How one reads a text—including how one evaluates the aesthetic merits of a text—is almost entirely dependent on a host of factors that, taken as a whole, are best summed up in a word: context. This is an obvious point. Nonetheless, let me give an example.

How one reads a text—including how one evaluates the aesthetic merits of a text—is almost entirely dependent on a host of factors that, taken as a whole, are best summed up in a word: context. This is an obvious point. Nonetheless, let me give an example.

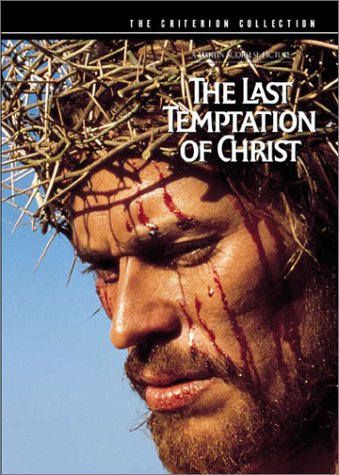

I’ve now watched Martin Scorsese’s 1988 picture The Last Temptation of Christ twice. My first screening was five years ago, my second, a few days ago. Based on more knowledge of the film and the controversy that engulfed it—based on more context—my judgment of the movie has changed.

The first time I watched The Last Temptation of Christ, my assessment was similar to conservative film critic Michael Medved’s: “It is the height of irony,” Medved told a television reporter, “that all this controversy should be generated by a film that turns out to be so breathtakingly bad, so unbearably boring.” Like Medved, Harvey Keitel as a heroic Judas left me cold. Medved panned: “With his thick Brooklyn accent firmly intact, braying out his lines like a minor Mafioso trying to impress his elders with his swaggering, tough-guy panache, Keitel looks for all the world as if he has accidentally wandered onto the desert set from a very different Martin Scorsese film.” This was exactly my initial reaction: Scorsese had rendered a “Goodfellas” edition of the Gospels. It was laughable.

My view of the film has changed as I learned more about why Scorsese made it, and what he put into its making. Scorsese had been obsessed with making a film based on Nikos Kazantzakis’s 1955 book, The Last Temptation, for over 15 years. Scorsese grew up a devout Catholic and remained fascinated with Christian symbolism even after he quit attending church. He was taken with Kazantzakis’s post-Enlightenment, Nietzschean Jesus, a Christ who created his own meaning. Scorsese, like Kazantzakis, wanted to emphasize the human side of Jesus, flaws and all, in order to make Jesus relevant in our contemporary, corrupted world. As part of this mission, Scorsese wanted a proletarian version of Judas, who was the hero in Kazantzakis’s revisionist tale. For Scorsese, working class heroes hailed from Brooklyn.

Scorsese’s commitment to making this film was evident in the hardships he overcame along the way. For example, Paramount, the first studio to purchase the rights to produce the film, canceled production at the last minute due, in part, to a groundswell of conservative anger that a movie was being made about Kazantzakis’s controversial novel. In the years between when Paramount cancelled the film and when Universal Studios agreed to make it, Scorsese made several more mainstream films in order to buy freedom to make The Last Temptation, his true labor of love.

All of which is to say that my second viewing of The Last Temptation of Christ was through a different lens. I came to the film with more respect for Scorsese’s vision. It’s hard to explain, but because of such contextual knowledge, I truly enjoyed watching the film the second time. I was better able to make meaning of it.

————–

For a great account of the making of the film, and the controversy, see Thomas R. Lindlof, Hollywood Under Siege: Martin Scorsese, the Religious Right, and the Culture Wars.

And for a snapshot of the controversy, see this Oprah episode.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’ve only seen this movie the once..and it was back in high school. I intend on revisiting it someday. I remember that I found it interesting, but not quite as good as it could have been.

That’s probably a decent assessment, Kevin–interesting, but could have been better. Ultimately, the context that informs how we judge the merit of a film or any cultural production is left implicit. But in the case of my second viewing of “The Last Temptation,” the context became much more explicit, and thus altered my perception a great deal, in ways that I was alert to.

I think your point is particularly relevant in artistic endeavors that don’t rely on words. I’m thinking of Shostakovich’s 7th symphony “The Leningrad”, whose introductory and controversial march sequence, an otherwise dull and monotonous theme, is resurrected with the knowledge that it represents the inexorable march of the German army toward Leningrad; or the alternate explanation, therefore the controversy, that composer intended it as a comment on Stalinist forced industrialization. Either explanation gives this piece a context with which to listen to the music and try to envision its significance.

Great example, Paul–thanks!

Andrew: What do you know about the reception of Nikos Kazantzakis’s 1955 book? Did it receive much attention from conservatives like Buckley, Russell Kirk, Catholic intellectuals, or members of the John Birch Society? – TL

Tim: The 1960 English translation was very controversial. Conservatives attempted to have it banned from their local public libraries in several US regions, including Orange County. The John Birch Society was involved in such efforts–and this history could have been included in Lisa McGirr’s “Suburban Warriors.” I don’t have any knowledge of whether conservative intellectuals like Buckley or Kirk commented on the book. The Catholic Church officially denounced it.

Thanks. I was looking for consistency, over time, in conservative denunciation. You’ve answered that. There was some history.