth century American incorporated a diverse cast of characters and institutions and even ideas; can we make a similar claim about liberation theology? Barger has a good response to this question, but a bet she would be interested to hear other answers as well.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for posting this, Ray. I don’t have anything substantive to say about the panel or the papers (not having read or heard them). But perhaps you and potential readers of this post are game for a question related to the liberal theology mentioned at the end of your comments on Lillian Calles Barger’s paper.

While writing recently on the conversion(s) of Mortimer J. Adler (article drafted), I ran across references to Adler’s intense reading in the works of the Episcopalian “Bishop Spong” (aka John Shelby Spong, more here).

What is known about the reach of Spong’s work? What historians of religion have written on him or his work? Is he in any way related (substantially) to Wallis, Cone, or Ruether? – TL

Tim, without going into detail about the fragmentation of liberal theology in the 1960s and 70s and its after affects, I would say all these theologians are within the currents of post-enlightenment modern theology and share many intellectual antecedents. Each, taking up a different aspect of those trends, responded to their contemporary situation. The main idea liberationists share with Spong is of transcendence collapsed into immanence.

First generation liberationists were political theologians concern with a radical change in the social order rather than reformulating doctrine. They would reject Spong’s highly theoretical constructions that do not take into account how oppressed people experience God. James Cone and black liberationists challenged the interpretation of the text, rather than the text itself as Spong does, that did not question the social (elite white) position of the theologian. Ruether went further than male liberationists by questioning the text itself. It was not just the interpretation that was problematic, but also the biblical male authors expressing a patriarchal and misogynistic mindset. Many feminist theologians embraced the positions held by Spong. Wallis is of the evangelical left appealing to the social justice tradition of the 19th century evangelical reformers and I would not count him among the liberationists but he is their sympathizer.

The study of how these religious intellectuals built their ideas from various streams of modern thought, the differences among them, and their wide cultural influence is ripe for examination by intellectual historians.

Thanks Lillian, for the larger context. Your point about challenging the text v. the interpretations of the text is well taken. – TL