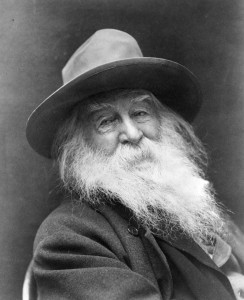

A recent anti-intellectual screed published in my local community paper suggested that historians do nothing more significant than inquire into the length of Walt Whitman’s beard. I took this insult as something of a challenge, and uncovered fascinating material regarding Whitman’s beard as a symbol, particularly of the poet’s “homosexuality.”1 Beyond Whitman, beards and facial hair in general have served as powerful cultural symbols for communicating sexuality, manhood, insanity, and divinity in American history.

A recent anti-intellectual screed published in my local community paper suggested that historians do nothing more significant than inquire into the length of Walt Whitman’s beard. I took this insult as something of a challenge, and uncovered fascinating material regarding Whitman’s beard as a symbol, particularly of the poet’s “homosexuality.”1 Beyond Whitman, beards and facial hair in general have served as powerful cultural symbols for communicating sexuality, manhood, insanity, and divinity in American history.

The Spanish poet and playwright, Frederico Garcia Lorca, spent the year 1929 in New York City, where he wrote a number of poems including “Oda a Walt Whitman.” Addressing “viejo hermoso Walt Whitman”—beautiful old Walt Whitman—Lorca wrote that “los maricas te soñaban”—the Queers dreamed of you. “¡También ese! ¡También!”—he is one too, they say! “And they tumble,” continued Lorca, “on your luminous, chaste beard.” “Not for a moment,” the Spanish poet confessed to “viejo hermoso Walt Whitman,” “have I failed to see your beard full of butterflies”—“tu barba llena de mariposas.”2

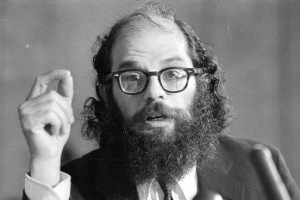

For Lorca, Whitman’s beard identified him as a marica. Allen Ginserberg, who used Whitman as a model for his poetry, his sexuality, and perhaps also his facial hair, similarly identified the poet’s beard with his homosexuality. Lorca and Whitman appear together in Ginsberg’s poem “A Supermarket in California,” published in 1956 in Howl and Other Poems.

What thoughts I have of you tonight, Walt Whitman, for

I walked down the sidestreets under the trees with a headache self-conscious looking at the full moon.

Ginsberg opens this remarkable poem addressing Whitman, and a few lines later he addresses Lorca.

In my hungry fatigue, and shopping for images, I went into the neon fruit supermarket, dreaming of your enumerations!

What peaches and what penumbras! Whole families shopping at night! Aisles full of husbands! Wives in the avocados, babies in the tomatoes!–and you, Garcia Lorca, what were you doing down by the watermelons?

“Where are we going, Walt Whitman?” asks Ginsberg in this poet’s meditation on  queerness, loneliness, and queer loneliness in America. “Which way does your beard point tonight?” “Will we stroll dreaming of the lost America of love / past blue automobiles in driveways, home to our silent cottage?” Ginsberg asks his silent companion, addressing him finally: “Ah, dear father, graybeard, lonely old courage-teacher.”3 Here, again, Whitman’s beard is a symbol of homosexuality, but for Ginsberg, the beard also paints Whitman as a father figure, a wise old teacher.

queerness, loneliness, and queer loneliness in America. “Which way does your beard point tonight?” “Will we stroll dreaming of the lost America of love / past blue automobiles in driveways, home to our silent cottage?” Ginsberg asks his silent companion, addressing him finally: “Ah, dear father, graybeard, lonely old courage-teacher.”3 Here, again, Whitman’s beard is a symbol of homosexuality, but for Ginsberg, the beard also paints Whitman as a father figure, a wise old teacher.

In his poem “Defending Walt Whitman,” published in 1996, Native American poet Sherman Alexie imagines Whitman enjoying a somewhat erotic game of basketball with American Indian boys. “His huge beard is ridiculous on the reservation,” Alexie describes.

He is a small man and his beard is ludicrous on the reservation, absolutely insane.

His beard makes the Indian boys righteously laugh. His beard

frightens the smallest Indian boys. His beard tickles the skin

of the Indian boys who dribble past him. His beard, his beard!4

“His beard, his beard!” From Lorca, to Ginsberg, to Alexie, Whitman’s beard is his sexuality, his genius, and a symbol of his self.

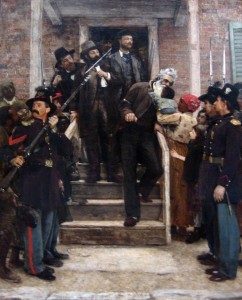

Turning from poetry to painting, another nineteenth century beard has become famous in American culture. Abolitionist John Brown only grew a beard for a few months of his life. Only one photograph exists of him with a beard; several depict him without facial hair, including during the time of his raid on Harper’s Ferry. Nevertheless, there is almost no image of Brown in paint or in print that shows him without a long, wild beard. The image of Brown with a tangled beard may well be linked to the idea of Brown as insane, a charge invented by his defense lawyer and spread by southerners and nervous northern moderates. With a long unkempt mass of hair beneath his chin, Brown does look the part of the zealous lunatic.

In Thomas Hovendon’s sympathetic painting, The Last Moments of John Brown (left), completed in 1884, however, Brown’s soft white beard against the check of the young black child he leans forward to kiss makes him appear fatherly and even god-like.

In Thomas Hovendon’s sympathetic painting, The Last Moments of John Brown (left), completed in 1884, however, Brown’s soft white beard against the check of the young black child he leans forward to kiss makes him appear fatherly and even god-like.

Brown is also depicted as a god figure in John Stueart Curry’s Tragic Prelude (below) completed in 1940, but this god is a vengeful god. With his larger-than-life beard blowing violently to one side, this John Brown looks like an angry Zeus, or perhaps he is Moses, also bearded, parting the seas.

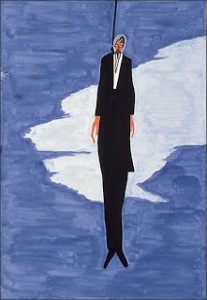

Brown wears a beard throughout Jacob Lawrence’s series of twenty-two prints depicting Brown’s life and abolitionist efforts. In the final of these prints (below), Brown’s beard is perhaps his most distinctive feature.

It is not surprising that Whitman’s and Brown’s facial hair should carry such important symbolism. Indeed, in American Nietzsche, Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen discusses the importance of the images produced and reproduced of Nietzsche—was that mustache a sign of his madness, his genius, his German-ness?5 The best exploration of the meaning of facial hair in American culture can be found in Kristin L. Hoganson’s masterful Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, published in 1998.

Hoganson demonstrates the deep gender anxiety seeping out of every aspect of American life and framing political debates in the lead up to the Spanish-American War. Although she stops short of arguing for gender anxiety as a cause of the war, her evidence would allow her to make that argument powerfully. Among the ways in which Hoganson sees gender anxiety invading political discourse are demeaning depictions of President McKinley by those who believed the President was failing to take a strong stand against Spain. Hoganson presents cartoon after cartoon featuring McKinley in a dress or with a rattle, or both. He is a woman, and a baby, or a baby girl, the opposition cried! At the center of anxiety about their President’s manhood, Hoganson argues, was his lack of facial hair. Every President since Ulysses S. Grant had sported some kind of facial hair— from Chester Arthur’s fancy muttonchops, to Grover Cleveland’s simple mustache. Clean-shaven McKinley, however, had put his gender identity up for question by failing to grow hair on his face.6

From this small amount of evidence, it does seem that if all historians did was discuss beards in the past, we would still have a window into ideas about gender, sexuality, madness, justice, politics, and war.

__________________________________________

1 In Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (1996), David S. Reynolds convincingly demonstrates that “homosexuality” is an anachronistic term to apply to Whitman, but I am mostly concerned here with how Whitman was used as a symbol of homosexuality for later writers.

2 Frederico Garcia Lorca, “Oda a Walt Whitman” <http://writing.upenn.edu/library/Lorca-Garcia_oda-a-walt-whitman.html> an English version may be found here <http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/ode-to-walt-whitman/>

3 Allen Ginsberg, “A Supermarket in California,” <http://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/88/supermarket.html>

4 Sherman Alexie, “Defending Walt Whitman,” <http://www.bpj.org/poems/alexie_whitman.html>

5 Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, American Nietzsche (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 2012, 52-53.

6 See Kristin L. Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (New Haven and London: Yale University Press), 1999.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

http://50watts.com/Poets-Ranked-By-Beard-Weight

Excellent! Thanks for this, Rivka.

Let us notice also the periods where our male cultural symbols are without beards: the 1920s, the 1940s, and especially the 1950s (Elvis, Dean, MLK, and on and on). After a period of facial hair popularity in the late 1960s and 1970s, then we see the return of clean faces in the 1980s.

Facial hair, if not beards always, can also be about power. Think of the males often depicted as iconic for the Black Power movement, meaning their goatees and mustaches. And then there’s Malcolm X’s transition from Nation of Islam and a clean face to traditional Islam and the beard. So the facial hair is about a conversion, but also in tradition with Islamic male attire. – TL

Remembering our “Feuerbach vs. Marx” beard discussion from several years back… Perhaps you could crack that open in the sequel to this post?

So what does it say that we haven’t had a bearded president in a century? What about bin Laden’s beard?! And then there is this:

http://www.nationalbeardregistry.org/beards/famous.asp

Beards as connected to authority and propriety also have a religious aspect–look at the unbroken line of beards in Mormon prophets from Brigham Young through George Albert Smith. I’m not sure offhand when Young grew his beard, but the LDS bearded period lasted from somewhere around 1850 to 1951, far longer than the era of “the bearded ones” occupying the White House, and crossing over the beardless social periods that Tim mentions above. It makes sense that a religious tradition that depends on unbroken lines and direct connections to ancient times would hold on to the beard more resolutely than the rest of the nation, but it’s also interesting to see the power of the 50s and the renewed push to be seen as full participants in the American experience. The dual LDS institutions of the church hierarchy and Brigham Young University excluded beards for missionaries, leaders, and BYU students, and thus set a standard for the rest of the church. There is no explicit proscription on beards, but it is understood that leaders are clean-shaven, so as you go from local rank-and-file up the hierarchy, beards become less common very quickly, even while every Mormon knows that for a hundred years, their leaders wore beards, some of prodigious length and/or volume.

Very interesting post! The beard seems to be one of those extraordinarily flexible signifiers–representing everything from patriarchal domination and religious orthodoxy, on the one hand, to counter cultural and bohemian inversions of dominant authority–sometimes, but not always, in sexual terms. And these seem capable of coexisting in the same culture at the same time. One issue you didn’t touch on is the idea of the beard as a kind of disguise or mask. This meaning is, for instance, involved in the slang term “beard” as a designation for a fake opposite-sex partner used to disguise homosexuality. What do you make of that usage, given the idea that for Ginsberg and Whitman the beard was a signifier of homosexuality, rather than a way to disguise it?

There was an article in the AHR a few years back on “wig history,” but I’m not sure we’ve yet seen the historiographical move to facial hair! Next up: the history of the hat!

Oh, also given the title of your post, I was hoping to find that Frederick Jackson Turner was bearded, but, alas, it appears that he only had a mustache–perhaps at the point where savagery met civilization (I think that’s the upper lip!).

Submitted without further comment: http://books.google.com/books?id=sqIzLgEACAAJ