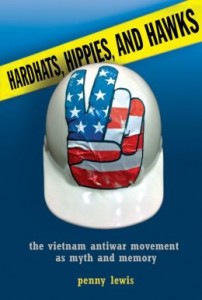

In the recent issue of the Chronicle Review, Penny Lewis has a brief essay on the subject of her latest book entitled, Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks: The Vietnam Antiwar Movement as Myth and Memory (ILR Press, 2013). Her argument seeks to correct the misplaced emphasis on liberal elites as the engine of the antiwar movement. Rather, Lewis contends, “the notion that liberal elites dominated the antiwar movement has served to obfuscate a more complex story. Working-class opposition to the war was significantly more widespread than is remembered, and parts of the movement found roots in working-class communities and politics.” Lewis notes that the most consistent support for the war came from the “privileged elite.” Thus by addressing the question of “who opposed the Vietnam War?” Lewis forces us to contend with the idea that those who opposed the war did not distribute themselves neatly into cultural boxes–opposition to the war appealed to and cut across categories of race, class, and gender. In short, the image of working class hardhats attacking elite, college-educated kids does not tell the whole story.

In the recent issue of the Chronicle Review, Penny Lewis has a brief essay on the subject of her latest book entitled, Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks: The Vietnam Antiwar Movement as Myth and Memory (ILR Press, 2013). Her argument seeks to correct the misplaced emphasis on liberal elites as the engine of the antiwar movement. Rather, Lewis contends, “the notion that liberal elites dominated the antiwar movement has served to obfuscate a more complex story. Working-class opposition to the war was significantly more widespread than is remembered, and parts of the movement found roots in working-class communities and politics.” Lewis notes that the most consistent support for the war came from the “privileged elite.” Thus by addressing the question of “who opposed the Vietnam War?” Lewis forces us to contend with the idea that those who opposed the war did not distribute themselves neatly into cultural boxes–opposition to the war appealed to and cut across categories of race, class, and gender. In short, the image of working class hardhats attacking elite, college-educated kids does not tell the whole story.

Lewis’s essay reminded me of a study I came across when I was trying to figure out how Americans responded to and debated the moral implications of Vietnam. In 1979, William Lunch and Peter Sperlich published a study, simply entitled “Public Opinion and the War in Vietnam,” in the Western Political Quarterly (v. 32, March 1979). Their data demonstrated that support for the war was strongest among the youngest Americans polled. For example, in March 1966, in polls that asked “In view of developments since we entered the fighting in Vietnam, do you think the U.S. made a mistake sending troops to fight in Vietnam?” 71% of Americans age 21-29 responded “No” to this question, whereas 48% of Americans age 50 and over responded “No” to the same question. Jump forward to May 1971, and the numbers for these two groups, respectively, were 34% and 23%–with the younger generation still showing more support for the war than their elders. When looking at different options in the war, in regard to those younger than 35 years of age polled in 1964, only 11% supported withdrawal, while 49% supported escalation; in regard to those over 35, 19% supported withdrawal and 40% supported escalation. By 1971, that configuration remained consistent.

Their research also illustrated that from the beginning of the war, those on the lower end of the income spectrum supported withdrawal and opposed escalation at higher rates than those with higher incomes. But more to the point that Lewis makes, data from this study also demonstrated there was considerable agreement about the war among working class Americans of all ages, color, and gender and those Americans who had post-college education and who had incomes above the middle class. Among the most interesting data points in the study was that from 1966 to 1969 (roughly from the Fulbright hearings to Nixon’s election in ’68), young, white, middle-class, religious, college-educated men, overwhelmingly supported the war.

Support for the war certainly waned among all groups in the early 1970s, but considering what Lewis suggests about who opposed the war, we might need to reconsider our terms. It wasn’t the protesters who stood apart from “ordinary” Americans by opposing the war but rather those who supported war. Considered in these terms, ordinary Americans were those who opposed the Vietnam War and did so throughout its history, while a very specific subset of Americans maintained their support for the war. If we do try to get at some understanding of what is “ordinary” or “typical” in American experience, should we rethink the American relationship to war?

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Fascinating stuff, Ray! Of course the dominant (and apparently false) images of both elitist anti-war protestors and “normal,” working-class war supporters were self-consciously produced (or at least encouraged) by the Nixon Administration, as Rick Perlstein and others have argued. And these images quickly gained enormous cultural traction (e.g., Norman Lear essentially bought into them in creating–well, adapting from their British source– the characters of Archie Bunker and Mike Stivic on that quintessentially liberal sit-com, All in the Family (1971-79)) So my immediate question is: given the distance between these images and political reality, why was Nixon so successfully able to use the image of the privileged, elite anti-war protestor as a symbolic political wedge? I guess I’ll have to read Lewis’s book!

Great post, Ray, and wonderful follow-up question, Ben! I was thinking about how these findings complicate what we “know” about the churches and the war. Take Jill Gill’s exhaustive study of the National Council of Churches and Vietnam–Embattled Ecumenism–for instance. The common wisdom seems to be that the “patriots in the pews” began the break-up of “mainline” identity and support because of their differences with antiwar ecumenical “elites.” That infighting allowed increasingly nationalistic and prowar conservative evangelicals to fill in the public theological gap since 1970. So, where and are “plain folk” evangelicals a new part of that “very specific subset?”

Indeed, Ben, I think your question is at the heart of Lewis’s book. We’ve had discussion on the blog before regarding the contrast between memory and intellectual history, and I think your question also suggests the tension between a notion that becomes an assumption and an idea that develops in relation to its political and social context. Perhaps along the same lines as Perlstein’s insight into Nixon’s political strategy, and to speak to Mark’s comment below, Richard John Neuhaus wrote an essay in 1970 in which he identified the growing distance between church leaders and congregants caused by the war but not solely about the war. For Neuhaus, who opposed the war, the war exposed a growing dissatisfaction with the idea of America as a moral place and so he saw a time emerging when a new religious understanding of redeeming the nation would arrive in wake of the fall-out from the war. So I see Neuhaus almost predicting the Reagan turn toward a muscular civil religion without really committing to a militaristic foreign policy–real war actually causes problems, but the metaphor of war creates coalitions.

Thanks Ray.

If I’m not mistaken, in the early part of the war the draft drew mostly from lower class population because of lack of deferment or influence (political or financial). When the lottery came into play, I think ’71-’72, didn’t the draft affect a broader spectrum of the population? The reason being the temptation to expose one self to the draft (once exposed and un-drafted you were no longer at risk of being drafted in the future, ergo the use of the word lottery) with the hope of avoiding the draft altogether resulted in a formerly inaccessible demographic. If my memory is correct this might have some explanation for the results above. Have there been any studies on the class equitability of the draft or the influence of the draft on popular opinion?

From 1966 or 67 on, the only thing that kept middle/upper middlec class kids (like me) from getting drafted was the college student deferment. Because I was too busy doing anti-war stuff in 1968 while in the political science PhD program at Michigan, I got a couple incompletes and promptly received a draft notice. During my draft physical, I agitated against the war, and after a cursory FBI investigation, all of a sudden got my student deferment back – without even having asked for it. At that point, they were still deciding to not bother with people who were obviously more trouble than they were worth. Increasingly after that, people started doing all kinds of things during draft physicals – wearing women’s underware was popular. The authorities stopped being influenced by such things and took everybody. Between that time and the move to a lottery in the early ’70s, middle/upper middle class opposition to the war took off. But in my earlier experience, 1964-68, it was always true that the anti-war movement was predominantly peopled by middle class college students + old lefties and their kids, including what was left of such in the labor movement. The mainstream of the AFL was not in the forefront by any means, in fact was quite hostile.

Paul, those are excellent questions, and I have not run across the kind of studies you suggest. I imagine that they exist, but I do not know of any. Lewis does write about these issues, and she refers to this book: http://www.amazon.com/Chance-Circumstance-Draft-Vietnam-Generation/dp/0394412753

as a source as well.

Did Lunch and Sperlich conduct any more studies? Or has anyone else followed up on their work? – TL

Tim, there have been some interesting quantitative studies on views of war. Check out The Casualty Gap: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0195390962/ref=oh_details_o01_s00_i00?ie=UTF8&psc=1

This looks like a remarkable book. I don’t doubt the premise/argument of this one (if the Amazon summary is correct).

I’ve always been interested in and impressed by the many veterans who came out against the war. And, not surprisingly perhaps, I will take advantage of this discussion to let folks know I have a select bibliography on the Vietnam War that–like all my other compilations (several of which I recently updated)–I will send along to anyone interested (in Word or as pdf).

Super post, Ray. It’s interesting to witness this particular historiographic moment, when “the narrative” (as if there were just one) of the sixties is being re-examined and reframed by historians for whom the era is not some mix of memory and history, but is “all history.”

I know, I know — the attempt to draw a line between “memory” and “history,” even for heuristic purposes, opens several cans of epistemological worms. But it’s a problem worth thinking about, especially as the evidentiary arguments of the historians begin to diverge from the memory of the participants.

Not to imply that they are in any real disagreement, but there is always this question — whose account would one credit as being more “true” to the temper of the times, one based on recollection of personal experience (perhaps confirmed by “history,” or one version of it) or one based on a more “empirical” examination of archival / primary sources.

It seems that many histories have been written by people who rely on some combination of both. But the farther we get from the 1960s, the less that will be. So I wonder how much “the narrative” will change, and in what ways. But this book sounds to me like a very interesting account and a bold (and, apparently, sound) historiographic move.

I’ll be glad to read this book — if I’ll ever again have time to read books I don’t have to be reading.

I’d have to echo the comments above. This book does open up some intriguing discussions about history and memory as it relates to the 1960s. Of course, when we write about the Sixties, we have to realize as historians that we’re often writing against established public memory of the decade. Political rhetoric since the end of the Sixties has colored perceptions of the era, which is not surprising. I also have this book, and now I’m really eager to read it, if only to see how people of the Sixties saw themselves as being “anti-war”. Did it trump for them class, race, and gender divisions? I think it may depend on the group, but of course I’m typing all this not yet having read the book.

A book like this fits into a larger vein of works that are asking some serious questions about recent American history. I’m thinking about works as disparate as Sokol’s “There Goes My Everything” (which forces readers to think more about white Southerners, which is where the field Civil Rights History is really starting to delve into) as well as Robert Self’s “All in the Family”, among others. It’s an exciting time to study American history from the Sixties and Seventies, with so many questions still waiting to be answered, re-examined, and reconceptualized.

Drafted in 1965 after dropping out of grad school–didn’t meet many college graduates in the ranks, a fair number of enlistees, but we were almost entirely lower middle class. The lottery went into effect for 1970 calendar year inductions.

My memory is that the white college grads seemed to dominate the news media coverage of the anti-war movement, perhaps because the flashiest and most attention getting groups were people like SDS and the Weather Underground, just memorialized in Redford’s new flick: The Company You Keep.

Her argument seeks to correct the misplaced emphasis on liberal elites as the engine of the antiwar movement. Rather, Lewis contends, “the notion that liberal elites dominated the antiwar movement has served to obfuscate a more complex story. Working-class opposition to the war was significantly more widespread than is remembered, and parts of the movement found roots in working-class communities and politics.”

Wow, Ray. Great stuff. Pardon my Wiki: The Vietnam War loses majority support by June 1967, Tet [Feb ’68] helps sink LBJ, but then it appears the “anti-war” demonstration fad dies down by mid-1970 or so.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opposition_to_the_U.S._involvement_in_the_Vietnam_War

Nixon’s approval ratings remain high from his January inauguration in 1969* until Watergate breaks in Spring 1973, about the same time the last US combat troops leave Vietnam.

_____

*Via AEI [linked in Wiki]: “In March 1969, almost four years after the country had sent a half-million troops to battle, just 19 percent said they favored ending the conflict “as soon as possible,” 26 percent wanted the South Vietnamese to take over, 19 percent wanted current policy to be continued, and a third were in favor of the United States going all out for a military victory.”

________

Although support for the war has sunk well below 40%, End the War Now anti-war opinion is held only by 1/5 of the country. The real face of the Anti-War “movement” may be the Nixon voter, who, judging by the demonstrations dying down and Nixon’s consistently strong approval ratings, is fairly content to wait for “Peace with Honor,” although it takes another 4 years.

Contrary to somebody’s cherry-picking, to full Gallup polling sequence (via Wikipedia) is as follows:

“Public support for the war decreased as the war raged on throughout the sixties and beginning part of the 1970s.

William L. Lunch and Peter W. Sperlich collected public opinion data measuring support for the war from 1965–1971. Support for the war was measured by a negative response to the question: “In view of developments since we entered the fighting in Vietnam, do you think the U.S. made a mistake sending troops to fight in Vietnam?”[38] They found the following results.

Month Percentage who agreed with war

August 1965 52%

March 1966 59%

May 1966 49%

September 1966 48%

November 1966 51%

February 1967 52%

May 1967 50%

July 1967 48%

October 1967 46%

December 1967 48%

February 1968 42%

March 1968 41%

April 1968 40%

August 1968 35%

October 1968 37%

February 1969 39%

October 1969 32%

January 1970 33%

April 1970 34%

May 1970 36%

January 1971 31%

May 1971 28%

After May 1971 Gallup stopped asking this question.”

Of course there’s lots more polling data from a wide variety of sources (which I haven’t checked), some considerably more reliable than Gallup. But the more important point is that with this kind of question, there is always going to be a large amount of non-sampling error, including, very likely, frequent major “social desirability” effects, resulting in unknowable levels of variance from random results. The stated “margin of error” is pure fiction. About all the above results should lead you to say would be that it’s probably true to say that through 1967, somewhere around one-half of whatever population was actually being sampled and was actually answering the question in Gallup polls was responding in a way that caused the interviewer to code them as more positive than negative re U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, whereas after that, 1968-71,negative responses increased steadily, such that only about a third to a quarter held back from saying things that caused the interviewer to code them as negative re the war.