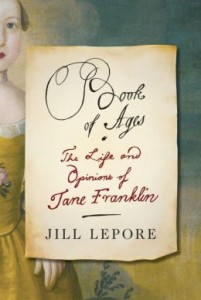

Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin

by Jill Lepore

464 pages. Knopf, 2013.

On April 16, 1722, Mrs. Silence Dogood, the literary invention of a frustrated 16 year old Benjamin Franklin long thwarted in his attempts to write for his brother’s newspaper, began her second letter to the New- England Courant

with a sharp statement on the writing of good biographies: “Histories of Lives are seldom entertaining, unless they contain something either admirable or exemplar.” Next, this fictitious widow and mother who claimed an impoverished childhood but lucky apprenticeship to a generous master willing to indulge her exceptional love of books, humbly added: “And since there is little or nothing of this Nature in my own Advetures, I will not tire your readers with tedious Particulars of no Consequence, but will briefly, and in as few Words as possible, relate the most material Occurences of my Life…” Notwithstanding such self-deprecation, young Ben Franklin’s Mrs. Dogood offered 18th century readers a confident, forceful voice critical of power and pride and full of democratic wit and words of common sense. Good thing Mrs. Dogood wasn’t silenced by an “ordinary” life seemingly undeserving of a biography. And for Jill Lepore, the Harvard historian and author of the powerful new biography about Ben Franklin’s little sister titled Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, Mrs. Dogood’s apology is a challenge to all historians who seek to write about the lives of people with “miserably scant” paper trails and silenced voices. Lepore’s work to excavate not simply the “material Occurences” of Jane Franklin Mecom’s biography but her intellectual life makes a case for the exemplariness and meaning of Jane’s life, no matter what Jane may have thought about herself. The boldness of Lepore’s project is its assertion that the unquestioned exemplariness and meaning of Benjamin Franklin’s life as brilliant Founding Father cannot be fully understood without Jane. That this argument is ultimately and wonderfully persuasive promises to land Book of Ages on every intellectual history graduate student’s reading list of “how to”s, but the sweat left on each page by Lepore’s evident effort and imaginative, speculative connections drawn well beyond the central couple will surely leave some readers still doubtful of the “Consequence” Book of Ages finds in Jane’s “Particulars.”

The heart of Book of Ages is the epistolary relationship between Benjamin Franklin and his youngest sister, Jane. Three years after running away from his apprenticeship and his parents’ home, Ben Franklin, age 21, wrote a letter to his 14 year old sister. Brother and sister would continue writing each other for the rest of their lives over a span of 63 years. That their relationship was cherished as important by each sibling is clear from the admiring and loving comments in the letters. For Lepore, these letters also provide a precious window into Jane’s thoughts. It is unlikely access to a woman like Jane: in contrast to her elder brother, Jane led a narrow life constrained by poverty and defined by her roles as wife and mother who gave birth to 12 children and helped take care of grandchildren and great grandchildren until she died in 1794 at the age of 83. Jane struggled to support her family financially, buried babies and grandbabies and deeply worried over one son with severe mental illness. It was not an unlikely life for an 18th

century woman without education or fortune or a husband who could find steady work. It was Benjamin Franklin who lived the extraordinary life: he left the home Jane never left and became, well, Benjamin Franklin.

Most of these letters no longer survive. Most importantly: no letter of Jane’s exists that was written before 1758 when she was 45. Jane did keep a handmade book which she entitled “Book of Age’s” (with an errant apostrophe) and recorded the birth and deaths of her children. For Lepore, such archival silence and the seemingly insurmountable obscurity of Jane’s life and voice was “dispiriting”: “For a long time, I was so discouraged that I abandoned the project altogether. I thought about writing a novel instead” (269). But the project she ultimately decided on writing “was a book meant not only as a life of Jane Franklin Mecom, but more, as a meditation on silence in the archives” (269).

So, how to write this story of a “quiet life of quiet sorrow and quieter beauty” (267)? How to write a life based on such a paucity of evidence? Lepore works hard and takes creative risks. Before 1758, she pulls the lens out wide to describe 18th century prescriptive literature about gender roles: “She was bred to bookery and cookery, needle and thread” (29). With no diary, memoir or letters of Jane as a girl, Lepore unearths Jane’s experience by describing the lives of others, and then adjusting the picture to fit Jane. For example, she lists the wide and vast selection of books that Jane Colman, the daughter of a Boston minister, read (a list available in the archives) before snapping the reader back to Jane Franklin: “What books (Jane Franklin) read were what books she found in the house of a poor soap boiler” (31). While there is no evidence of what books Jane actually read, Lepore paints a picture of a girl hungry to read based on lines Jane wrote to her brother much later in life–in a letter that has been preserved–documenting her desire to read all of his political writing. When describing Jane’s life as a young mother and wife, Lepore effectively imagines her life based on shreds of important yet scant evidence: her husband’s deep debt, her children’s births and deaths, and quite beautifully, the poetry of other colonial women . Lepore’s discussion of making Jane’s “silence” in these years “the object of my investigation than an obstacle to it” in the “Methods” section of the Appendix (269-270) will surely be an important, albeit polarizing staple in historiography seminars.

But no comparison does the work of drawing the obscure Jane Franklin into focus than that of Benjamin Franklin. Describing Franklin’s writing, reading and oratory skills even as a young man, documenting his travels away from home and underscoring his courage and self-confidence allows Lepore to write evocatively of Jane’s days “spent at home, close to the fire” (30). Here, weaving Benjamin and Jane’s stories allows her to show what Jane was doing by letting the well-documented details of Ben Franklin’s life show what Jane was not doing. When Ben Franklin leaves his apprenticeship, his older brother immediately puts out an ad looking for a “likely lad” as a replacement. Lepore’s pithy comment: “He had no use for a likely lass” (38). Here, Lepore snaps her readers back from the well-trod narrative of Franklin’s audacious trip to Philadelphia to consider the constraints on Jane due to her gender: the newspaper industry was closed to her. Wait, now, let the graduate seminar debate begin: but who ever said Jane wanted to be printer? And even if she did not have so much soap to boil and quilts to stitch, are we to think she would have rivaled Ben Franklin’s intellectual gifts? To diminish Franklin’s genius is not Lepore’s point. But her biography is not only a meditation on “silence in the archives” but a meditation on a life limited by gender roles. Lepore takes as her guide Virginia’s Woolf’s imaginative invention of Shakespeare’s equally talented but tragically doomed sister. Like many historians writing about women, Lepore dignifies Jane’s life by giving it depth and complexity too long denied while also lamenting its limitations. Lepore writes: “Whether a poet’s heart beat inside her woman’s body I leave it to the reader to decide, but sitting in that archive, holding these sheets of foolscap stitched together with the coarsest of threads, I began to think that Benjamin Franklin’s sister had something to say after all, something true, something new” (xiv).

What did Jane have to say? In the second half of the book while employing Jane’s actual written letters, Lepore clearly relishes the words—glorious words! glorious evidence!—of her subject. In her letters to Benjamin, Jane remains apologetic for her spelling and her intellectual “capacity” but she writes “full of opinions” (204). Most of these opinions concerned the domestic. As Ben Franklin spoke against the Crown in the years leading up to the Revolution, Jane documented her anger at British soldiers’ foul language and drunken attacks in her letters. Yet, she is also upset when colonial boycotts destroy her millinery business (she used fine cloth from England) and constantly writes Benjamin of her desire for peace: political unrest destroys her livelihood and forces her to flee Boston with thousands of others. But in a letter dated 10 years after the Revolution, Lepore identifies “the most revolutionary thought Jane Franklin Mecom had ever put down in writing” (218). Jane wrote to Benjamin about her reading of philosopher Richard Price’s Four Dissertations, citing Price’s assertion that genius had been “lost to the world, and loved and died in Ignorans and meanness, merely for want of being placed in favourable situations, and Injoying proper Advantages” (218). For Lepore, this demonstrates “a new spirit of equality” in Jane, furthered by Jane’s direct editorial comment to her brother: “Very few we know is Able to beat thro all the Impedements and Arive to an Grat Degre of superiority in Understanding” (218). She doesn’t list the “Impediments” she refers to but this isn’t necessary; Lepore has laid them all out in the pages that come before: the constraints of class and gender, even the unfortunate fall that renders a young boy lame. Here, finally is the crescendo of Lepore’s book: This commentary by Jane—proof of deep intellectual engagement with Price’s book– is the evidence Lepore had been waiting for when she first touched Jane’s “Book of Age’s” in the archive and felt that Jane had something “true to say.”

In her efforts to rescue Jane from Ben Franklin’s shadow, does Lepore speculate too much? There are many, many references to books Jane “may” have read and Jane’s story is emboldened with references to Jane Austen, Mary Wollstonecraft, Virginia Woolf, and Samuel Richardson, among many others. At times, a reader could be excused from thinking that Jane Franklin Mecom sat in intense conversation with these authors. Yet, such references give form to the desires of the writing, reading woman and Jane begins to emerge from the shadows.

Lepore asserts more than the “superiority of Understanding” of her subject. She argues that Jane Franklin Mecom is essential to understanding Benjamin Franklin. In a few places Lepore argues this most directly—she reconsiders the writing of Poor Richard’s Almanack in light of Franklin’s relationship with Jane and her two troubled sons, but in other places Lepore’s narrative simply positions Jane as present in Franklin’s life and mind when he is writing and working on affairs of State. This point, I think, will be the most contentious in grad school seminars. How much does she matter to understanding Benjamin Franklin? It is not clear what Franklin thought. The question Lepore writes to, yet never fully asks: Why didn’t he mention her in his Autobiography?

And it is this question, all the more poignant when it is clear how much her brother meant to Jane , that leads back to Lepore’s essential goal in Book of Ages: she offers an important demonstration on writing the history of obscure subjects and shows her reader clearly how and why she makes the choices she does as a writer. The tantalizing, yet frustrating scraps of Jane’s life suggested to her “a history of books and papers, a history of reading and writing…a history of history” (xiv) Until now, Jane has been erased from the historical record, not just in Franklin’s Autobiography but by the historical biographies that followed. How do you unearth such an obscure subject? What methods do you use? Why do you bother? Towards the end of Book of Ages, Lepore asks: “What would it mean to write the history of an age not only from what has been saved but also from what has been lost? “ (242). This is precisely what she has done with great skill and illumination.

Mary Ellen Lennon is an assistant professor of history at Marian University in Indianapolis. Her present project examines the Harlan County Coal Mining Strike of the 1930s.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This interesting review perhaps tends to mix together the problem of obscurity with the problem of a small or partial paper trail (“silence in the archives”).

Shakespeare is the opposite of obscure, but there is relatively little documentation of his life (there are the plays and poems, of course, but I’m talking about factual documentation: there’s no diary, no letters (iirc), basically just some business records, the announcement of his marriage, his will, and a few references to him by others). So every biographer of Shakespeare has to speculate to some extent. If Lepore’s colleague S. Greenblatt could speculate about Shakespeare in Will in the World, why can’t Lepore speculate about Jane Franklin? The problem, it seems to me, is not so much the need to speculate as the underlying motivation or justification.

No particular justification is needed for speculating about why Shakespeare moved to London when he did, since most of what Shakespeare did is presumptively important because he’s Shakespeare. Whereas when Lepore speculates about what books Jane Franklin might have read, the question is why one should care. Which is presumably why Lepore has to argue that you can’t understand Benjamin Franklin without understanding his sister. Her historical importance derives from the fact that she is his sister. Otherwise, if one wanted to write about an obscure 18th-cent. woman, one would probably pick one who had left more of a paper trail covering her whole life (as opposed to a paper trail only from age 45 on).

It’s probably a moving book, esp. in underlining the “impediments” of gender and poverty. I’m only suggesting that the root of the issue here is the subject herself, or the choice of subject. The review’s suggestion that the book will spark debates, at least among students, is no doubt right.

Love the review, Mary Ellen. Thanks for going over this book and bringing to my/our attention. – TL