I was asked to give a talk to undergrads about the historiography o f race and gender in U.S. History. Given my interests, I have narrowed that down further to “The Course of Black Women’s Intellectual History” (since the Historiography of History was too much of a mouthful). See my prezi here

f race and gender in U.S. History. Given my interests, I have narrowed that down further to “The Course of Black Women’s Intellectual History” (since the Historiography of History was too much of a mouthful). See my prezi here

.

I’m going to start with three questions:

- What is historiography?

- Who are intellectuals?

- How have black women changed the historiography of U.S. Intellectual History?

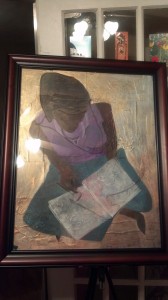

In my prezi, I put these questions on the book in the picture to the side. This is my painting that is hanging in my office and I thought it was a nice symbol of black women’s intellectual history. Perhaps it is also slight self-promotion of my own artwork, but hopefully no one minds. Once we have discussed the first two questions and posed the third as the overarching question of the next thirty minutes, I will go through the following outline. I will be handing out quotes to the students for them to guess which quote goes with which historiographical moment as an attempt to make historiography interactive (I’m very interactive in my teaching, but this was a difficult one for which to think of interactivity).

- A void in black women’s history

- (but not really, because there are assumptions about the ability of black women to think…i.e. U.B. Philips work).

- There were black men and white women writing in history in this early period (defined as pre-Civil Rights Movement), but black women have been restricted from history because, as Bonnie Smith writes,

“Only in the world of disinterested contemplation–a world necessarily separate from emotional, subjective women, whose concerns hovered around the quotidian–could real history–that of wars, politics, and important men–be written. Professionalization was, therefore, a means of exclusion. It was gendered male and, by and large, raced white.”

- I will mention Anna Julia Cooper as the first black women to get a Ph.D. in history (from the Sorbonne in 1925) and as a prominent intellectual who struggled to professionalize her degree.

2. The explosion generated by the Civil Rights movement and the Women’s Rights Movement.

- Black men’s intellectual history (August Meier)

- White women’s intellectual history (Linda Kerber)

- But together still not yet

- (as well as a downward slide in intellectual history)

3. Black history and women’s history come together through the example of Darlene Clark Hine. In Telling Histories: Black Women Historians in the Ivory Tower, she writes about her own experience in graduate school

“I did not question the implicit assumption of my teachers, all of whom were men, that whatever was said about black men applied with equal validity to black women, who apparently rarely, if ever, ventured beyond the domestic sphere. With the exception of Phillis Wheatley, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman, black women were voiceless and faceless in history texts.”

“Perhaps I am being too hard on myself, but the point is that I was oblivious to the lack of attention that I and others paid to black women’s experiences.”

“Because I possessed no framework or perspective from which to evaluate or interpret the significance of their efforts to the success of the larger objective, I left black women on the periphery.”

Then a group of Indiana women asked her to write their history and, when she argued that there would not be enough sources, showed up on her doorstep with hundreds of boxes of primary material. Through her work on their topic and an extensive list of other works, she helped create the field of Black Women’s History (Rosalyn Terborg-Penn had already started the field, but Hine helped nationalize its study).

4. The study of Black Women’s History in general generates books on Black Women’s Intellectual History (after adding and subtracting and adding and subtracting, I have decided to focus on just a couple of books).

- All the Women are White, All the Blacks are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies, edited by Gloria T. Hull, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith, 1982

“Merely to use the term ‘Black Women’s studies’ is an act charged with political significance. At the very least, the combining of these words to name a discipline means taking the stance that Black women exist—and exist positively—a stance that is in direct opposition to most of what passes for culture and thought on the North American continent. To use the term and to act on it in a white-male world is an act of political courage.”

- Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins, 1990, 2000, 2009

“Black women intellectuals have laid a vital analytical foundation for a distinctive standpoint on self, community, and society and, in doing so, created a multifaceted, African-American women’s intellectual tradition.”

- Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol, Nell Irvin Painter, 1997

“I showed her as a person whose individual psychology counts alongside her role as a symbol. But many people just want a symbol, unchanging and undisturbed by psychological development. “

- 2011 Conference: “Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women”

Then I will offer an answer to the overarching question of the day:

- How have black women redefined U.S. Intellectual History?

- Necessity of race, class, and gender analysis (intersectionality)

- Redefined what it means to be an intellectual

- Inextricable link between ideas and praxis (Collins: “African-American women’s intellectual work has aimed to foster Black women’s activism.”)

5. How does my work fit into this historiography?

- Adding Black Women

–Black Internationalism

–Accommodation and Protest

- In conversation with the insights of black women’s intellectual history

–Patricia Hill Collins: All black “women’s intellectual work has aimed to foster Black activism.”

–Claudia Tate and Nell Irvin Painter: Individual subjectivity

Now the primary question is: will all this really fit into 30 min? I’m practicing today, so we’ll see. The next question: Is handing out the quotes and having the students guess as to which one fits enough interactivity. And the third: Did I miss the boat on something major? Would you suggest adding or subtracting anything?

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I would argue that the failure to begin with the 1978 publication of The Afro American Woman: Struggles and Images is a gross oversight. The group of women who published the work also established the Association of Black Women Historians at the same time. I suggest you also read Rosalyn Terborg-Penn’s chapter in Telling Histories to ground your discussion on Black Women’s Intellectual history. Lastly, I would suggest you also center, Beverly Guy-Sheftall’s seminal text, Words of Fire, in your discussion of Black Women’s Intellectual history and Black Women’s Studies.

All the best

Thanks for your comment!

I decided to highlight Darlene Clark Hine’s contributions rather than Rosalyn Terborg-Penn in part because I worked with her briefly at MSU and in part because her story about not recognizing the value of black women’s history in the beginning of her career is so stark and interesting. But I completely agree that Terborg-Penn’s contribution to black women’s history, as well as the founding of the ABWH, were both foundational to black women’s intellectual history.

I will see if I can incorporate your suggestions without making the talk longer.

Thanks again!

May I also recommend Stephanie Evans, “Black Women in the Ivory Tower, 1850-1954: An Intellectual History.” I’ve used it before in teaching a class on race and higher education in the United States, and the students reacted very strongly to both the intellectual contributions and analyses of the women in the work AND their personal experiences dealing with racism and sexism in the academy.

I had it on my original list and cut it for time constraints. But great suggestion! I’m glad to hear students engage well with it.

Given your topic, I recommend my forthcoming work, Recovering Five Generations Hence: The Life and Work of Lillian Jones Horace, Texas A & M University Press, forthcoming April 19, 2013. Lillian Jones Horace (1880-1965) is Texas’s earliest known African American woman novelist and one of only two black women to own a publishing company before 1920. Horace’s first novel, Five Generations Hence and her others literary contributions affirm Patricia Collins’s statement that black “women’s intellectual work has aimed to foster Black activism.” Essays on Horace have been published in the following refereed journals: Mississippi Quarterly, Black Women Gender and Families, and East Texas Historical Journal.

Thank you! I will look out for your work. It sounds fascinating.

May I ask how her novel affirms Collins’s statement?

The views and philosophy of Lucy Diggs Slowe are worthy of presenting to students. She was passionate about women’s contribution to the social order. See a collection of her speeches and writings in “Faithful to the Task at Hand: The Life of Lucy Diggs Slowe” by Carroll L.L. Miller and Anne S. Pruitt-Logan, published june 2012 by SUNY Press.

I find Lucy Diggs Slowe fascinating and use her letters to Juliette Derricotte in my work. I wasn’t aware of your book till now. I will definitely look it up!