In my History of the Modern World course, I have begun to address the evolution of law and political rights in the decades before the revolutions in the Americas and France. As part of a lecture on Locke and Rousseau, I show a clip from Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons

. While historically anachronistic, the film does have an excellent exchange over how to apply the rule of law. In the scene, Thomas More confronts his family when they demand he arrest Richard Rich on the very reasonable suspicion that Rich intends to do imminent harm to Moore. You all know the story, here is the scene: Devil Benefit of Law

What makes the scene so interesting is that students often don’t quite know which aspect to focus on–is it giving the Devil the benefit of law; or More’s distinction between “man’s laws” and “God’s laws”; or the obvious respect More has in this scene for the idea of law?

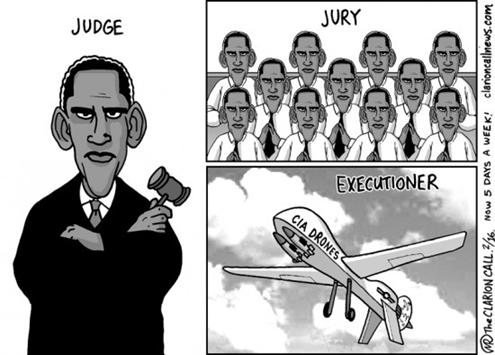

The conversation in my class perhaps inevitably led to addressing the Senate’s confirmation hearing of John Brennan as President Obama’s director of the CIA. When reading about Brennan’s case for the Obama Administration’s drone policy, I asked the students to consider how the questions raised in the film clip might lead them to ask questions about the use of drones, especially in light of the killing of an American citizen without due process. We wondered, collectively, whether Brennan had become somewhat like William Roper, Moore’s son-in-law in the scene, who would cut down every law in England to get after the Devil. To which Moore retorts that cutting down the laws for such “noble” intentions will, in the long run, eliminate protection for everyone–no matter how noble.

That line of reasoning echoes Tom Engelhardt’s essay at HNN

. In his conclusion and nearly in exasperation, Engelhardt argues:

“The drone strikes, after all, are perfectly ‘legal.’ How do we know? Because the administration which produced that 50-page document (and similar memos) assures us that it’s so, even if they don’t care to fully reveal their reasoning, and because, truth be told, on such matters they can do whatever they want to do. It’s legal because they’ve increasingly become the ones who define legality.”

“It would, of course, be illegal for Canadians, Pakistanis, or Iranians to fly missile-armed drones over Minneapolis or New York, no less take out their versions of bad guys in the process. That would, among other things, be a breach of American sovereignty. The U.S. can, however, do more or less what it wants when and where it wants. The reason: it has established, to the satisfaction of our national security managers — and they have the secret legal documents (written by themselves) to prove it — that U.S. drones can cross national boundaries just about anywhere if the bad guys are, in their opinion, bad enough. And that’s ‘the law’!”

In the end, my students and I wondered if Brennan had become our contemporary Roper, claiming to act for the benefit of the people by using “God’s laws” (or in this case, a civil religious version of them) to get after our modern version of the Devil. Not surprisingly the students wanted to know where our Thomas Moore was. I suggested that “he” exists in the Senate hearings and the work being done by news outlets such as the Washington Post.

I am interested to learn who else and where else we should look for analysis of the legal implications of the drone policy and perhaps how to contextualize the debate over it.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Very interesting (and important) post, Ray. Two thoughts came immediately to my mind:

1) In our Constitutional system, Congress is, indeed, the designated Thomas More. The problem is that Congress, at best, fitfully asserts its powers over warmaking, and even then it does so with little success. Scott Lemieux has an interesting, new piece up at the American Prospect that explores why. Lemieux basically suggests that Madison (e.g. in Federalist 51) assumed that Congress would jealously guard its powers and would thus not allow the President to act unilaterally in apparent violation of the Constitution’s resting war powers with Congress. But, in fact, Lemieux argues, it is almost never worthwhile for Congress to take responsibility for war, so they are happy to let Presidents take the lead. Two take-home points here: a) Congress is only very loosely Thomas More, as its role in our politics is based on its (presumed) self-interest in moderating Presidential action, not in a virtuous devotion to law (human, natural, or divine); b) at least in this regard, our Constitutional system is profoundly broken.

2) What is the relative merit — moral, political, and otherwise — of the Administration’s argument (which I think Englehardt basically has correct) that legality is based on objective facts that are only known and only knowable to the Executive Branch vs. the argument one associates with the Melian Dialogue, that legality simply lies with the will of the strong? At times I think the latter at least has the advantage of honesty (and manages to more clearly distinguish between US drone killings and hypothetical Iranian drone killings of US citizens). On the other hand, few (I hope) would want our government to simply embrace the principle that justice consists of the strong doing as they will and the weak suffering as they must (though the Bush administration, at times, seemed to crawl some distance in this direction rhetorically). Might the sheer amorality of such a Thrasymachan view of justice recommend the circular nonsense of the Administration’s claims as a kind of noble lie? I do wonder what the meetings that led to the administration’s position looked like: what was the admixture of Machiavellian realism, empty legalism, and simple moral laziness?

One other thought on a side issue: a number of those criticizing the drone program have argued that we shouldn’t much focus on the fact that American citizens are being targeted. The critics argue that, for both legal and moral purposes, it shouldn’t make any difference whether those being killed without due process are U.S. citizens or not. While I see the legal and moral points here, I think that the willingness of the executive branch to explicitly target U.S. citizens remains an important fact, worthy of special criticism. Even if the distinction between U.S. and foreign citizens as drone targets has little moral or legal significance, it has social and practical significance. Rightly or wrongly, our government has frequently treated foreign nationals differently than it has treated its own citizens…and when it has mistreated its own citizens, the denial, restriction, or minimization of their very citizenship has often been a precondition for that mistreatment (e.g. American Indians, African Americans (in slavery and under Jim Crow), convicts, etc.). Moreover, the U.S. government simply has easier access to U.S. citizens than to foreign nationals. So it does make a practical difference that the government is explicitly claiming the right to kill its own citizens without due process.

It’s interesting how this debate parallels the debate raging/simmering over gun control. The “devil” manifests in many ways or maybe the same way?

I suspect the drone policy stems from the logic illustrated by this quote from Oliver Wendall Holmes, “I think that the sacredness of life is a purely municipal ideal of no validity outside the jurisdiction.”

It seems as though American foreign policy is predicated on this notion and applied arbitrarily without legal clarity. John Yoo’s defense of the Bush administrations actions is a perfect example. http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2011/12/my-debate-with-john-yoo-who-misunderstands-the-constitution/249598/

the sovereign decides on the state of exception? not so?

honest question: are there legal consequences to the fact that these are killings undertaken by unmanned aircraft? or is it just somehow scarier to talk about ‘drones’ than other kinds of targeted assassinations? my understanding is that drones are preferable because they allow rapid, long-distance, and relatively inexpensive strikes without risking the lives of american military personnel–which no doubt is thought to be bad because it lowers the potential political cost of targeted killings, and therefore encourages them. but are there other considerations?

Seems to me that Englehardt muffs the question of mutual drone legality: Yes, it would be illegal for Pakistan or Brazil to fly drones over US airspace, according to US law, but it might be entirely legal as a state act according to Pakistani or Brazilian law. Similarly, while the US government may consider drone patrols, surveillance and strikes as legal acts, they may still be violating the law of the countries in which the acts take place. Legality is not a simple binary condition.

I great appreciate the responses, especially from Ben, as my students will now have little extra work for next week! I accept that law is not an either or proposition, as Jonathan points out, especially when systems of laws interact. I remain unsure about the appeal to the laws of war that seem to be invoked by the administration AND the critics of it when coming to terms with the strategy and tactics. Clearly, as Eric suggests, drones are far from the worse kind of weapon used in war and as the administration consistently argues, no Americans are in harms way when these actions are taken (except those targeted for death, of course). But I continue to wonder how to characterize the drone policy–does the complex web of legality lead the discussions about the moral implications of it; or does the need to hunt down terror suspects without endangering Americans allow creative readings of a tangled, but still crucial, set of laws?

I do think those obsessed by the “war on terror” will tend to exploit the law solely toward their understanding of the nature and necessity of that war such that virtually any means become suitable and justifiable in light of the ends perceived as intrinsic to such a war (and I think the logic of ‘legal realism’ and ‘critical legal studies’ attest to that possibility or fact). On the other hand, the laws of war, both the jus ad bellum aspect which presumably would be associated with any attempt to justify the “war on terror,” and the jus in bello aspect that motivates international humanitarian law (IHL), involve moral concerns and considerations, both as the original motivating force behind the laws of war and as essential to its various principles (e.g., think of Grotius and the natural law tradition from whence this comes). Now of course one can always re-examine the moral scope and content of these principles (as the philosopher Larry May has done so well), but we should not assume such law is necessarily in conflict with morality if or when it speaks to “strategy and tactics.” If one is a pacifist, then of course the “laws of war” will be morally troubling from the start, yet I think even a pacifist can appreciate the (minimal) moral value of such laws for those who don’t subscribe to pacifist beliefs and values. After all, when it comes to international law, the recognition by states of the importance and relevance of IHL since WW II represents considerable moral and legal progress, even if it falls well short of cherished moral intuitions or other moral beliefs and concerns we may possess.