Over at First Things, editor-in-chief R.R. Reno (right) attempts to take stock of American Catholic conservatism (or orthodoxy) from the beginning of the Culture Wars to the Summer of 2013 and beyond. I found the piece more fascinating for its view of recent American history than its future speculations.

Over at First Things, editor-in-chief R.R. Reno (right) attempts to take stock of American Catholic conservatism (or orthodoxy) from the beginning of the Culture Wars to the Summer of 2013 and beyond. I found the piece more fascinating for its view of recent American history than its future speculations.

Most prominently, I was struck by Reno’s acknowledgment of the importance of “second things” (my term) like context, change over time, contingency, complexity, etc.—historical thinking, in a word—even while exhibiting clear weaknesses in that latter category of thought.

Here are some excerpts from, and my critical replies on, the “First Things School of History”:

(a) In the 1980s and 1990s, theological liberalism seemed a powerful, or at least recently powerful, force. First Things consistently fought against its influence. The journal accepted modernity and argued that the achievements of modernity—democracy, respect for the dignity of the human person, the central role of freedom—are an integral part of the Christian message and sustained and renewed by loyalty to religious authority. We rarely let pass an opportunity to criticize theological liberals and point out the decline of mainline Protestantism. Today theological liberalism is no longer a force in the churches. We have in that sense won, and won decisively.  In the Catholic Church, most theological liberals argue for their right to exist rather than assume they will determine the future direction of Christianity.

In the Catholic Church, most theological liberals argue for their right to exist rather than assume they will determine the future direction of Christianity.

ME: “The journal accepted modernity”? Did this include the full acceptance of scientific findings, of individual expression and development, of changed women’s roles, of pluralism? And over what period of time did Catholic “theological liberals…assume they [would] determine the future direction of Christianity”? From 1955-1965? During Vatican II and for a few years after?

(b) When First Things was founded, Richard John Neuhaus could presume a broad range of religiously engaged people who had diverse political commitments. The journal’s inaugural editorial announced: “If the American experiment in representative democracy is not in conversation with biblical religion, it is not in conversation with what the overwhelming majority of Americans profess to believe is the source of morality. To the extent that our public discourse is perceived as indifferent or hostile to the language of Jerusalem, our social and political order faces an ever-deepening crisis of legitimacy.” We saw ourselves speaking on behalf of the majority and against a narrow secular elite. This is no longer true.

ME: So, in 1990 and the 1990s, “Neuhaus could presume a broad range of religiously engaged people who had diverse political commitments”? Considering that the journal began in the heat of the Culture Wars in the U.S., and those “wars”—in the eyes of one prominent authoritative observer—pitted the orthodox against the progressive, with the former being conservative and Republican and the latter being liberal and Democrats, how was that presumption possible? Given that environment, did Neuhaus really presume First Things-style orthodoxy was to be found with progressive Democrats? Was that environment truly “hostile to the language of Jerusalem,” or was that language simply being debated—with the journal joining to push the debate in a particular direction?

ME: So, in 1990 and the 1990s, “Neuhaus could presume a broad range of religiously engaged people who had diverse political commitments”? Considering that the journal began in the heat of the Culture Wars in the U.S., and those “wars”—in the eyes of one prominent authoritative observer—pitted the orthodox against the progressive, with the former being conservative and Republican and the latter being liberal and Democrats, how was that presumption possible? Given that environment, did Neuhaus really presume First Things-style orthodoxy was to be found with progressive Democrats? Was that environment truly “hostile to the language of Jerusalem,” or was that language simply being debated—with the journal joining to push the debate in a particular direction?

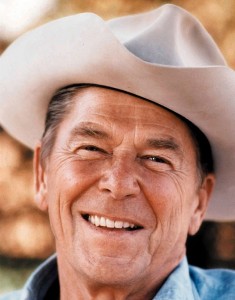

(c) First Things is associated with an optimistic phase of American conservatism. The Reagan coalition affirmed American exceptionalism, sought to unleash the creative potential of capitalism, and was influenced by a can-do, problem-solving neoconservatism. The Reagan coalition has run its course. Today, American conservatism is often angry or despondent rather than optimistic. A McCarthyite mentality has emerged that insists the progressive tradition is alien and un-American.  A hard-hearted libertarianism is replacing the warmth of Reagan-era patriotism and its affirmations of national solidarity. An apocalyptic mentality (national bankruptcy, demographic decline) promotes policies less as opportunities for renewal than as bitter necessities that follow from this or that collapse. More broadly, as the Reagan coalition has unraveled, the Republican party has become undisciplined and its political culture exotic, often to the point of embarrassment.

A hard-hearted libertarianism is replacing the warmth of Reagan-era patriotism and its affirmations of national solidarity. An apocalyptic mentality (national bankruptcy, demographic decline) promotes policies less as opportunities for renewal than as bitter necessities that follow from this or that collapse. More broadly, as the Reagan coalition has unraveled, the Republican party has become undisciplined and its political culture exotic, often to the point of embarrassment.

ME: Wait, if I’ve read my George Nash correctly, it was 1960s libertarianism, via Milton Friedman, that was the policy-oriented and problem-solving branch of post-WWII conservatism. So when, precisely, did libertarianism grow “hard-hearted”? Isn’t there an intellectual ideological strain of neoconservatism that accompanied the “Reagan Revolution” and its political descendants? I understand the rhetorical optimism of the Reagan era, but how were its policies practically “optimistic”—if we can define optimism as something distinct from unrealistic, guesswork, or ideological? And wasn’t an apocalyptic rhetoric a part of the New Right and the early, first-term Reagan oeuvre (e.g. heating up the Cold War, fear of end of America and its values—fear enough to inspire art like this)?

Perhaps if First Things-style historical conservatism was more reflective about “Second Things,” it would would be able to acknowledge some of its essential relativism. – TL

———————————————————-

Aside: I hope to finish up my look at Michael Kramer’s Republic of Rock next week.

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Reno writes “The journal accepted modernity and argued that the achievements of modernity—democracy, respect for the dignity of the human person, the central role of freedom—are an integral part of the Christian message and sustained and renewed by loyalty to religious authority.”

Question: if you can claim that democracy and freedom are integral parts of the Christian message, what will prevent you from asserting that racism and authoritarianism are integral parts of the Christian message when it becomes politically useful to do so? I think a Jesuitical ethic of dissimulation is at work here. You can surely argue that Catholicism is right if you like, but isn’t it just silly to claim that it ever was or every could be democratic without ceasing to be itself or at least straying very far indeed from orthodoxy in the manner of Gary Wills?

As is always the case in relation to innovations (institutional, political, social, educational, etc.), the Catholic Church decides to consider, support, or deny the potential change based, theoretically at least, on a theological conversation between Scripture and Tradition. If that conversation allows for an evolving theology (e.g. papal infallibility, Marian doctrines, mass changed), then one would think it would allow for other practical and philosophical innovations (political, educational, societal, technology, etc.).

But, as we know, First Things folks—and the orthodox generally—most often argue *against* change/progress, and they most often do it via accusations of heresy. Failing that, they often argue that changes (over time) are merely superficial/apparent so that they can continue to argue for their selection of “first things” (i.e. principles).

Nice post, Tim. The most interesting thing to me is that First Things, or at least Reno, is taking an editorial stance against contemporary conservatism. Do you read it regularly? Is this consistent with its trajectory?

“Consistant” is a high bar, but it does go there, and Reno has demonstrated a desire to steer things in that direction.

This might be seen as a course correction from the Bush years, where the editors regularly sided with neo-conservatism when and where it explicitly contradicted Catholic authorities.

The immediate context for the Reno piece Tim is critiquing here is a piece where Reno critiques capitalism. (For more on that, see: http://www.danielsilliman.blogspot.de/2013/07/even-christian-conservatives-are.html)

I don’t read First Things regularly. I scan it irregularly (e.g. every few weeks) to see where the conversation is going, or headed. From that limited exposure, my sense is that this opposition to contemporary conservatism is new—at least in the broad way articulated by Reno here. But I will accept correction here, gladly.

The most interesting thing to me is that First Things, or at least Reno, is taking an editorial stance against contemporary conservatism. Do you read it regularly? Is this consistent with its trajectory?

Conservatism as libertarianism, yes. Modern liberalism as libertarianism as well, which has been First Things’ primary concern for the past two decades.

It would be unfair to press the term “modernity” too hard with RR Reno here. The “modern” reader, esp in the context of the Roman church, sees modernity as the source of all good, and the Roman church the biggest opponent of it since at least Galileo.

To cut to the chase, Leo XIII [d.1903] and Pius X [d. 1914] condemned “modernity,” offering Thomism as the necessary corrective.

It must be kept in mind that Richard John Neuhaus started as a Lutheran pastor who marched against the Vietnam war. The First Things narrative is that shortly thereafter, what was good Catholic liberalism mutated into leftism, what was Christian solidarity became moral “neutrality”–that’s to say relativism and/or subjectivism replacing the First Thing that there are objective rights and wrongs.

“If you don’t believe in abortion, don’t have one.” There you have it.

It was as a result of that creeping “dictatorship of relativism” that Neuhaus “swam the Tiber” and became Father Neuhaus.

To libertarian economics:

Although American free-marketers such as George Weigel and Michael Novak got the Vatican’s ear [a bit] about the possibilities of free enterprise, Benedict’s signature encyclical Caritas in Verite insists on morality and humaneness as primary in the economic sphere.

Argentine Pope Francis, he of the Second world with one foot in the Third, is at present reminding the Church of its primary mission toward the poor and weak–why he chose the name “Francis,” after the ascetic reformer from Assisi.

It’s all in Leo XIII’s [1891]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rerum_Novarum

Pardon my Wiki. 😉

If you read modernity as “libertarianism” [as “radical individualism,” as moral relativism] yes, it’s there you’ll find the RCC in opposition, be it to Margaret Sanger or Ayn Rand.

Or to Richard Singer or Rand Paul, as the case may be.

[Colleagues: With his permission, Fred Beuttler has allowed me to reproduce here an e-mail, from him, on this post. I’ll reply shortly after publishing. – TL]

———————————————————

Tim,

I read with interest your post in USIH today, on the First Things School of History. I read the original piece too, and was intrigued by how the First Things circle are repositioning their movement in view of recent changes in the culture. I also like your emphasis on the “Second Things,” which is where we historians spend much of our time.

One point I wanted to raise, though, goes beyond some of your comments. A lot of the historical context for First Things itself comes out of Neuhaus’ own biography, which, early in his career, he really did know “a broad range of religiously engaged people who had diverse political commitments.” This was less so during at the beginnings of First Things, but certainly was true in the 1970s and even in the early 1980s.

But that is minor. More significant, I would raise a question at your objection to their claim that they “accepted modernity.” I’m not sure exactly what you mean by “full acceptance of scientific findings, of individual expression and development, … of pluralism?” (I think I may understand at least some of what you mean by “of changed women’s roles.) In the context of Reno’s article, though, he means “the achievements of modernity – democracy, respect for the dignity of the human person, the central role of freedom –“

Here he is affirming the tradition strongly emphasized by John Courtney Murray, which did much to influence some of Vatican II, especially making Rome see that these values are “an integral part of the Christian message.”

Not being Catholic, I’ll dismiss your snarky comments about their dismissal of Catholic ‘theological liberals’ influence, which seem too limited to me after witnessing the health care fight in Congress.

What is more significant, I think, is the legitimacy of the JC Murray tradition, for Reno adds the clause, that democracy, human dignity, and freedom are “sustained and renewed by loyalty to religious authority.”

This is the more important issue here, and goes at the legitimacy of religious conservatism, or even religion in general, in the American context. It may be that the First Things group has “won” against theological liberals and mainline Protestantism, but when you complain that First Things does not accept “pluralism” I take it to mean that you are strictly referring to some form of “pluralism” WITHIN the Catholic Church.

For clearly, JC Murray was a strong component of pluralism WITHIN the CULTURE, and was instrumental in getting Rome to see a legitimate pluralism outside the Catholic Church. But here, I think, is where First Things has a point that should be more forcefully emphasized – that while (as you may be implying) pluralism may have declined within the Catholic Church, would you not also say that pluralism has declined within the larger American culture? Meaning the cultural legitimacy of “loyalty to religious authority,” or rather, the legitimacy of an institutional freedom, and thus, of institutional pluralism? I see a radical weakening of such institutional pluralism, which, whether it is “liberal” or “conservative,” is the foundation of “civil society” and thus of a democratic way of life.

Just some thoughts –

Thanks, Fred

Fred: First things first, thank you for the long, engaged comment.

Point taken on the difference between Neuhaus in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s versus Culture Wars Neuhaus. I saw this in Ray Haberski’s superb study, God and War. I failed to mention it here because of my focus on Reno’s interpretation of the founding of *First Things*.

I’m glad you are questioning my objection to “modernity.” After posting I realized that, had I been more careful (more historical), I would’ve brought up the fact the the meaning of “modernity” has changed, and been used differently, over time. One can appear more and less in tune with modernity depending on which historical era one considers as most representative of “modernity.”

Given that, of course it’s true that Reno (and Neuhaus) were/are “progressive” in relation to 16-19th century Catholicism. And FT Catholics even progressive up to the John Courtney Murray era of moderately progressive Catholicism (i.e. 1950s). That can include iterations of democracy, iterations of thinking about freedom, and respect for the dignity of the human person. But that’s progressive as defined within the Church itself (theologically and socially). But I’ll go ahead and give you some degree of “progressivism” despite the fact that many orthodoxy-centered First Things Catholics—traditionalists—reject all forms of modernity by definition. This is why you can find Ultramontane style Catholics even in America (modified after VCII as excessive fetishism of the teachings of the Magesterium, without compromise).

As you well know, Fred, there are several iterations of those three areas of progress that orthodox, First Things Catholics reject and/or deeply question (given of course FT Catholics are not monolithic). Let’s go through them:

Democracy: Even when they profess allegiance to American-style representative democracy, you can find elitist strains in the thinking of FT Catholics (e.g. George Weigel). These elitist strains include a strong, jingoistic focus on neoconservative American domination in the international sphere (pro-war w/out limits). Universal respect for all forms of democracy is not a consistent trait among FT Catholic thinkers. They think globally (sometimes, when they’re not excessively focused on front-porch-style localness, a la Patrick Deneen), but they’re not cosmopolitans in favor of majority rule democracy.

Human dignity/rights: Most often this is restricted to a fetishization of abortion as THE HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUE of the late twentieth century. There’s little focus on the causes of abortion and prevention, just prohibition (via a potentially large state apparatus, I might add).

Freedom: As distributist, small-scale communitarian/libertarians (at their best, I emphasize), FT Catholics are often willing to sacrifice larger apparatuses of social justice to achieve their dream of scale. In so doing they undermine freedoms for large classes of people (blacks, women, Hispanics) whose status as citizens is protected by larger federal and state institutions. In this way I suggest that FT Catholics are, implicitly, opposed to full pluralism. I define pluralism in the state as a status where one’s full participation and baseline welfare as a citizen is vigorously protected. This cannot be the case in a distributist, confederate, deregulated environment.

In sum, the John Courtney Murray strain of FT thinkers is more the exception than the rule. Check out the Wikipedia link to Murray above; potentially big theological/social philosophical differences between him and FT thinkers are fairly obvious.

I apologize for the big generalizations above. But I find, at base, the problem of distributism/subsidiarity—a philosophical/theological position that is a “first thing” among many orthodox Catholics—undermines many of Reno’s claims to shared universal values. – TL

Can somebody tell me why the largest, most obvious, most well-funded, and most effective weapon in the culture wars is always excluded from the discussion? I mean, of course, advertising.

Well, Thomas Frank’s *Conquest of Cool* speaks to your topic. He argued (and what follows is radically simplified) that corporations coopt the latest thing, selling ironically the atmosphere of cool detachment while still pulling money from your wallet. They sell the anti-capitalist mode of being—a feeling. And he discusses how niche marketing has helped us not see the trend overall. I don’t think Frank directly addressed the Culture Wars, but his book is discussed among scholars who try to understand cultural fragmentation and how marketing undermines solidarity even among those opposed to capitalism. …But perhaps you already know about Frank’s early, highly-respected scholarly work?

John, I’m happy to say that advertising is something I’m looking at — in some very surprising places, I must say — for my dissertation on the 1980s “canon debates.” And I think my colleague Tim Lacy also looks at advertising in his study of the “Great Books” idea.

That’s about all I can say about my own work for now. But, more generally, I would say that an intellectual history approach that pays attention to all kinds of texts, broadly construed, is preferable (for me) over the kind that focuses only on the texts / arguments that were “self-consciously” intellectual.

Anyway, this is a smart comment, and a good reminder that ideas are everywhere, and sometimes the ideas with the least prestige have the most pull.

I do indeed look at Britannica’s advertising methods (i.e. its cottage industry) in relation to selling the *Great Books of the Western World*. Now that’s in no way a co-opting of cool, a la T. Frank, but my work gets at how an entity sells/sold culture in the midst of the Culture Wars.

to a fetishization of abortion as THE HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUE of the late twentieth century

For the RCC, abortion is non-negotiable for the same reason euthanasia is non-negotiable: You can’t be a “little bit” pregnant or make someone just a little bit dead. It’s the essential and absolute nature of these issues more than a question of emphasis, and why it’s abortion and euthanasia that are paired in the Church’s rhetoric. Cardinal Ratzinger 2004:

Otherwise, the Roman church–especially the American bishopric–has largely been on the side of your party historically when it comes to “social justice.”

There’s little focus on the causes of abortion and prevention, just prohibition (via a potentially large state apparatus, I might add).

The RCC is among the foremost providers of adoption and health care services in America. But as we saw with the gay adoption issue in Massachusetts, the Church sees itself being pushed via the apparatus of the state toward a formal cooperation with evil–and in that case its only alternative was to abandon adoption services altogether. If the Church is not to abandon the engagement with the real world it’s often accused of not having, a line must be drawn.

http://www.hprweb.com/2012/09/avoiding-cooperation-with-evil-keeping-your-nose-clean-in-a-dirty-world/

[Relayed, with permission, from Fred Beuttler. – TL]

——————————————————-

Tim,

Thank you for your measured reply – I had seen it late on Friday, but was at a long workshop so couldn’t respond in the form that I wanted. And now this morning I see that there are several other posts, moving this thread in a couple other directions.

This may not be the place, then, to explore all these ideas that come from your original post on First Things. But there is something that I do want to comment on. My point is not to defend First Things style Catholicism, although I have been a reader on and off since its beginning. But rather to use your comments to open up some larger discussions.

Taking up your three areas, of “Democracy,” “Human dignity/rights”, and “Freedom,” I’d like to focus on the latter. You’re right that there is a strong elitist strain in some FT Catholics, and much of the FT crowd closely follows an American neo-con model in a lot of things, or even a straight-out American conservative line. Your brief comment on the “fetishization” of abortion has been adequately knocked down by Tom Van Dyke, that the Romanists do have a lot of prevention and other health care issues. One day I’ll have to write about the negotiations that took place in the House over Obamacare on these issues.

But the real significant comment of yours is when you discuss “Freedom,” in this context. Let’s open this up a bit, for here is a strain that the First Things crowd is reminding us of a number of very important things.

You’re probably right that the FT Catholics are “distributist, small-scale communitarian/libertarians,” who do have a nostalgic streak, often pining for some rural peasant paradise. I remember reading Neuhaus once praising New York City as a collection of small neighborhoods, kind of like the ethnic parishes that once made up most of Chicago. You’re right, too, that small-scale communitarianism does sometimes “sacrifice larger apparatuses of social justice,” which is one basis of the expansion of freedom for blacks, women and (possibly) Hispanics.

That misses my point though, for, based on John Courtney Murray’s ideas, they really are more pluralist institutionally than most Americans. Again, I’m not here to defend First Things Catholicism, which, since I’m not Catholic, would be tricky on my part anyway. But the idea of the “freedom of the Church,” is what is really at issue here, is it not? If you define “pluralism” as you do, as “in the state as a status where one’s full participation and baseline welfare as a citizen is vigorously protected,” I probably agree with you. But that is not how they define it, nor how I would.

Let’s go back to John Courtney Murray, rather than the more journalistic First Things editor, who admittedly is writing to a more short term audience. For Murray does emphasize an institutional pluralism, best represented historically by the Roman Catholic Church, but, I would argue, has analogous developments beyond. [The doctrine of “subsidiarity,” though, is way too weakly developed in Catholic doctrine, unfortunately.]

In reading Murray, one of the more relevant pieces for this discussion is his “Are there Two or One?,” from We Hold These Truths (1960). http://woodstock.georgetown.edu/library/murray/whtt_index.htm , with the actual chapter, here: http://woodstock.georgetown.edu/library/murray/whtt_c9_1957b.htm

Murray is grounding an idea of human freedom as based in part on the doctrine of the “Freedom of the Church,” a Christian view based on “a radical distinction between the order of the sacred and the order of the secular: ‘Two there are, august Emperor, by which this world is ruled on title of original and sovereign right—the consecrated authority of the priesthood and the royal power.’” This statement by Gelasius I in 494 AD, Murray considers the “magna charta” of the medieval church, which was reaffirmed countless times, especially by Pope Leo XIII. It has two principles, the freedom of the Church as a spiritual authority, and the freedom of the Church as “the Christian people.” This provides “the inherent suprapolitical dignity of this life, and ‘the enjoyment of the right to live in civil society,” including all such institutions which “transcend the limited purposes of the political order,” and thus are “sacred.” For Murray, the chief example is the family, but he also includes other institutions which are outside of the purview of the state, such as the “employer-employee relationship,” although he clearly states that this could “require regulation in the interests of the personal dignity of man.”

Putting it a little closer to home for us intellectual historians, Murray also calls sacred “the intellectual patrimony of the human race.” That of course means the medieval institution of the University. For isn’t the idea of a university an intellectual community that extends beyond the nation, which is “sovereign” in itself? There is no “bourgeois physics,” for example.

This is a doctrinal basis for the separate sovereignties outside the State, which serves as “the limiting principle of the power of government.” In a secular form, Murray sees the distinction between State and Society as the political outgrowth of this Christian distinction between Church and State, the “Two.”

The rise of the modern state, however, was in direct response to divided sovereignty, as it violated the integrity of the political order. Hobbes and Rousseau attacked this “Two” directly, as Hobbes said: “Temporal and spiritual government are but words brought into the world to make men see double and mistake their sovereign,” Leviathan. This Murray considers the “most salient aspect of political modernity. Over the whole of modern politics there has hung the monistic concept of the indivisibility of sovereignty: ‘One there is.’”

So, in this sense, the real pluralism is an institutional pluralism, of a form of “sphere sovereignties” outside the power of the state. Perhaps this could be seen as “the Many.” The First Things Catholics see “Freedom” in the form of “freedom of the Church,” as an independent sovereignty, a “Two” over against the “One there is.” I would suggest that the larger issue, of which the FT point is a type (in the typological sense), is that human freedom and flourishing requires institutional pluralism, a Many, of which your definition, being merely within the monistic State, while important, is still too limited to support the broader notions of human freedom. Historically, the Many-s may have required the power of the Two to carve out free space from the One, but the One can overwhelm the many Many’s without the legitimacy of the Two.

My question then moves outside the immediate discussion of the First Things Catholics, and instead seeks to see if Murray does have a deeper point – is human freedom and flourishing based on this institutional pluralism? Of a form of Madisonian “multiplicity of interests,” but in a more fundamental sense, of a number of sovereignties: Are there Two, or One, or Many?

– Fred

Fred,

Thanks again for the long, thoughtful comment. I’m completely fine with this discussion going in different directions. I won’t, however, *directly* reply to TVD’s comment because it gets too close to present abortion politics and I don’t want to go too far down that road here. [Suffice it to say, however, that I don’t think one can draw a direct line from historical forms of Catholic political engagement, say from the 1930s to the 1980s, to today—to the kinds of engagement policed by conservative FT Catholics as “proper.”]

This move towards John Courtney Murray is interesting. I need to read more about the particulars of his theological positions (contextually), and how they transfer to the present. I don’t know, for instance, what/if Murray wrote on subsidiarity. I’ll have to read and ruminate on the documents you supply above. Thank you for them.

It seems to me that the simple fact that Murray was willing to risk being silenced for his position(s) puts him outside the kinds of figures that inspire FT Catholics today. That appearance of unorthodoxy would turn off Culture Wars Catholics. Am I on to something here?

I do see your point about FT Catholics trying to “protect”/live out the freedom of Catholicism in partnership with the State. These smaller sovereignties—attached to universal issues—do matter. There are many, but there is a hierarchy (nested communities).

But I think many FT adherents take it further (e.g. Wiegel), and want Catholic positions institutionalized, at all costs *and* immediately. This shrill lack of patience (i.e. inability to accept temporary compromises) on a few issues has compromised many of their larger more admirable goals in the political sphere and marginalized, overall, the bigger goals of Neuhaus and other FT founders. There’s no sense of a long game, just short-term demands. …See how I’m talking tactics and strategy without going down the road of some obvious political issues (such as the one I declined to discuss further above).

– TL