“What is the morality of doing nothing?” barked President George H.W. Bush.

“What is the morality of doing nothing?” barked President George H.W. Bush.

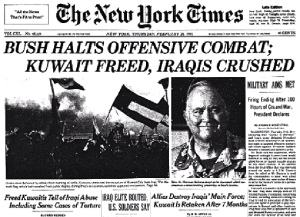

The president had been pressed by one of his spiritual advisors the presiding bishop of the American Episcopal Church Edmond Browning, to defend the build up and obvious intention to use military force against Saddam Hussein. In the days leading up to the bombing campaign against Bagdad and Hussein’s forces in Kuwait, Bush had consulted advisors, political, diplomatic, and spiritual. Why spiritual? I grappled with that question in God and War

, arguing that Bush thought religion mattered.

Michael Barone noted that the president sought the advice of “at least four religious leaders” including perennial presidential favorite Billy Graham. According to Bush confidants, the president and first lady prayed nightly and “aloud for the safety of the American forces and for quick, decisive U.S. victory in the gulf.” Significantly, though, Bush believed he had right on his side—he followed his own “just-war” doctrine. “Those familiar with the president’s thinking say that he hews to the classical doctrine of a ‘just war’ based on a belief that deadly force is sometimes a tragic, but moral, necessity.” Bush combined a view of providential design and unipolarity to create a moral vision. He claimed to be born again, at least by the 1988 campaign, and to believe that God’s will was not a complete mystery; for instance, he thought there was a reason his life had been spared during World War II. Bush grew downright righteous when he read reports of Iraqi atrocities in Kuwait. In his exchange with Browning, Bush’s indignation boiled over: listening to his pastor argue that Saddam should be given more time, the president pointedly asked Browning whether he had read the Amnesty International report on the occupation of Kuwait. America had to do something, Bush demanded, for it was the “only nation strong enough to stand up to evil.”

Browning and many other religious leaders in 1991 remained unconvinced. As were many in Congress at the time. New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan had registered his profound displeasure with Bush’s unilateral build-up of American military forces in the Gulf before asking Congress for its support or defending his decision to the American public. When a group of Senators sent the president a letter asking for clarification of why those forces had clearly shifted to a posture of offense, they made clear that while “the Congress and the nation stand behind our troops in the Gulf,” they also contended that “in face of the troop buildup, the President owes the people of the nation a clear description of our goals in the region, the potential costs of achieving those goals, and the purposes we intend to achieve there.”

Of course lurking behind Bush’s decision to launch attacks against Iraqi forces was the specter of Vietnam. The Vietnam Syndrome–an unfortunate name for the will to be cautious about starting a war–had clearly infected Bush. In an address to the nation on November 22, 1990, Bush took care to describe American intentions in almost humanitarian terms: he understood that Kuwait was not a democracy and that liberation of Kuwait from the Iraqis would not mean freedom for all the people of Kuwait. And while Bush purposefully employed the Munich analogy to make his case in the Gulf, he also knew that he could not avoid the Vietnam analogy. “In our country, I know that there are fears about another Vietnam,” he said. “Let me assure you, should military action be required, this will not be another Vietnam. This will not be a protracted, drawn-out war.” He promised “not to permit our troops to have their hands tied behind their backs.” And he pledged, “There will not be any murky ending.” At the end of the president’s prepared remarks, he made an appeal to Saddam to enter into discussions leading to Iraq’s unconditional exit from Kuwait. Yet after Bush’s presentation of an argument that made the crisis sound like a choice between freedom and appeasement, it grew increasingly difficult to imagine how the United States would not go to war.

We have once again arrived a similar moment–though obviously not exactly the same. And as we watch this latest crisis unfold, I am interested in how we consider and debate American actions in light of the recent past–in Iraq and Afghanistan–a more distant past–Vietnam and it’s “syndrome”–and the idyllic past–the wars that have become righteous in the nation’s mythology. The legal scholar and novelist Stephen Carter wrote a book on just war and teaches a very popular seminar on it at Yale. He makes the point to his students that there are basically a small number of nations that can deliver military power with any precision and skill around the world. The United States stands at the very top of that list. With that ability comes, as President Obama has demonstrated, the necessity to draw “red lines” and hold other nation’s accountability for certain atrocities. The president has suggested that this capability defines the nation as much as the ceremonies just concluded at the Lincoln Memorial in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement. As we continue to bask in the heroic moral authority of King, how should we evaluate the deployment of American moral authority in war? In short, how does the American public draw its red lines?

13 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Continuing a discussion theme that has begun under yesterday’s post, I feel qualified to comment on this in only two ways: first, as a generalist that considers the elements of historical thinking in any situation; second, as someone who has studied the domestic consequences of overseas wars.

On the first, I’m not sure that red lines in the Middle Eastern sand appropriately account for the context (recent wars, religious diversity), complexity (again, religious diversity, but also internal and interventionist politics ), characters (Assad as a dictator, diversity of rebel groups), and causes of change in the situation (e.g. using war rather than discourse to promote peace).

On the second, Americans seem tired of playing the role of world’s policeman in an environment (however artificial and constructed) of “limited resources.” And the Vietnam Syndrome is under control, sort of, inasmuch as people don’t seem to compare Iraq and Afghanistan to Vietnam. But it’s clear those are protracted, draining, drawn-out wars of necessity and choice. Also, what of the dynamic of presidential actions versus actions that have the full faith and backing of the entire U.S. government via a Constitutionally-mandated Declaration of War? That question hasn’t been properly addressed since the “Korean Police Action.”

So, there’s a great deal of legit questions to be asked by those who know NOT A SINGLE THING about Syria’s history (other than ancient history I learned in the Bible). – TL

One more thing on my first point about solid historical thinking: sources. Are you 100 percent sure of our intelligence? Do we really KNOW what we think we know—especially since France and England are players but are not backing us unequivocally? – TL

And contingency: Have we properly mapped out (i.e. gamed) the potential contingent actions by neighboring rogue groups and nations? Are we prepared for all of those contingencies? ….Sigh.

I’m not clear what moral action is being proposed. I suppose ostensibly it’s to stop the Syrian regime from using chemical weapons but do we know that they have used them or that the rebels aren’t also culpable? If we do intervene is it for purely moral reasons, I think not. As Carter interprets Holmes, “In other words, no matter how passionately we may speak of the value of life at home, we rarely mean it abroad. The sacredness of life stops at the water’s edge.” Whose/what intentions will we be serving, Israel, Saudi Arabia, American economic etc.? I think the moral question hinges on the political one, in which case it’s no longer a moral question.

No, action taken by a nation cannot be seen in pure moral terms. But action that leads to death would have a moral dimension, I think. So how do you parse the political from moral or are they intertwined?

Oops! Response on #4.

Here’s an answer to my question about sources. Notice I said “an” and not “the.” I don’t know exactly what to do about it, but it ~looks~ rather convincing.

You’re right to challenge that statement, of course it is a moral decision too. I think (maybe cynically) the moral dose that goes into the chemistry of decision making gets diluted by political purposes.

I’m still back at

Bush barked? Who is the source on this? He seems more a cat person.

It’s de rigueur in certain circles to drag in the Bushes whenever it comes to evaluating the Obama presidency. So be it. Bottom line is that the Bushes had congressional authorization for their actions. If we made a mistake, we as a nation made it together.

http://firstread.nbcnews.com/_news/2013/08/30/20256971-nbc-poll-nearly-80-percent-want-congressional-approval-on-syria?lite

I guess I’m hung up on the notion of an “American public.” When it comes to popular involvement in foreign policy in particular, Lippmann is still right that it’s a “phantom”–in reality, “public” means “organized interests.” Following the Iraq war in 2003, the Council on Foreign Relations renewed its interest in “public diplomacy.”

http://www.cfr.org/diplomacy-and-statecraft/public-diplomacy-strategy-reform/p4697

Has any progress been made on this front?

Mark, you asked the question that both stumps anybody trying to write about these situations, but also allows leaders to speak in broad generalizations. So, yes, there is no unified public and yet we do expect some kind of debate that might be called public. Your invocation of Lippmann is right on, but have a streak of Randolph Bourne’s skeptical optimism as well–the more we name or at least speak openly about a situation with serious moral and political consequences the more we might get at the democratic culture we’d like to operate within.

Agreed on the skeptical optimism front. Just spent two weeks researching the CFR’s Foreign Relations Committees (1938-52) as an effort to do foreign policy from the “bottom-up.” More to be said on this at UC Irvine.

On most issues, the American consensus hasn’t been all that hard to discern.

We were for the Korean War but also for Ike ending it.

The polls turned against Vietnam as early as 1967 yet gave Nixon consistent approval through 1973 on how he was handling winding down the war.

Gulf War I got congressional support from all the GOP and half the Dems.

The Senate approved Bill Clinton’s Kosovo move, and although Tom Delay rigged a tie vote in the House [joined by 26 Dems], Clinton had enough of a go-ahead to claim legitimacy.

Gulf War II had all the GOP and half the Dems,and despite revisionist claims that the Authorization for use of military force wasn’t a green light to get Saddam, it was.*

And although Barack Obama had no authorization from Congress on Libya, neither did the GOP as a party make more than token objections to the operation.

Etc. IMO, at least on the big things–right or wrong– we have usually avoided bald majoritarianism in favor of consensus.

____________________

*http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ243/html/PLAW-107publ243.htm