Memory

September 11, 2001 began, for me, with vague news about a “plane accident” involving the World Trade Center. This is all my Chicago NPR station gave me before leaving for work. At that point it wasn’t about a large jet, commandeered by terrorists, being used as a bomb to destroy a major symbol of American prosperity and strength in the heart of its biggest city. It was just an unusual incident. Details were scarce.

Everything changed in about 30-40 minutes. After arriving at work the purported accident had transformed into a major catastrophe. There were only a few of us in the office, but our individual browsers were filled with images of horror and dread. One of my colleagues wheeled out a television, and we began to watch events unfold together. It reminded me of a January afternoon in my high school freshman English class. After the space shuttle Challenger disaster, our teacher, Ms. Thomas, had us watch the coverage and discuss the events.[1] In 2001, it was my Loyola colleagues and I, with no guidance, feeling our way through another televised disaster in the sky. I was a part-time graduate assistant learning to advise students at Loyola’s adult education outpost, Mundelein College. Thankfully business was light that day.

Everything changed in about 30-40 minutes. After arriving at work the purported accident had transformed into a major catastrophe. There were only a few of us in the office, but our individual browsers were filled with images of horror and dread. One of my colleagues wheeled out a television, and we began to watch events unfold together. It reminded me of a January afternoon in my high school freshman English class. After the space shuttle Challenger disaster, our teacher, Ms. Thomas, had us watch the coverage and discuss the events.[1] In 2001, it was my Loyola colleagues and I, with no guidance, feeling our way through another televised disaster in the sky. I was a part-time graduate assistant learning to advise students at Loyola’s adult education outpost, Mundelein College. Thankfully business was light that day.

With everyone else I was of course shocked at the start. But as things progressed—as the towers fell, people died, and speculation rolled in—a numbness overcame me, followed by helplessness, hurt, anger, and fear. Then the questions: Who did this? Why? What was going to happen to Chicago? Was my girlfriend safe? What about my family?

History

Although I was well into training for my new, hoped-for career as a historian by September 2001, and I was learning a lot fascinating cultural history, I still didn’t instinctively look to history for answers to what I was seeing. For one, I was just trying to absorb the scope and possibilities for the present and future. Plus, at that point my historical thinking was still developing and compartmentalized. I hadn’t developed much breadth. I was more of a philosophical-theological thinker who sought out ethical and moral roots. When I thought about history in the wake of 9/11, it was more about the present state of terrorism, religion, and war in general. I simply wasn’t interested in the history of foreign policy, political history, and the history of the Middle East. It says something about my historical thinking in those areas that Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” thesis seemed to have a lot of merit, even if imperfect in every application.

Like many others at the time I was satisfied with President George W. Bush’s response to 9/11. This sense of satisfaction went on for several months—for almost two years actually. I’m sure my relative contentment was driven by the fact that I had voted for Bush.  Perhaps I wanted to protect my choice, and his subsequent choices, from those who felt he had been elected illegitimately, as well as from my own increasing uneasiness with his policies (e.g. the Bush tax cuts). I didn’t want the invasion of Iraq, but I wasn’t opposed. I felt (again, with many others) that Colin Powell had made a forthright and compelling case for war (at the U.N. furthermore—who would purposely deceive so many important people on such a stage?). I trusted not only Powell, but what seemed, then, like overwhelming American intelligence. We weren’t an imperial power imposing our will on the region, but a nation protecting its homeland, as well as its political and trade interests.

Perhaps I wanted to protect my choice, and his subsequent choices, from those who felt he had been elected illegitimately, as well as from my own increasing uneasiness with his policies (e.g. the Bush tax cuts). I didn’t want the invasion of Iraq, but I wasn’t opposed. I felt (again, with many others) that Colin Powell had made a forthright and compelling case for war (at the U.N. furthermore—who would purposely deceive so many important people on such a stage?). I trusted not only Powell, but what seemed, then, like overwhelming American intelligence. We weren’t an imperial power imposing our will on the region, but a nation protecting its homeland, as well as its political and trade interests.

At this point, around the summer of 2003, I believed that, however undesirable, the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq were necessary. Although the Bush Doctrine of preemptive strike and preventive war was out there, it wasn’t widely publicized, I think, until its update in 2006. As of 2003 it seemed, to me, that the administration was all about hunting down and rooting out Al Qaeda, as well as taking away Saddam Hussein’s ability to use weapons of mass destruction. I was all in, as they say, for both.

Apart from feelings about the post-9/11 political scene, my explorations of the great books idea and Adler (as well as teaching, a trip to Ireland, and an engagement) kept me plenty busy. The Adler work either kept my historical thinking focused, or naively compartmentalized. I could use the “Nine Cs” in relation to Adler and the great books, but I wasn’t yet confident enough to apply my new mode of thinking for recent history outside my specialty. And, again, I wasn’t (yet) consciously seeking the best historical thinking about foreign affairs.

Despite being “all in” as of February of 2003, it didn’t take long for doubts to arise. The passions that start a war can’t be sustained forever. This is especially true when a war was begun on shaky grounds and deception. In the summer of 2003 it was becoming clear that the evidence for WMDs either wasn’t there or was skillfully hidden. Hussein was hiding. Though he would be found later that summer, the outrage that was Abu Ghraib was reported early in 2004. There were the regular images from Guantanamo Bay. The civilian casualty numbers in Iraq and Afghanistan were never clearly given, but stories of civilian deaths were leaked. And Al Qaeda wasn’t in Iraq. Either they were never there, or they had left when it became clear the United States was coming. By early 2004 it was exceedingly clear that America wasn’t seen by the Iraqis as the liberator, as President Bush had promised. Hussein had been a brutal dictator, but we were now the enemy. Given these events, I was unable to answer objections raised by my friends to our involvement in Iraq. I was war weary, if not precisely war wary.

Meaning

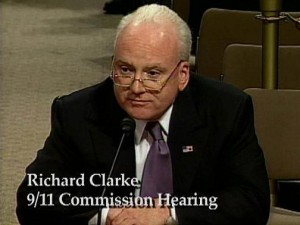

My feelings about the situation reached a breaking point in June of 2004. That’s when my girlfriend-become-spouse and I happened to be in front of television for a random viewing of 60 Minutes

. I was ripe for some kind of conversion, and Richard Clarke caused the scales to fall from my eyes.[2] Though that metaphor makes it seem like an act of God, or magic. It was really just a proverbial “a ha” moment. A very convincing Clarke outlined Bush’s and the Bush team’s insistence on linking Hussein to 9/11. He spoke of the administration’s willingness to select its evidence and twist public opinion. Clarke seemed so genuine and concerned, and his details were so overwhelming, that even if you didn’t believe him completely, you had to take him seriously. He would later be interviewed by the 9/11 Commission. But the 60 Minutes interview was the turning point for me. Clarke gave a focus and energy—a whole new meaning—to my conscious and unconscious doubts about our country’s long-running reactions to 9/11.

I became a permanent skeptic of all things Bush after June 2004. I had been leaning against voting again for him again, but Clarke sealed it. I wrote-in a presidential candidate that November, and I haven’t voted for a Republican candidate in any election since—not at the federal, state, nor municipal level. Not only did Bush squander our post-9/11 national solidarity, but his legacy on security, both at home and abroad (this story too), is now squarely negative, or decidedly mixed at best. It wasn’t difficult to feel pretty justified in my newfound skepticism of all things Bush.

Because of the Bush administration’s post-9/11 actions, my view of those events from 2001 are more ambiguous than ever. I’m still moved for the lives lost and ruined that day in New York City. I’m no less a patriot in that the injustice of the attacks still touches a deep nerve. I’m continually unhappy with the fact that soldiers’ lives are still being lost. But as much, and sometimes more, I’m also moved by the great many innocent civilians lives lost in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Just yesterday I watched a moving tribute on ESPN titled “Man In The Red Banana.” Despite the corny title, this short video story traces the life a young man, Welles Crowther, who died in the South Tower of the World Trade Center. More accurately, this young man sacrificed his life for others, saving the lives of several injured workmates on the upper floors of the building. He ushered them down, and he went back up for more. He died when the building collapsed.

The video was moving and meaningful for me. But I also immediately thought of all the Iraqi civilians that have died in what now seems like a wasted war. The country is now basically yet another American enemy, and civil strife is still prevalent. For every Welles Crowther in America, there are probably 10 Iraqis who see America as the cause of a lost future. We killed their mother, brother, aunt, or sister, and all for flawed premises—or worse. We killed the person who might’ve changed that family’s or that country’s future. When I think about 9/11, I now empathize as much with those who, at the time, were thought to be our enemy. This is the Bush legacy for me. And it is now connected to the meaning, the legacy, of 9/11.

The video was moving and meaningful for me. But I also immediately thought of all the Iraqi civilians that have died in what now seems like a wasted war. The country is now basically yet another American enemy, and civil strife is still prevalent. For every Welles Crowther in America, there are probably 10 Iraqis who see America as the cause of a lost future. We killed their mother, brother, aunt, or sister, and all for flawed premises—or worse. We killed the person who might’ve changed that family’s or that country’s future. When I think about 9/11, I now empathize as much with those who, at the time, were thought to be our enemy. This is the Bush legacy for me. And it is now connected to the meaning, the legacy, of 9/11.

I should add that this intensification of skepticism fed both a new, more detailed interest in domestic and foreign politics, as well as political history generally. The actions of the Bush administration after 9/11 turned me into a more careful student of political history. Like others I still react superficially to political news. Those who follow my Facebook posts know this. But there’s the realm of reaction and the realm of reflection. On the latter, I try harder than ever to consider all the elements of historical thinking when I seriously attack a political issue (e.g. sources, causes, complexity, change over time, contingency, and context). I prioritize historical and practical factors over moral and philosophical considerations. The latter two still matter a great deal; they just don’t rule my serious political engagements.

So my memories of 9/11 are tangled up with two wars, public deceptions, a huge personal political conversion, and an intensification of my historical thinking while going from graduate student to history professional. While the events of 9/11 remain relatively clear to me, the legacy of 9/11 is something entirely different. No one will ever again receive an “all in” pass when war is involved, no matter how shocking the catalytic event.

————————————-

Notes

[1] Apparently that day was also memorable for Ms. Thomas, as she found herself reflecting on it again earlier this year.

[2] More on that interview and Clarke’s book are available here.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Tim, I think what I like best about this post is how it captures the texture of that day for those of us who were watching the awfulness from afar — the confused jumble of reports and conjectures, the growing sense of sorrow and anger and fear, the need to be with others on that day, to go through the day together.

I did not so much as mention 9/11 to my students yesterday. I just couldn’t. But I was lecturing on the new immigrants of the Gilded Age, so I started by reading “The New Colossus” and the led the class through an analysis of the poem. Of all the kinds of texts we can deal with as intellectual historians, poetry — broadly construed — is the hardest for me to handle. It works on me, it works through me, and it’s very difficult to step out of that stream of sound and sense and soul and discuss a poem as a piece of historical evidence.

Not all poems are like that for me. But on 9/11, that poem certainly is. I was a little worried yesterday that there would be a bit of a tremor in my voice when I read it. But the ethical obligation that comes with teaching, that sense of solemn duty to exemplify clarity and calm in the face of confusion, was a welcome burden that — to my pleasant surprise — weighed me down like an anchor.

I would be curious to know whether / how history instructors addressed the anniversary in their teaching yesterday, especially if they are looking at something other than very recent U.S. history.

Thanks for the comment, LD.

I don’t know how other history instructors would’ve handled 9/11 on day slated for different topics. But, depending on my sense of the class and the mood of the day, I may have asked the class if they wanted to discuss it. If they decline, then I move onto the formal agenda. If yes, then I’d probably start with questions for them (and I’d post/track answers, via keywords, on the board): What do they know about 9/11? How old were they? What does 9/11 mean to them? What would they look for in any historical narrative of it? The last would be where I reinforce the elements of historical thinking. – TL

This is a slightly different take, but I remember being a TA last fall and my prof talking to our students about 9/11.

It was jarring to realize that the students in college we’re talking to now about 9/11 were children when it happened. As it was, my prof and I both told them our experiences, she being in grad school and I being in high school.

I really like this post Tim. It brought back all kinds of memories of 9/11 for me. It was a teaching day (unlike 9/11/13, to answer LD’s what-did-you-tell-your-students-yesterday question with a kind of non-answer). Like you, I heard NPR reports of a plane hitting a tower on my drive in. Like you, I assumed it was an accident involving a small plane. I went to my office to prep for class. And sometime shortly afterward a colleague told me what was going on. I spent the rest of the morning glued to the TV in the Honors College student lounge. I may have tried to start my early class, but we went back into the lounge and watched events unfold. Then classes were cancelled. I felt numb for weeks. I ended up skipping the ASA Meeting in Washington, DC. With anthrax and (I think) snipers, the nation’s capital just didn’t feel safe. Everything felt like a mess. Unlike you, I didn’t vote for Bush in 2000 and had absolutely no illusions about him. Nevertheless, I tried to find hope in his response. I convinced myself that, under the circumstances, he did ok, or at least not as badly as I had feared. I supported — or at least didn’t oppose — the War in Afghanistan. But by the time the Iraq drums were beating I had begun to fully realize what a disastrous combination of circumstances and leadership this country had found itself in. I have other feelings and memories around 9/11 at the time and today, but I haven’t digested them enough to share at the moment. Thanks, again, for the post!

Thanks Ben. I had forgotten about the anthrax mess.

Contingent history thought: I wonder how much more intense our reaction to Pearl Harbor would’ve been if it had been covered on television? Or I wonder much more opposition to nuclear weapons there would be if we had televised coverage of aftermath in Hiroshima and Nagasaki? …Per Claire Potter’s recent Tenured Radical post, my opposition to napalm has been catalyzed by images (moving and static) from the Vietnam war. – TL