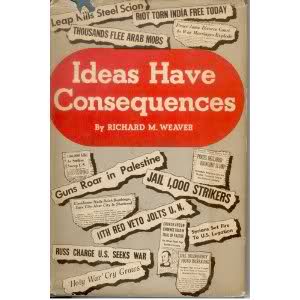

One of the interesting things about Richard Weaver’s Ideas Have Consequences (1948) is the dust jacket for the first edition.

The cover art features an assortment of headlines “ripped” from the front page of newspapers — “Thousands Flee Arab Mobs,” “Riot Torn India Free Today,” “Girl Delinquency Found Increasing,” “Guns Roar in Palestine,” “11th Red Veto Jolts U.N.” — and scattered across a gray background in an off-kilter collage of Really Bad News. Not superimposed over these grim headlines, but crowding them out and pushing them aside is a large oval of bright red, like a great big pill. Against that red lozenge the title of the book appears in bold white font, delivering a much-needed dose of truth to explain, if not to cure, the malaise of the era manifested in the headline news.

In a meta-modern move, print advertisements for Weaver’s book that ran in newspapers reproduced the cover art beneath headlines which discussed the headlines. This was the case, for example, in an ad in the New York Times book review section of March 14, 1948 (p. BR17). The top half of the ad pulls some of the more alarming headlines from the book cover — girl delinquency is right up there with mobs and strikers — and asks the newspaper reader “If you believe our civilization is the most advanced in history — how do you explain these headlines?”

In a meta-modern move, print advertisements for Weaver’s book that ran in newspapers reproduced the cover art beneath headlines which discussed the headlines. This was the case, for example, in an ad in the New York Times book review section of March 14, 1948 (p. BR17). The top half of the ad pulls some of the more alarming headlines from the book cover — girl delinquency is right up there with mobs and strikers — and asks the newspaper reader “If you believe our civilization is the most advanced in history — how do you explain these headlines?”

The ad copy helpfully tells the reader what to make of them:

“These headlines are symbols of our civilization…bomb-shattered cities, stricken faiths, world-wide misery and disillusion. What’s at fault? Who’s to blame? IDEAS HAVE CONSEQUENCES will tell you. The answer may shock you. It may also start you on the road toward changing these headlines….” And so on.

What makes the headlines in question “symbols of our civilization” is, according to both the advertisement for Weaver’s book and the argument of the book itself, the “misery and disillusion” they record and report. Basically, everything has been going to hell in a handbasket ever since the snake of Nominalism got loose in the West’s epistemic garden, and the only thing that will save the world from a disastrous future is a return to the distinctions of the past.

But beyond its value as an easy way to symbolize a world in disarray, the newspaper theme of the cover is also in keeping with the important role the newspaper plays within Weaver’s text. In his diagnosis of what ails the modern era, Weaver points to the press — along with film and radio — as the moving parts of the Great Stereopticon, a three-part media machine projecting its malignant metaphysical vision upon the walls of the communal cave. This configuration of Weaver’s Stereopticon dates the book as a relic of the pre-television era. Had he been writing a decade or fifteen years later, Weaver’s machine would almost certainly have included a fourth moving part, television — though “radio” might have morphed into “music industry,” or perhaps (as in Allan Bloom’s version of Everything Wrong With Kids These Days) more specifically, “rock and roll.” But even if Weaver had written that book as much as thirty years later, the Press would still have formed a necessary part of his modern media machine.

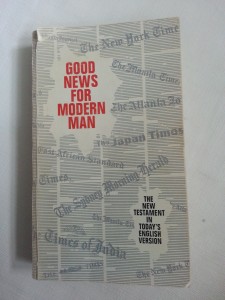

The newspaper as the emblematic medium of modernity appears on the cover art of a very different text from a somewhat later post-war moment, the American Bible Society’s 1966 translation of the New Testament, Good News for Modern Man. While the text was published as a pew bible — black boards, gilt lettering, etc. — it was more widely and more notably available as a 25 cent paperback, cheap and portable.

The cover art for the paperback renders the newspaper form abstractly as grey columns of full-justified lines, broken up here and there with line breaks and indentations. Spanning the grey columns, but misaligned horizontally in a haphazard scattering, are the grey nameplates of English-language newspapers from around the world, in several font sizes: The Sydney Morning Herald, The Japan Times, the East African Standard, the Times of India, The Manila Times, The Times of London. The Grey Lady herself spans three columns across the top of the cover.

The cover art for the paperback renders the newspaper form abstractly as grey columns of full-justified lines, broken up here and there with line breaks and indentations. Spanning the grey columns, but misaligned horizontally in a haphazard scattering, are the grey nameplates of English-language newspapers from around the world, in several font sizes: The Sydney Morning Herald, The Japan Times, the East African Standard, the Times of India, The Manila Times, The Times of London. The Grey Lady herself spans three columns across the top of the cover.

Breaking through this uniform greyness via a “torn” section in the upper left corner of the newspaper design is the title of the book in block red letters: Good News for Modern Man. A smaller “tear” at the lower right corner contains the subtitle in black: The New Testament in Today’s English Version.

The newspaper theme of the cover art provides a visual pun on the translation’s title and aim. “Good News” is a literal translation of the Greek word (euangelion) previously rendered as “Gospel.” In contrast to the dreary grey reportage of the daily newspapers, filled with bad news from around the world, this modernized translation “reported” the good news of God’s love for humankind — a breaking story, as it were, as current as the day’s headlines.

But the newspaper theme also gestured toward the translation’s aim to render the text of the Bible in accessible prose. The Greek of the New Testament — koine (“common”) Greek — was the Greek of the marketplace, the Greek of the street, the language of hoi polloi. It was the lingua franca of the Mediterranean basin in the first century AD, ubiquitous and accessible. The purpose of the TEV translation was to render the Bible into English that would be similarly accessible to an international readership. This was to be an English free of archaic turns of phrase or regional idioms, the kind of English being taught and acquired as a second language in schools and universities around the world, resulting in a Bible written in the lingua franca of the post-war and (emerging) post-colonial era.

So, in search of a visual representation for either relevance or accessibility, the cover art of Good News for Modern Man drew upon the newspaper. Weaver’s book also attempted to assert the relevance of ancient truths for modern times in an accessible way, and the cover art for his book reflects that popularizing tendency as well. But there are other ideational affinities between Weaver’s book and the ABS translation of the New Testament, other reasons why visual invocations of the newspaper as a medium may have served as an especially apt illustration for both covers.

If the conviction that present woes can be explained (or survived) by a return to ancient truths is common to both, they also partake of an underlying sense of apocalypticism. The newspaper motif of both covers visually conveys the idea that the present is a thin wrapper through which both past and future are breaking through with dreadful power.

Post-war evangelical missiology was informed by a sense of eschatological urgency, and Bible translation and Bible distribution lay at the heart of of evangelical mission efforts. The centrality of Bible distribution to mission efforts is an idea that has carried over from the era of the Good News Bible into current evangelical thinking. (It was part of evangelical thinking before the era of the GNB, but that’s a subject for another post.)

Some evangelicals believe that the Lord will not return until the “Good News” has been preached to the whole world, so it is the task of the church to hasten the Lord’s coming by seeking converts from “every tribe and tongue and people and nation,” in the words of Revelation. This idea seems to be a basic underlying rationale, for example, for much of the work undertaken by the U.S. Center for World Mission at Fuller Theological Seminary. Other evangelicals believe that the Lord’s return is imminent, and so it is urgent to carry the message of Christianity to as many people as possible — though preferably in their native languages — so that they can be saved from the judgment to come. This idea seems to be the underlying rationale of Wycliffe Bible Translators. In any case, evangelical missiology has long drawn a close connection between the worldwide distribution of the scriptures, the worldwide proclamation of the Christian message, and the end of time.

The end of time itself has been a particular preoccupation with a large and growing segment of evangelicals, as Paul Boyer makes clear in his absolutely indispensable study, When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern American Culture (Belknap/Harvard, 1992). Among other things, Boyer’s book highlights the tendency of “prophecy popularizers” to find in the details of news reports and current events the fulfillment of various cryptic clues in prophecies related to “the end times.” One speaker at a prophecy conference in 1967, for example, declared that a glance at the daily newspaper would confirm in current international events the emergence of the One World Government among the Western nations, with the United States playing the leading role (277).

While some preachers found in the newspaper a fulfillment of things promised or a portent of things to come, most pastors, evangelical and otherwise, doubtless used the newspaper in much the same way that they use various media today — as a source for sermon illustrations, as a way of connecting the preaching from the pulpit to the life in the pews, as a bid for relevance.

A statement to the effect that pastors could make their sermons relevant by preaching with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other has been attributed to both Karl Barth and Billy Graham. In 1963, Barth told a Time reporter that in the 1920s he used to advise young theologians to “take your Bible and take your newspaper, and read both. But interpret newspapers from your Bible” (“Barth in Retirement,” May 31, 1963, p. 60). In 1985, Billy Graham told the American Newspaper Publishers Association convention, “I believe a preacher worth his salt holds up the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other….If your paper reports the issues, the Bible reports the issue behind the issues.”

But the idea of a connection between the Bible and the newspaper — whether the connection grows out of the pastoral role of making sermons relevant or the prophetic role of interpreting the signs of the times — is original to neither Barth nor Graham. Instead, they were both drawing upon broadly held notions of relevance — not only the relevance of “Bible truths” for contemporary life, but also the relevance of the newspaper as the defining medium of their time.

In a similar way, the cover art of both Weaver’s volume and the New Testament translation effectively date both books to an era when everyone got the punchline of the joke, “What’s black and white and read all over?” That is to say, everyone got the humor and

— or, because — everyone got the paper.

But the times — and The Times — have changed. Whatever age is dawning, the age of the newspaper belongs to history. And — perhaps — vice versa.

16 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Can someone explain nominalism to me in a few sentences?

Now that I think about it, that’s an interesting problem — can I say what nominalism is in any absolute sense, or just what it has meant historically? What it meant to Weaver, who roots his discussion in the history of philosophy, was an epistemology (derived from the work of William of Occam) that denies such a thing as (abstract) universals — truth, humanity, goodness. Our names for such things do not correspond to a reality external to the naming of the things. For Weaver, the denial of absolute truth has been a corrupting influence in morality, politics, the arts. The Impressionists were decadent because they didn’t believe lines existed in nature, etc. The denial of absolute truths leads (in Weaver’s thinking) to absolute relativism. If there is no absolute standard, then there are no standards, period. Aesthetic judgment goes out the window, virtue goes out the window, culture is undermined from below, etc.

Have you seen the Jack Van Impe show? His wife reads the terrible news events happening across the world and he interprets the meaning from his reading of biblical scripture. The “Good News” element is alive and well in this show it not only confirms the biblical foreknowledge it invariably has a happy end of times resolution.

I haven’t seen that cover of the Good News Bible since my own copy in parochial school in the early eighties, but that sure brings back memories.

My favorite examples of mining the newspapers for pointers toward and proofs of prophecy are the columns in Pentecostal newspapers in the early 20th century that collected news clippings from all over the world that in some way connected to an end times prophecy. One of the popular columns was at times titled “The Outlook and the Uplook,” the outlook being the description of the bleak reality of the world, and the uplook being the prophetic interpretation of these events that promised an imminent second coming.

I just have to say this was a joy to read. And, being someone who has written a good deal about print media in both the late 19th century ( I analyzed coverage of the Populists in the 1896 elections in Georgia newspapers for my MA thesis) and in the 20th century (working on partisan magazines in the 1960s-1990s and their construction of Civil Rights/Black Power memory for the public sphere) I’m always thinking about how future generations will, or will not, interact with print media.

I also wonder how much future generations of historians will look to newspapers as leading arbiters of opinion in our era. They’d probably have to consult leading blogs just as much to get a grasp on what leading thinkers (especially those on the American Left and Right wings) were talking about.

Thanks all for the thoughtful comments.

You may have noticed that the post ended rather abruptly. This was not intended as a mimetic nod to the rapture — I just realized that if I didn’t break off where I did I would be looking at another 1800 words. This was a long read as it is.

I would have spent a second 1800 words exploring the connection between the newspaper and modernity (as posited by Benedict Anderson) and the philosophy of history (including the eschatological impulse coursing through both Hegel and Marx). In brief: it seems to me that a way of thinking about the past that emerged with the newspaper and that has unfolded in a world ordered by newspapers might undergo some kind of change if the world of the newspaper vanishes. In other words, Robert, I think when the newspaper goes, a mode of historical thinking may go with it. This doesn’t imply some narrative of declension — just a suggestion of a deeper change than we who are in the midst of it might be able to perceive.

The articles on Billy Graham and Karl Barth are interesting because both of them comment explicitly on the role of the press in society — Barth’s assessment comes close in some ways to the judgment of Weaver on the importance of the press.

Also, as Charles indicates, the GNB (the OT translations was completed in 1976) has been used for far more than just international missions. I spent all my time on the cover art, but didn’t even mention the marvelous and instantly recognizable artwork inside the Bible — simple, elegant line drawings (with some occasional surprising details). Some of the drawings are quite lovely, while others are absolutely hilarious. (There’s a very literal illustration for the figure of speech from the epistles of Peter, “A dog returns to its vomit, a pig goes back to its slop.”)

After reading the final paragraph of the first half of this post, the one that summarized Weaver’s book (the Great Stereopticon), I thought the thread—even if just gossamer—would turn toward the modern conservative vision. That vision is, in fact, propounded by the Great Stereopticon (FOX News, Limbaugh, and the WSJ—film has been something of a failure for conservatives) rather than castigated by it. Of course Weaver was a traditionalist, and traditionalist conservatives have been drowned out by Randian individualists (Ayn, not Rand Paul), so my proposes, very-thing thread fails in obvious ways. But it’s interesting to ponder that old books and timeless truths seem to matter less to today’s latte-chugging, blog-writing, sound-bite providing conservatives. Today the Stereopticon is in their service, and therefore cannot be as much a foil for their apocalyptic prophecies. But hey, this is just me in Saturday night speculative mode—improvising on LD’s riffs.- TL

Tim, that shift from “Great Books” to “no books” is one of the things I am looking at in my dissertation. I have my theories…

Paul, on your recommendation, I dutifully watched some Jack Van Impe “news and commentary” episodes on youtube. Yes, I have flicked past this guy before. He is a key source in Boyer’s book, and a good example of this notion of time in which the barrier dividing the present between the ancient past and some final future is as thin and flimsy as newsprint, the nightly news is a palimpsest beneath which we can read the eternal decrees of God, etc.

Boyer does such a good job of laying out some of the logic of this belief system and exploring some of its implications for politics, diplomacy, etc. The book is a tour de force in intellectual history written with intellectual sympathy. Boyer’s patience — to look at this subject so deeply and so long, and to write about it without caricature or contempt — is beyond impressive.

L. D.,

This is a immensely fascinating post, and your comments illuminating what further thoughts you had are just as exciting.

Have you given any thought to the developments the Left Behind series might allow for these ideas, especially in regard to eschatology? One of the principal characters is a journalist who mixes print and on-line journalism, and the Antichrist’s ability to control the media is, I believe, a major theme. (I am committing the S-USIH cardinal sin and discussing a work i haven’t read, but I couldn’t resist making this connection.)

Andrew,

Alas, at the urging of a friend who was reading them, I read all of the Left Behind books. Happily, I have forgotten almost all of the plot details, including the journalist angle. Thanks for pointing that out.

It might be interesting to look at how the books portray the relationship between print culture and online media, especially since they were being written/published during a long liminal moment of transition from the newspaper to the web as a principal source of news. As Boyer demonstrates, pop apocalyptic has long expressed anxiety about the role of computers in the rise/reign of antichrist. But I wonder if some inchoate sense of a deep shift in the foundational world of print might be behind some of the particular developments in the LaHaye/Jenkins series — not that this anxiety has stood in the way of the various online/computer derivations of their work, including a Left Behind video game and god knows what else.

However, I’m having enough trouble right now making myself read Bloom, Bennett, Kimball and D’Souza — the Four Horsemen of the Western Civ Apocalypse. I don’t think I could stand to do a close reading of Left Behind any time soon.

I completely sympathize with that response, L. D. I certainly would try to swing wide of reading such a mountain of purple prose if I could.

What I think is fascinating about the Left Behind phenomenon is precisely that tension you identify–I think LaHaye certainly wanted to use print media rather than some other platform to reach a large audience, and firmly believed in that as a prudent tactical choice, but the success of the book series proved too great a temptation not to franchise out into other media platforms.

LaHaye and Jenkins’s treatment of the power of the media in the Left Behind series is, like many themes in their trainwreck of a work, a study in contradiction between showing and telling. The reader is constantly told that Buck, the journalist character, is a phenomenal reporter, known worldwide for his investigatory acumen, but he doesn’t manage to file a story on the rapture for weeks after. When he is given complete and total access to the most powerful man on the planet (spoiler: it’s the Antichrist!), he doesn’t reveal anything he learns. Likewise, the Antichrist’s control of the media is all-encompassing, or so we are told. As with the logistics of a one-world government (except Israel) and a one-world currency/language/religion, the authors consistently forget that the Antichrist controls all media, and thus it is useless as a tool.

For the authors, the idea of news media is a threat to power, but it never goes beyond that. It is a gun that never gets pulled down from the mantle. This may be because the events of the books are happening during the end times; the people living in a post-rapture world no longer need to search the newspapers for evidence of the signs of the times; they are all around them already. Thus, the true purpose of the media has already been fulfilled. There’s no point in reporting anything anymore when the apocalypse is playing out on schedule.

Great piece!

A few comments:

1. The missiology that connects worldwide distribution of the message of the gospel and the end of time was also very important, interestingly, to the first generation of Pentecostals and their belief that tongues were foreign languages given specifically for the purpose of missions.

2. Matt Sutton, in his work on apocalypticism and evangelical/fundamentalist opposition to the New Deal, has turned up some amazing examples of “Bible in the one hand, newspaper in the other.” Including some missionaries meeting with Mussolini to tell him how his rise was foretold by the Bible ….

3. When I went to Hillsdale College in 2001, Weaver’s title was regularly invoked to justify *ignoring* the present in the curriculum. The school’s general studies requirements were designed by Russell Kirk and adamantly great books, dead white men, etc. Weaver’s book wasn’t read, but it was mentioned a lot (more than Bloom), and justified the approach, as well as the idea that history was really most essentially intellectual history.

Based on what I discovered about strains of great books thought while exploring M.J. Adler’s life and writings, it seems to me that the flavor of great books idea utilized by Hillsdale falls somewhere between what I call “Great Books Conservatism” (use of GBs to fortify traditional values against perceived moral relativism), the “Strauss-Bloomian Approach” (belief that ancient classics are the key, done with rigor), and the “Great Ideas Approach” (use of historical unit ideas—think Lovejoy—though, due to Kirk, being very selective on book written after after 1700 or so). – TL

Strauss had a bit of the cabalist in him. His master thesis, “Natural Right and History,” divides exactly to the page as a dialogue between “classic natural right” and “modern natural right.”

[The “classic” natural right half ends with Aquinas, albeit with protest.]

To the “Hillsdale” mind–the conservative mind–the dialogue is between the classical and modern, not dispensing with the Greeks, Stoics and Christian medievals as soon as decently possible so that we can get to the important stuff [Hegel and Marx and Dewey and Rawls and whatnot], but first understanding the classical so we can understand the grounds on which the modern project rejects it.

[Or doesn’t.]

However, I’m having enough trouble right now making myself read Bloom, Bennett, Kimball and D’Souza — the Four Horsemen of the Western Civ Apocalypse.

Demigods perhaps, but not really members of the conservative pantheon. Noam Chomsky might be the Bloom analogue, Chris Matthews the [Bill?] Bennett one, “Kimball” [Roger I suppose] moves the Conserv-o-meter even less than Bill Kristol, and poor Dinesh D’Souza is so completely out of the loop he makes Francis Fukuyama look positively relevant.

Not sure where you got this reading list, but “making yourself read” these people is masochism, not education. Perhaps whoever gave you this list is having a bit of fun with you.