The following post is from Donna J. Drucker, a guest professor at the Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany and the author of The Machines of Sex Research: Technology and the Politics of Identity, 1945-1985 (Springer, 2014). She is at work on a book on Alfred Kinsey that will appear in the fall of 2014.

The following post is from Donna J. Drucker, a guest professor at the Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany and the author of The Machines of Sex Research: Technology and the Politics of Identity, 1945-1985 (Springer, 2014). She is at work on a book on Alfred Kinsey that will appear in the fall of 2014.

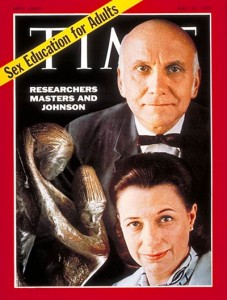

Masters of Sex is a new, heavily promoted Showtime program that depicts the working relationship between the sex researchers William H. Masters and Virginia E. Johnson. The program is based on a dual biography of the same name by the journalist Thomas Maier (listed in the program credits as a producer) that focuses on their personal relationships, but also sets up the series to take their science at least somewhat seriously. The characterizations of Masters and Johnson, however, and the depictions of their personalities and motivations, may get in the way of illustrating the realities of who they were and what they achieved.

The pilot episode of the show introduces the viewer to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Washington University in St. Louis in October 1956. The costume, set, music, and props staff did an excellent job of making the scenes look authentic to the period. Masters hires Johnson as a special assistant on a sex research project after discovering that she has been sexually adventurous with one of his junior colleagues, firing the heavier, older, bespectacled female secretary who does not seem to have the right erotic life for the job. The pilot moves quickly through the first few months of Masters and Johnson’s collaboration, in which they (with the help of unseen technicians) develop a penis-camera, decide to measure sexual physiology both with singles and couples, recruit volunteers from among the hospital staff, and argue with the provost over political and financial support for the project. By the end of the pilot, Johnson has begun to wear a doctor’s white coat despite her lack of a professional degree or medical training, and she is already explaining the four-stage sexual response cycle (arousal, plateau, orgasm and resolution) to the white, slender, conventionally attractive couple who is the project’s first paired set of subjects. Lastly, Masters and Johnson’s project develops an added level of tension after he proposes that he and she become one of the paired sets of subjects together.

The show falters historically in how it sets up the motivations of Masters and Johnson themselves, and Johnson’s characterization is particularly problematic. It is unclear from the pilot that one of the main problems that Masters was trying to solve in his research was not discovering the secret key to women’s sexuality generally, but rather the relationship of sexual behavior to fertility. The show depicts Masters as a cool, unflappable man of science, driven to excel and desirous of challenging university authorities in order to be a pathbreaker in the field of sexual physiology. Masters was clearly more devoted to his work than to his first wife, and their marriage faltered as a result. It is quite another leap of imagination to suggest, as the script does, that Masters was a terrible lover, and that his desire to solve the mysteries of female sexuality in general comes from his own personal problems with marital intimacy.

The show falters historically in how it sets up the motivations of Masters and Johnson themselves, and Johnson’s characterization is particularly problematic. It is unclear from the pilot that one of the main problems that Masters was trying to solve in his research was not discovering the secret key to women’s sexuality generally, but rather the relationship of sexual behavior to fertility. The show depicts Masters as a cool, unflappable man of science, driven to excel and desirous of challenging university authorities in order to be a pathbreaker in the field of sexual physiology. Masters was clearly more devoted to his work than to his first wife, and their marriage faltered as a result. It is quite another leap of imagination to suggest, as the script does, that Masters was a terrible lover, and that his desire to solve the mysteries of female sexuality in general comes from his own personal problems with marital intimacy.

Johnson, who was thirty-one when she first met Masters, is shown as a self-confident woman, unafraid to demand erotic satisfaction in bed from a male partner, but astonished when he cannot understand that she wants only physical, not emotional intimacy. In her job interview with Masters, she states that “women often confuse love with physical attraction…women often think that sex and love are the same thing.” Such ideas of second-wave female sexual empowerment inflect much of her dialogue, making her sound much more 2013 (or even 1970) than 1956, which is a clear mischaracterization of her approach to human sexuality. Johnson intended her and Masters’ research to support heterosexual marriages, as she derided “lady liberationists” who intimidated men in bed (David Allyn, Make Love Not War, 1996). The liberatory potential in Human Sexual Response (1966) for the sexuality of women was the result of later feminist scholarship , not her own proto-feminist sensibilities (Jane Gerhard, Desiring Revolution,

2001).

As the author of two books on the history of sexuality (The Machines of Sex Research, 2014, and The Classification of Sex, forthcoming 2014), I have devoted a lot of my own intellectual time thinking about the motivations of sex researchers for doing their work. In many previous writings on Alfred C. Kinsey, for example, biographers and critics ascribe his motivation for a professional career in sex research to his strict Methodist upbringing, virginity until marriage, difficult wedding night, or other psychological reasons. Kinsey never himself described why he made the move from gall wasps to human sexuality, but there is much clearer historical evidence that he made such a move to forward his professional career and research profile rather than to resolve old psychological problems.

Masters of Sex runs a similar risk of making thinly supported speculations about Masters and Johnson’s psychologies its subject, rather than the genuinely intriguing twists and turns in the historical records of their sexual science, their shift to marital therapy in the 1970s, and their later mismanagement of their finances and misguided research on homosexuality. Masters divorced his long-suffering wife Libby in 1971 and married Johnson, but they too divorced in 1992 after Masters reunited with his high school sweetheart while enduring the early stages of dementia. Contemplating why people do what they do, especially when they live such interesting lives and leave behind so little historical evidence of their reasoning, can be fascinating. Doing so can make compelling movies and television, but it does not always make for good history.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I enjoyed reading this piece, it served as a reminder of the dangers of over-reading, how we bring our own baggage to excessive interpretations and end up misreading our object of study. Freud practiced this form of “hermeneutic excess” himself, as one can attest in his obsessive fixation with Dora and other analysands (btw, the quote “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar” is wrongly attributed to him; a myth that circulate to this day).

But these misreadings can also be productive (see Derrida as a master of productive misreadings), and can sometimes illuminate cultural and political paradoxes. This show reads more in terms of a certain heteronormative tradition of cultural representations of gender and sexuality in the US, with particular gendered types, and so forth, than anything else.