Wherein a Professionally-Trained Historian Reads a Popular Classic That Was Neither Assigned Nor Methodically Discussed During Any Stage of His Formal Education

Wherein a Professionally-Trained Historian Reads a Popular Classic That Was Neither Assigned Nor Methodically Discussed During Any Stage of His Formal Education

—————————————————————-

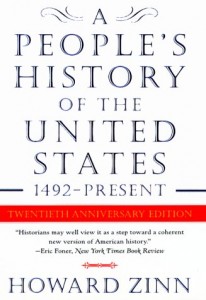

It seems like ages ago—just about six weeks, in fact—since I wrote my first entry on Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States

. Originally I planned weekly reflections on my reading, but other topics came up. And time for typing, for sitting with the book and typing, has been limited.

I won’t recount everything in that first post here, but let me offer, briefly, the following on why I’m reading Zinn: About a week before last Christmas I read Sam Wineburg’s retrospective review and critique of Zinn’s book. That American Educator piece, at a bare minimum, questioned whether Zinn’s book ought to be used in teaching situations. Wineburg asserted that the book could be “educationally dangerous,” and cited several passages therein where contradictory evidence existed–evidence that ought to have changed Zinn’s “interpretive framework.” He added that “Zinn’s power of persuasion,” his charisma, “extinguishes students’ ability to think and speaks directly to their hearts” (p. 33). I found Wineburg’s view compelling for a number of reasons, not the least of which being a personal predisposition to reject radically left and right-wing interpretive frameworks in history (hence my prior opposition to reading Zinn). As such it was easy for me to pass along the review as a “takedown” of Zinn’s work. After being challenged by a colleague about the review, it came up that neither he nor I had read the book (ergo the long subtitle above). Without obligating him, I decided that I should read the book—word for word.

In my first entry, which included pre-reading observations and notes about chapter one, I concluded that chapter one was supremely effective. In the comments to the post Mike O’Connor revealed that he has assigned that chapter when teaching the pre-Civil War U.S. survey. If I ever teach that course again, I’ll do the same. And I’ll also use the chapter, which is relatively short, in any future historiography-type courses. It’s *that* demonstrative.

Now you’re up-to-date. What follows are big picture reflections. I’ve completed 20.5 of 25 chapters (halfway through c-21), and I’m pretty sure that c-20 (based on its sources and tone) concluded the first edition. Given that coverage, I believe most of the observations below will stand even after I complete the book. Next week I’ll provide final reflections and chapter-by-chapter notes.

Big Picture Reflections

1. Quantity v. Quality: This may seem like common sense, but it is worth noting: Chapter length does not always correspond to the importance Zinn sees in a period, or to the importance of that chapter to the reader. For instance, the longest, most-involved chapters in the book are on nineteenth-century slavery (c-9), the Civil War (c-10), the Gilded Age (c-11), the Progressive Era (c-13), World War II (c-16), Vietnam (c-18), Sixties-era Uprisings (c-19), and the Carter-Reagan-Bush 41 years (c-21). Despite lesser length, however, I’d argue that you see a representative portion of Zinn’s passion, personal concerns, and even a small dose of paranoia in his write-up on the 1970s (c-20). In that chapter Zinn’s far left tendencies are on display, but also his deep concern for the manipulation of the masses by Establishment (his term) elites. That chapter goes a long way toward understanding the book’s legacy as a compromised, left-wing tome. Then again, chapter 13 is one of the longest in the book, and is probably the heart of Zinn’s history. It is highly personal and detailed. It deals with a short time frame (1900-1914) and covers a myriad of socialist challenges to both soft progressivism and the lingering ruthless capitalism of the Gilded Age and newfound American imperialism. It is about how people struggled outside the ballot box (p. 345) and how government could not be counted on for social justice (p. 349). This chapter combines all of Zinn’s prominent themes with solid history (using primary and secondary sources).

2. The Standard Historical Narrative?: As the pages progress and the chapters fly by, it becomes abundantly clear that Zinn’s goal is to fight the standard textbook narrative that one probably (hopefully?) learned in high school. He is concerned with how history is taught and even, in at least one case, whether education institutions allow for dissent. On the latter, Zinn asserts that the American education edifice, as it developed in the late nineteenth centurey, was concerned with creating “buffers against trouble” and “obedience to authority.” In this period “history was widely required in the curriculum to foster patriotism” (p. 263). This view underpins his argument about standard textbook history narratives (e.g. “schoolbooks,” “history books given to children”), and he hammers home the fact that A People’s History is different, or revisionist, in many spots using different terms before and after (p. 125, 129, 216, 220, 382, 408).

But Zinn’s encounter condition (i.e. high-school history) is problematic, especially as the twentieth century progresses, and worthy of some reflection. If your education proceeded as did mine in the 1980s, you probably didn’t see what Zinn calls the standard narrative until college—and even then unevenly, or haltingly, if you were not a history minor or major. My only memories of history in high school come from a sophomore world-focused social studies class, and junior-level American history course led by an instructor mostly interested in Native American life (in a way that combined anthropological detail and some history). And my high school didn’t offer AP history. In college I resumed my encounters with history by taking my one required post-Civil War U.S. class. I took another history class during my third year in college, when I took the history of American religion (which was a bad class, really). In recounting my high school and early undergrad encounters with history, I was never really given a “standard textbook narrative” where I actually read from a textbook. I didn’t encounter something like a standard narrative, in fact, until I taught both halves of the survey.

So when does someone encounter “the standard textbook narrative” of American history? Probably late in high school at the earliest, especially in this day and age where math, science, and English competencies are emphasized. Even then we’re talking perhaps 50 percent of the student population, maybe? And how many of them will remember it? Otherwise the encounter will be in college—maybe (if history is required in your institution’s general education/core requirements).

Why attend to this? Because I think it shows that Zinn’s book could be encountered, fruitfully or otherwise, by people anywhere from 15-30 years old. And it could easily (say 50-75 percent of the time) be one’s FIRST encounter with any full-throated account of American history, covering 1492 to 2000 (and beyond). This matters a great deal because it seems clear that Zinn’s book is meant to be a companion to some kind of faulty-but-detailed encounter with all of American history. I’d wager, however, that most read this book with only a middle-school/junior-high level of knowledge of American history.

Praise (limited or otherwise)

a. Even though the sources are dated for chapters 1-20, the book is a remarkable synthesis of revisionist histories produced in the 1960s and 1970s. That synthesis makes it one-stop shopping in relation to the darker moments in U.S. history.

b. The class analysis in the book is thorough and relentless. We may not always clearly see what Zinn is for (socialism), but we know he’s against the capitalist system, inequality, and injustice. There is no overriding sense of progress—a sensibility that infects even the best textbooks produced today, in those I’ve seen anyway. Few readers will have seen his perspective applied continuously over such a long chronological period. But it’s also highly effective over relatively brief periods. Zinn’s take on the Civil War (in c-10), for instance, is particularly striking. The war’s gore makes capitalism, and its attendant inequalities and democratic politics, a life or death proposition. By this chapter one is deeply pondering class solidarity. Indeed, the book fosters class consciousness by exposing how capitalist elites have manipulated politics, race, religion, ethnicity, and gender to distract the masses from seeking justice, economic and otherwise.

c. The prose is accessible. The book moves, and not just because it’s a provocative history of atrocities. This is why someone might say that the book “will fuckin’ knock you on your ass”—if you believe books can do that sort of thing.

d. While most times the presence of extensive block quotes is attributed to the prose of overzealous graduate students, this book gets away with extensive long quotes from primary sources (and occasionally secondary as well). They long snippets are effective, working toward Zinn’s larger narrative goal.

e. Related to those quotes, the book is colorful—“alive” some would say. While the interpretive overlay is clear, it doesn’t smother individuals. The agency of those people is limited, but you see their moments of resistance.

f. While most textbooks today aim for balance, including positive and negative points, that balance falsely softens edges that ought to be sharper. Zinn’s focus on injustice and the oppressed brings together his Marxist class analysis, long quotes, and colorful figures.

g. By the time I reached chapters numbered in the teens, I had developed a begrudging respect for Zinn’s text despite the incessant focus on all that is wrong, the injustices, in American history. I would despair, however, if I thought this was one’s only source for U.S. history. This books must be read alongside other texts. I recommend this not to destroy Zinn’s zeal for injustice, but rather to temper it with the notion that one must see how others in history survived, thrived, and coped within structures they alone could not change.

4. Criticisms: General and Specific

a. Through the first 100 pages or so, this is an extremely depressing book. Read with moderate speed, the book is a blur of violence, oppression, manipulation, and capitalist greed. A sense of fear, paranoia, and despair can envelope the reader. You wonder how you are being manipulated and controlled. You are amazed that America has been built on such a rotten foundation. You wonder why you haven’t been given this information in an upfront manner—why you had to discover it. Yet, the traditional narrative of American history is powerful because you know some of what Zinn is leaving out. What of the positive, high ideals of some of the Founders? You long for the balance that Zinn is denying you. You want a full accounting because surely this isn’t it. Zinn, however, doesn’t really give you a hint of the positives of the standard narrative. The reader then grows frustrated because this isn’t a fully true accounting of America’s past.

b. Through its constant, one-sided criticism of government action (i.e. solidarity via government), the book undermines—thoroughly—one’s faith in the democratic process. The only alternatives seem to be anarchy or revolution. Is this healthy for young people? Does the book’s “realism” on this undermine hope in peaceful change?

c. While the chapter on World War II (C-16) can be praised for its alternate viewing of the so-called “Good War” (to Zinn it wasn’t at all a humanitarian effort), it is also the most presentist in its tone of judgment. Just because the U.S. and Germany were similar in context and matters of race, class, and gender doesn’t mean that, in the biggest things (e.g. Holocaust violence, anti-Semitism) the were similar enough to be lumped. This is a challenging chapter (Zinn’s goal), but it also feels the most skewed. And this was the chapter with which Wineburg levied some poignant charges about Zinn’s lack of complexity, factual errors, and narrow sources.

d. Despite being a book about “the people,” there are times when those people are viewed from high altitudes—as groups with little human agency. While the book is encyclopedic in its cataloging of injustices, we get no on-the-ground sense of the culture of those people—their intimate needs, wants, desires, pastimes, and uplift. Its labor, war, and politics all the time.

e. In Zinn’s discussion of capitalism during and after World War II, he refers to “capitalism rejuvenated” (p. 425) as opposed to the creation of what historians like Eric Hobsbawm called a “mixed economy.” Hobsbawm argues, in Age of Extremes, that this (not so) subtle thing changes one’s perspective on the “golden age” of economic growth that occurred after the war. Western leaders were forced to tamp down capitalist greed for the sake of social stability. But, reading Zinn, one sees the era as a kind of new Gilded Age. This causes me to think that Zinn treats capitalism as a homogeneous category of analysis. No nuance is possible nor desired.

f. In this chapter (16), Zinn also begins to refer to “the Establishment” or “the system.” This nomenclature occurs for the rest of the book (pp. 429, 448, 514, 541, 549, 550, 559, 565, etc.). In this chapter it is used to refer to the early 1950s consensus. But, because it’s cliche, it betrays Zinn as a Sixties activist. From this point forward Zinn’s narrative feels like it’s written by an aging Baby Boomer than by a historian with a message composed of clear themes. It’s the kind of language that enrages conservatives and right-of-center moderates.

g. Not to belabor chapter 16, but herein Zinn also goes into excruciating detail about the Rosenberg case

. Frankly, the detail slows the narrative greatly, interrupted his prior flow of larger injustices to the working and middle classes. Indeed, that case, in its polling of the people, shows how focusing on “the people” can show how their desires are, at times, dark and uninformed (e.g. polling never favored the Rosenbergs). Sometimes everyone seems to want the wrong thing, the thing that is both unjust and untrue.

h. The Gulf of Tonkin incident, in chapter 18, is relayed as “fake” and conspiratorially constructed (p. 476). But more than enough evidence points to confusion and misunderstanding being plausible explanations. Zinn’s hindsight and paranoia sometimes undermine the effectiveness of a honest portrayal of complexity. He could have used that complexity to make arguments about state caution and hubris rather than conspiracy.

i. Zinn’s narrative about resistance to the Vietnam war and draft evasion among lower socioeconomic classes is muddled (pp. 491-492). He tries to argue that anti-war protest was not just the domain of the privileged. True enough. But he needed more evidence about working-class resistance in the face of now-trumped up narratives of Sixties-era working-class patriotism (the kind utilized effectively by Nixon). This is a chapter where more recent scholarship could help Zinn.

j. Chapter 16, on World War II and the Cold War, is the last chapter where historians are mentioned in the text. So, from the mid-1950s and onward, it feels like Zinn alone with primary resources. Since the postwar era is in Zinn’s comfort zone due to his prior work [Postwar America: 1945-1971 (1973), SNCC: The New Abolitionists (1964), Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal (1967)], this is fine. But there was no reason to stop the engagement with other scholars. If you look at his Bibliography for chapters after sixteen, other secondary sources are indeed listed. This matters because his in-text engagement with historians on events prior to the mid-1950s adds an air of legitimacy to the earlier narrative. He should’ve kept engaging the work of other historians on post-early Cold War topics. And because of the successive updates of the book, I’m with Wineburg in that this is problem. There have been so many good books published on the post-war era since the 1980s that it feels like Zinn simply gets lazy as the we get closer to the present—which adds to a feel of presentism and subjectivity.

k. In his chapter on 1960s and 1970s “surprises”—meaning the public agitation by women, prisoners, and Native Americans—Zinn makes a contradictory statement about how Catholicism functioned in the public sphere. Near the end of the chapter, Zinn states that the Catholic Church “had for so long been a bulwark of conservatism, tied to racism, jingoism, war” (p. 538). But in the prior chapter (18, on Vietnam), Zinn very prominently discusses the fact that “the antiwar movement, early in its growth, found a strange,new constituency: priests and nuns of the Catholic Church” (p. 488). He spends several pages thereafter discussing the activities of Philip and Daniel Berrigan, the “Catonsville Nine,” Mary Moylan, and heathily attended anti-war activities at Boston College and Newton College of the Sacred Heart. In no part of that chapter does Zinn argue that these Catholics were mere outliers, though he does say that these activists Catholics worked against “the traditional conservatism of the Catholic community” (p. 490). At the very least, Zinn’s views of Catholic history during the 1960s and 1970s are a bit muddled.

l. I mentioned above the importance of chapter 20 (focused on the 1970s) in terms of understanding Zinn’s legacy to the common consumer of history (and to today’s conservatives). This was probably the conclusion to the original edition of the book. This chapter, taken by itself, is the most subjective and leftist-feeling in the book. It even enters the realm of paranoia, acting as a kind of left-eye photo-negative of right-wing conspiratorial theories about midcentury liberals. When I was growing up, my hyper-conservative, John Birch sympathizing grandfather talked regularly about our government being controlled by the Trilateral Commission, Rockefeller money, the Bilderberg Group, the Masons, and various other secretive collaborations. Using the writings of Samuel Huntington, Zinn himself veers into this territory from a left-wing perspective. To Zinn, those same groups manipulated the American Establishment (the system) to channel “excess for democracy” toward capitalist ends (pp. 559-461). Zinn’s concern for the rise of globalization and multinationals sounds exactly like my grandfather, shortly before his death in 1994, railing against NAFTA, President Clinton, and the United Nations. In this chapter Zinn refers to Congress as a “flock of sheep” (much like Tea Party folks today), and advocates that our system be purged of “rascals” (e.g. my grandfather always advocated for throwing the rascals out).

————————————————

This is it for today (understatement). I expect to finish A People’s History this weekend. If so, next week I will provide my final thoughts and brief chapter notes (e.g. chrono, thesis, themes, topics for each chapter). – TL

18 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Very interesting post, Tim. I think the point you made about the book’s status as a counter-narrative is very important. Much of the historiography produced by the New Left and its heirs took this form. And that made a lot of sense in the 1960s and 1970s, when most college-age (and older) Americans might reasonably have been expected to have received the standard narrative in high school. Since as far back as the 1980s, and certainly today, that was simply no longer the case, which I think makes the entire counternarrative enterprise problematic, even if one is untroubled by the issue of balance. I once served as a TA in the early 1990s for a professor who built a lecture course around similar counternarrative lines and the students seemed, in various ways, confused by the course. As we learned at last summer’s RNC, arguing with an empty chair never makes a speaker look good.

Thanks for the comment, Ben. The counter-narrative status of the book suggests, to me in relation to today, that the book could be taught alongside a middle-of-the-road type textbook (say Faragher et al’s *Out of Many*). However, I would not simply teach APHUS with a right-wing text because, as Wineburg notes in his critical review, that combination of content results in a student not being exposed to the nuance and complexity that is indeed available in some survey texts. – TL

Today’s standard survey texts are also post-Zinn; they have, themselves, incorporated a lot of the historiography that was produced by the New Left. They don’t (re)produce the narrative against which Zinn wrote.

Today’s standard survey texts are also post-Zinn

Aye, Ben. That “we” [whoever “we” is] screwed the red man and the black man even worse is no secret to the merest American child; it might be the takeaway on our history for the majority of our youts.

I suppose this is good; truth hurts. OTOH, turning our schools into the Fidel Castro Institute for Why America Sucks* may already be undoing us.

“We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and then bid the geldings to be fruitful.”

— C.S. Lewis

Some skepticism is healthy. Cynicism, not so much. One’s a tonic, the other a disease.

___________

*A Richard Jeni line. RIP. Dude was funny.

Thanks for this Tim. It sounds, and I may be reading too much into your review, that Zinn is giving the ‘secret’ history of the US that ‘they’ don’t want you to know. A little bit like you’d hear in an infomercial. Does he give a statement about his intent or thesis in an introduction?

Paul: Chapter one lays out, very publicly, Zinn’s approach. I don’t think it’s fair to calls this a “secret history” due to the Nostradamus-like connotation of that phrase. I think it’s clear to the reader, from the start, that Zinn is surveying publicly available (and now dated if still relevant) scholarship that counters the old standard history narrative. So it’s not infomercial-$19.95 type history (it only feels that way in chapter 20, at the very end). Zinn’s classic is just a long history of America given from the point of view of the oppressed, marginalized, and downtrodden. – TL

Tim, thanks for this thorough review. Sad to say, I have never read Zinn, but now I feel like both a.) I should; and b.) I have a better idea of what to expect when I do. What is interesting is that at multiple times in the last few years I have had students come up to me on the first day of class and ask if my teaching is influenced by Zinn’s book–and I usually cannot tell if they think this would be a good thing or not. (Maybe a teacher in high school told them to ask this? I don’t know.) What I recall telling these students is this: I am not influenced specifically by Zinn’s book, but because I took my historical training when and where I did, my teaching is undoubtedly shaped by counter-narratives such as his. After all, I think that very few of us with history PhDs earned in the last 30 years or so teach the “standard narrative” that existed before the 1960s/1970s.

I think that some other readers of Zinn’s APHUS (is that a funny initialism?) see it as becoming a member of a club—you’re initiated. And because the book is well-known and engaging, they’re probably shocked and disappointed when they learn a professional historian has not read it.

On teaching either the 1960s/1970s standard narrative or Zinn’s counternarrative, I don’t think we do either. This follows a bit on Ben’s comment above, but having taught a U.S. survey with a respectable recent text (Faragher et al’s *Out of Many*), I can testify that while that book includes some of Zinn’s points, it by no means included all of them. There is still something to be gained from Zinn’s counternarrative—even if the new narratives graft some of his points. – TL

BTW: Happy Valentine’s Day, dear readers! 🙂

Tim: Most states now require at least one year of US history. And most high school textbooks, which have been surveyed by James Loewen as recently as 2007 in the second and revised edition of “Lie My teacher Told Me,” still give a standard narrative of US history about unbending progress, etc. Some new figures have been added to reflect multicultural pressures, but the trajectory of the traditional narrative remains. With this as context, I think assigning Zinn as a counter-narrative in a high school classroom is a great idea. In fact, I did it when I taught high school US history. As you make clear, Tim, it’s an engaging read–certainly more engaging than textbooks. Many of my students loved it. Getting students to love reading a thick history book is a win. Period.

Unlike Wineberg, I don’t worry about Zinn being widely read because very few Americans learn or think about history with any complexity–certainly nothing approaching the complexity we were all taught in graduate school. In such a context, Zinn’s book, admittedly not very complex, is a net positive for two reasons.

1) I’d honestly people rather have his un-complex narrative than the standard un-complex one (but I’m an unreconstructed lefty, and realize my position on this is shaped by my politics).

2) Zinn can be a gateway drug to history. How do I know? It happened to me. “A People’s History” was the first history book I enjoyed reading.

Thanks for this post–I’ve enjoyed thinking about Zinn again ,after all these years, through your eyes.

Thanks for the praise, Andrew. I need to read Loewen’s book someday—can’t believe I haven’t.

And I agree with you completely on the point about getting students—at any level—to read thick history books. A win indeed.

Do you think, Andrew, that your college instructors, high school teachers, or parents influenced you to be open to leftist history? I ask because I was closed to leftist perspectives due to family reasons. It’s amazing how long the momentum of one’s childhood and young adulthood carries on—even when you’re far away intellectually and emotionally from where you were formally. I’m sure that momentum prevented me from simply grabbing the book and reading it even ten years ago.

What a refreshing review, Tim. I’ve always been a big Zinn fan. I’d probably say he is my favorite deceased historian. I first cracked “A People’s History” open when I was about 13 years old. But at that age most of the polemical nature of the book was lost on me. Around my sophomore year of college (~5 years ago), I decided to read his autobiography. This was mostly because “A People’s History” is gigantic. I actually read a number of his other works before “A People’s History” as well (“The Case for Socialism” specifically comes to mind).

Needless to say, Zinn inspired me tremendously. But I quickly learned to keep that to myself as I noticed the historically-inclined folks in academia don’t seem to much respect him. I have since read “A People’s History” but with a more discerning eye than I would have not knowing his unfortunate reputation. I thought it was a fantastic book and indeed should be required reading for history students. As you mention, the prose is very accessible. And for students, that is often the most crucial element.

All of this is an overlong way of saying thank god others feel the same way.

I enjoyed the review. Thanks!

Mike,

Thanks in turn for the comment.

The story of your encounters with Zinn seem most unusual. So, are you a historian, in the academy or otherwise? How has Zinn influenced your reading of histories?

– TL

Tim,

I am actually a graduate student in Dr. Hartman’s Culture Wars seminar at ISU. He has linked us to the blog a few times, so I checked it out. You guys do fantastic work.

Unfortunately (fortunately?), I have always been a cynical contrarian. This I attribute mostly to my childhood where I experienced a lot of the class and religious issues Zinn describes. And as a teenager I had a number of quite older friends that suggested Zinn to me because of my tendencies. So that is how Zinn came into my purview.

As for how it influences my reading, well, I can only say that it diminishes most other works. Zinn’s book is so easy to read, it makes everything else read like a convoluted federal statute or something akin. More importantly, it has caused my reading of other histories to be much more critical than they may otherwise have been. I do attempt to challenge my personal views with what I read, but nothing has ever been able to do that like Zinn did years ago.

The thing I most respect about Zinn–outside of his intellectual acuity–is that he practiced what he preached. He railed against war, but his perspective was justified as a veteran. He fought for civil rights in the 60s, he protested Vietnam, he worked in the shipyards and experienced labor strife, etc etc. He is uniquely qualified as an alternative historian.

Tim: Yes, I grew up in a very liberal home. Both of my parents were public high school teachers and lifelong pro-union Democrats. A few months after I was born, they proudly voted for McGovern, which should give you an indication of their political commitments since even many Democrats did not pull that lever. I also had a few good history teachers. My junior high school history teacher was, when I think about it in retrospect, an Italian leftist who made me very sympathetic to Sacco and Vanzetti. Which is all to say that I was primed for Zinn when I first read “A People’s History” in my late teens.

In my early twenties, while I was studying to be a teacher, my methods professor was a churlish socialist who turned me on to all kinds of other leftist writers, and Zinn’s other works, especially his inspiring autobiography, “You Can’ Be Neutral on a Moving Train.” By then I was a voracious reader of revisionist history–and I credit, in part, Zinn for this. As such, Zinn must get some credit (or blame!) for me becoming a historian. For all these reasons, I have little patience with the Wineberg critique.

With respect to your answer to my question, and my own background, check out this quote from Zinn that I discovered via Zinn’s Wikipedia entry:

“We were not born critical of existing society. There was a moment in our lives (or a month, or a year) when certain facts appeared before us, startled us, and then caused us to question beliefs that were strongly fixed in our consciousness – embedded there by years of family prejudices, orthodox schooling, imbibing of newspapers, radio, and television. This would seem to lead to a simple conclusion: that we all have an enormous responsibility to bring to the attention of others information they do not have, which has the potential of causing them to rethink long-held ideas.” — Source: “Changing Minds, One at a Time” by Howard Zinn, Published in the March 2005 issue of The Progressive.

ok, but, and i say this as someone who believes himself to be broadly sympathetic to zinn and his project, is this citation really a plausible description of how people are and how they relate to their worlds? i think not.

Also, kudos to you for being born of parents who looked at the world with reflective critical eyes. I see lots of critical out there, but not much deep reflection informing that criticism. – TL