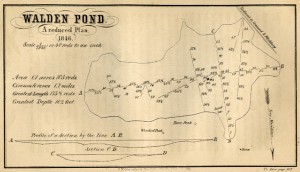

When Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau met in 1856, they didn’t like each other. Both were poets of nature, but Whitman surrounded himself with myriad blades of grace while Thoreau sat solitary by his pond, traced its circumference, measured its width and its deepest point. After their meeting, each poet privately recorded his dismay that the other had so much faith in, or was so cynical about, the democratic character of American life. (Some scholars argue that the audacious optimism of Whitman’s poetry masked a deep insecurity; let this serve to excuse him for his dismay at Thoreau’s cynicism about American democracy six years after the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, two years after Kansas-Nebraska, and four years before the Civil War!)

When Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau met in 1856, they didn’t like each other. Both were poets of nature, but Whitman surrounded himself with myriad blades of grace while Thoreau sat solitary by his pond, traced its circumference, measured its width and its deepest point. After their meeting, each poet privately recorded his dismay that the other had so much faith in, or was so cynical about, the democratic character of American life. (Some scholars argue that the audacious optimism of Whitman’s poetry masked a deep insecurity; let this serve to excuse him for his dismay at Thoreau’s cynicism about American democracy six years after the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, two years after Kansas-Nebraska, and four years before the Civil War!)

Thoreau, the symbol of American individualism, and Whitman, the democratic spirit incarnate, were two of the names I heard last week in Shanghai, when I told a Chinese graduate student in education policy that I studied American history and “the history of ideas” (the other names were Socrates and Kant). This Chinese student had studied Thoreau and Whitman in English and in Chinese translation, and he light up when I affirmed that I had studied them and loved them, too. We didn’t speak for long, but this encounter, aside from reminding me of the supreme power of compelling ideas and memorable books to create community among otherwise unconnected people– a topic worthy of its own intellectual history– led me to examine some of the reception history of Thoreau and Whitman in China.

In an article published in 2008, Jincai Yang, professor of English at Central China Normal University, explains that Thoreau has been examined in China for his potential similarities to Toaist thought, hailed during the Cultural Revolution as a critic of America and American capitalism, and, most recently, embraced as an environmentalist.1

Ed Folsom, professor of English at the University of Iowa, argues that Chinese readers view Thoreau and most other English-language as foreign imports, interesting and valuable, but of another wold. Walt Whitman, however, is a different story. Whitman in China, claims Folsom, is a Chinese poet. Where Whitman heard America singing, Chinese readers have heard the voice of revolution and democracy, the voice of the people. Since the early 20th century, Chinese revolutionaries have lovingly examined Whitman for that voice, and for the same democratic voice the Chinese government blocked the publication of a new translation of Leaves of Grass in 1989.2

Over the past decade, scholars have created several conferences and organizations promoting the study of American literature in China. This month the Chinese/American Association for Poetry and Politics (CAAP) holds its second conference in Wuhan, China. Organizers of these conferences explain that their goals are to bring both Chinese and American literature into a global context, to make studies of American literature global, and bring international voices into American lit criticism. One could write a history of the development of this kind of international community organized around a national literature. This history could include the exportation of American literature abroad during the Cold War, but existing studies on that topic have focused almost exclusively on Europe, and have begun in 1945. We should have a history of the global reception and discussion of national literature that predates the Cold War and is not limited to the United States and Europe.

What I found most interesting about my Chinese friend’s excitement over Thoreau and Whitman, as opposed to his interest in Kant and Socrates, is those poets’ particularly national context, their poetry’s exquisitely American aesthetic, and its rootedness in American geography. My Chinese friend had never left China; he read Walden in Shanghai. The first time I read Walden I was on a family vacation in Boston, and I had circled the pond and stood in the little reproduction cabin that sits near the entrance before I finished the book. I believe my experience with Walden was no more “authentic” than this Chinese student’s experience, an idea that should be perplexing, challenging, perhaps liberating. Both of us created Thoreau’s Walden Pond, Thoreau’s America. Thinking about American literature in an international context can lead to a fascinating national self-understanding through an examination of how America is constantly imagined and reinvented—not just when Whitman revised and revised and revised his lines, but when people read and reread them.

Thoreau and Whitman, in particular, are prefect lenses through which to view how America has been imagined and invented, because they represent two distinct personalities struggling with perhaps the central questions of American history: how to reconcile the individual with society, or how to balance Whitman’s impulsive faith in the people with Thoreau’s carefully protected morality. Historians should listen to these questions as they have been expressed and addressed, as if in dialogue with American ideas and symbols, in an international context. The case of China, with its turbulent history of uprising, revolution, populist rhetoric, and government repression, combined with its rapidly changing present, is a fascinating place to start.

has been imagined and invented, because they represent two distinct personalities struggling with perhaps the central questions of American history: how to reconcile the individual with society, or how to balance Whitman’s impulsive faith in the people with Thoreau’s carefully protected morality. Historians should listen to these questions as they have been expressed and addressed, as if in dialogue with American ideas and symbols, in an international context. The case of China, with its turbulent history of uprising, revolution, populist rhetoric, and government repression, combined with its rapidly changing present, is a fascinating place to start.

_____________________________________

1 Jincai Yang, “Chinese projections of Thoreau and his Walden’s influence in China,” Neohelicon December 2009, Volume 36, Issue 2, pp 355-364.

2 David Hulm, “America’s poet of comrades: Walt Whitman in China,” 2008.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Great post! I am always excited to see trans-Pacific intellectual history work being done, since I have found it to be a largely neglected field. If you’re interested, there has been some work done on John Dewey’s trip to China in the early 1920s and its impact on Chinese thought. The most recent book on the topic is Jessica Ching-sze Wang’s “John Dewey in China: To Teach and To Learn” (2007).

Great, thank you!

Fascinating post! Left me thinking about the reception of Thoreau in Latin America (Whitman has inspired generations of Latin American poets to write with him and against him). What about Emerson, where does he fit within the Chinese narratives?