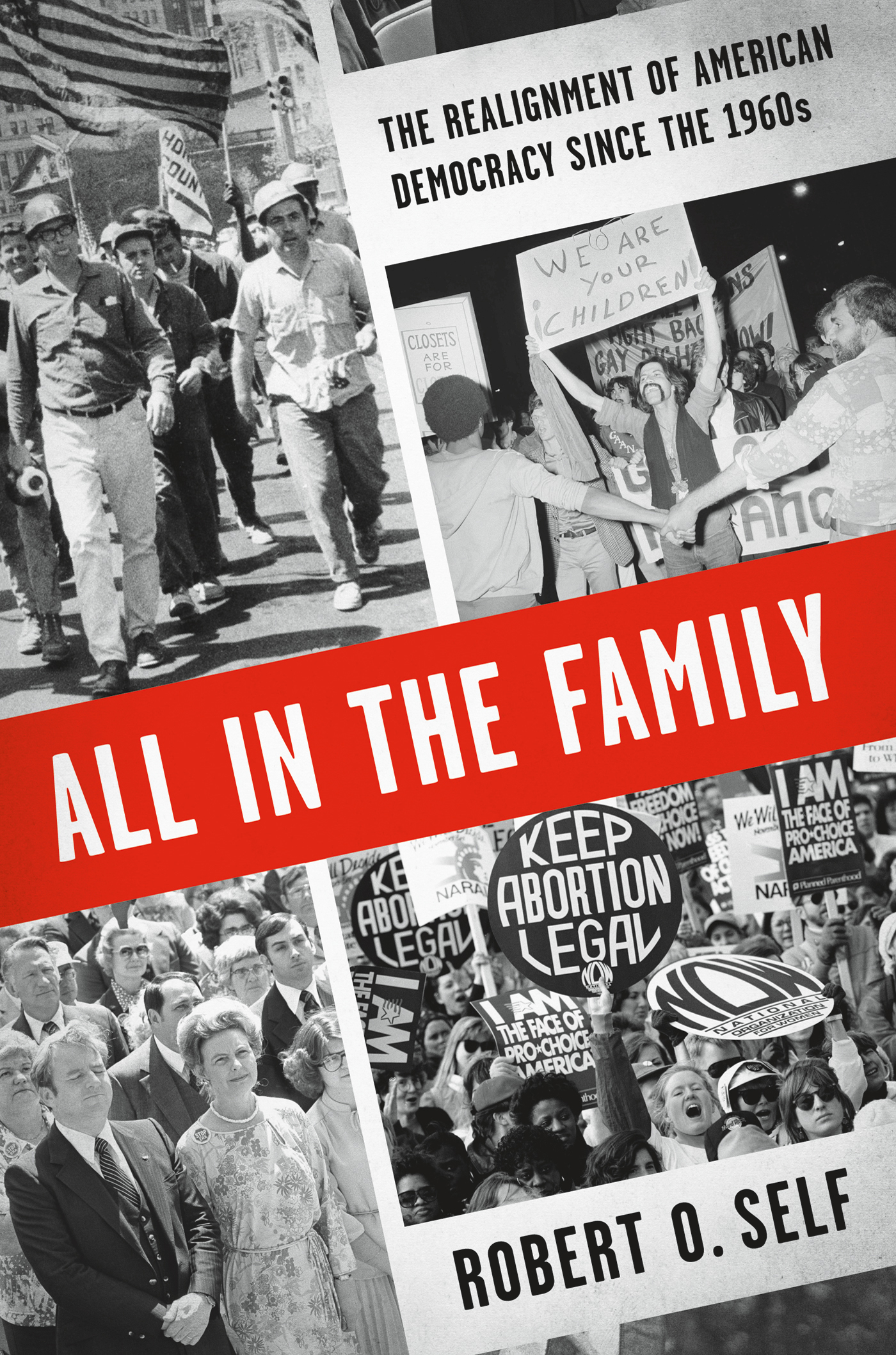

The following is Robert O. Self’s response to Christopher Shannon’s two posts regarding Self’s latest book, All In the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy Since the 1960s. At the new S-USIH blog, this essay reminds us what has been the best about the origins of the blog and, going forward, the kind of intellectual forum we hope to provide and encourage. Thanks to Self, Shannon, and all those who have read and commented on their different posts. Here is a page with the earlier posts.

I would like to thank the moderators of the U.S. Intellectual History blog for inviting me to respond to Christopher Shannon’s recent post regarding my new book, All in the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy Since the 1960s. I would also like to extend my thanks to Prof. Shannon for taking the book seriously and engaging with its assumptions and arguments. In the long run, it is more rewarding to read a sustained critique than a prolonged acclamation.

Let me add that while an extensive discussion of these issues has already taken place in the comment section of the blog, I am replying only to Prof. Shannon’s original post.

I

Allow me to get some important points out of the way quickly. I acknowledge that my own philosophical proclivities incline me to sympathize more with the architects of what Shannon calls the “progressive diversification model of family life” than with their opponents. It would be both disingenuous and foolish of me to claim otherwise. Yet that does not relieve me of the responsibility of the historian. Shannon’s sleight of hand, unintentional though it may be, might lead the casual reader to think this is a book of unadulterated advocacy. It is not.

For instance, Shannon writes of me that “he believes that [now quoting my book] ‘women and men, male and female, sex and sexuality, are in the end social constructs . . .” In fact, what I wrote in the book is the following: “They argued that women and men, male and female, sex and sexuality, are in the end social constructs . . .” The “they” in that sentence refers to those who leveled the most ardent political and cultural critiques of breadwinner liberalism in the 1960s and 1970s. The “they” are among the many subjects of my inquiry. They are historical actors.

Much of the book is devoted to trying to understand what happened when activists who believed that gender is a social construct faced the political realities of attempting to bring into being a world based on that very idea. My book argues, in great detail, that they succeeded and failed in equal measure. As a historian, I may also have some faith that gender is a social construct, but I imagine there are better ways to prove that point that Shannon’s leaving out two critical words in a textual sequence composed of sixty. Moreover, he neglects to cite the sentence immediately following the end of the quoted section. I write: “But it is not easy to bring that social order into being.”

What I set up here is not a moral argument that “progressive” models of family life are inherently better than traditional ones. Rather, I set up a historical, and narrative, tension: between the beliefs and aims of activists and the realities of politics. The tension between what they wished to accomplish and what they could accomplish. This tension drives much of the book. The reasons why “it is not easy to bring that social order into being” are the primary subject of All in the Family.

Second, Shannon argues that I write the story as a “Manichean struggle” between good guys and bad guys. I leave it to other readers to judge whether this accusation is true. I will simply say that “Manichean” implies a moral distinction I never make in the book. A close reader of All in the Family will notice that I fault liberals for their overly optimistic view of market rights and at other times fault radicals for their overly utopian dreams of a world free of patriarchy and their disdain for the basic fight for rights that others saw as the essential, core struggle of the era. The “good guys” in my story are not the uncomplicated bearers of a superior morality. They are deeply flawed, often blind to the outcomes and implications of their politics, and always in conflict with one another. These are not the ingredients of a truly “Manichean” struggle, if we are to take that descriptor seriously.

Finally, in an effort to demonstrate that I make the market a hero in the book, Shannon again fails to include the entirety of a quoted passage and ignores other relevant passages – indeed, long sections of whole chapters – that contradict his point. He argues that I put forth the market as an appealing alternative to marriage “as the vehicle for women’s economic security and public standing.” In fact, that entire sentence reads as follows: “It [breadwinner liberalism] posited marriage, not the marketplace, as the vehicle for women’s economic security and public standing.” I, the author, am not stating that the marketplace is better than marriage. Rather, I am making the analytical observation that breadwinner liberalism, as an ideology, posited marriage, not the market, as the basic source of women’s security and public standing. This would hardly seem to be a controversial statement.

II

But when it comes to the market, I offer not a celebration but rather a sequence of measured appraisals. Shannon ignores these entirely. For instance, in the chapter on women and work I observe (based on the advice and fine scholarship of Dorothy Sue Cobble and Linda Gordon) that for many working-class women, the market was hardly a welcome realm. Indeed, many sought not market freedom but two things: market protections and even an escape from the market itself into domesticity. I have written long sections about how the middle-class vision of feminism failed to resonate with many working-class women because for the latter the market was a place of low wages, arrogant bosses, limited mobility, and exhausting labor. Plenty of women, then and now, preferred marriage to the market. What Shannon misses, or simply disagrees with enough to ignore, is the long-standing feminist critique: so long as marriage is understood as women’s primary cultural and economic destiny, the market will always be able to exploit them fully. This is hardly a celebration of the market.

If the book is a celebration of anything, it is of people’s remarkable, if rarely rewarded, faith that they can bring into being a new world, a new “public good.” And here we can leave behind small points of Shannon’s faithfulness to my text and address larger historical questions. Shannon rightly notes that I describe breadwinner liberalism as a kind of public culture that distributed positive rights, through government, in exchange for living according to certain behavioral (cultural) norms. This public culture came unraveled in the 1960s and 1970s under a massive assault from all corners: social movements on the left, the market, and the political right. The implication, which he makes clear later in the review, is that I endorse what he presumes arose in the place of breadwinner liberalism: a market-based, consumer-choice model of family diversification and the end of the public good.

That is a misreading of both my argument and the historical record. Virtually all of the activists on the liberal-left about whom I write did not seek an obliteration of the public good. They sought a redefinition of it. They sought not an obliteration of the duty to live according to commonly held values. They sought a redefinition of what those commonly held values were. They sought a replacement for breadwinner liberalism: one that was kinder and more advantageous to women’s freedom and basic humanity; one that was accepting of sexual difference; one that forbade rape and sexual harassment (and, for many, an end to racism). They said things like: if I am a woman and I go to work, I have the right not to be sexually propositioned and harassed in the workplace. That is not an obliteration of the common good in favor of some abstract “consumer pluralism.” Rather, it’s an articulation of a common set of values and a “reciprocal relation” of duty. Your duty is to live up to a set of values in which women are empowered and protected as human beings, workers, sisters, mothers, as people (as they used to say).

Or take the case of sexual freedom, a topic to which I devote one entire chapter and large portions of other chapters. One can hardly find in these discussions an uncomplicated embrace of “consumer pluralism.” I discuss at length, for instance, how anti-pornography feminists entirely distrusted the market, so much so that one wing of the movement came quite close to endorsing censorship. Very few women in the movements about which I write trusted the market when it came to questions of sex. After all, they had to invent the women’s health movement, because the existing medical markets (and publishing markets) all but refused to acknowledge core questions of women’s sexual and reproductive health. As I argue in the book, regarding sex, feminists made a basic demand of any public to which they belonged: “cultural recognition and legal protection of women’s consent.” They sought not an obliteration of the public good but a redefinition of it.

The most self-conscious and progressive of them demanded that the racist patriarchal public culture of the nation be replaced with a non-racist and non-sexist one. Did they succeed? Yes and no. But how they succeeded and where they failed is the essence of the story. How they succeeded and where they failed tells us a great deal about the distance the nation traveled in the fifty years recounted in the book, and it tells us a great deal too, about the basic elements of American democracy, law, and political cultures.

There were those, to be sure, who pushed past any notion of the public good to embrace radical individualism. But I am always careful to identify and contextualize their quests. For instance, at the heart of gay politics there was always a fierce debate – that continues to this day – about whether gay life meant a commitment to absolute sexual freedom or whether it meant something rather more mundane: something, well, like marriage. That debate is historical. It’s there in the activist circles, and it’s chronicled extensively in the book. Again, I will allow readers to make up their own minds about where I come down in evaluating those debates. But to suggest that I simply and blithely endorse consumer pluralism as progress seems to me a basic misreading of my own argument and the complexities of the struggles in which people of these decades were so deeply engaged.

In fact, what most interests me is precisely the conundrums they encountered. Activists started out believing that bringing a new world into being, based on new values and public commitments, was possible. And what they ended up discovering is that in mobilizing government to make that new world real, they actually faced narrowed choices. New negative rights of freedom worked well for people who already had access and standing in the market and other publics. For those who did not, “freedom” was not enough. It was much more difficult to bring into being a new public culture of feminist and anti-sexist values and duties than they imagined. Why? The book has a complicated answer: because a powerful movement arose to oppose them and

because of the nature of American law and institutions and the fact that those who were most able to affect change were largely middle-class and white and thus could benefit from negative rights (“freedom”).

III

Finally, let me address what I consider the heart of Shannon’s argument. And here I will make more concessions to his critique than I have thus far. There are two parts to it, as I see it.

First, Shannon suggests that I don’t do enough to recognize how the left-liberals’ demands for positive rights might have been corrosive to public culture. That’s probably true. There were certainly moments in the story I tell in which activists and their allies developed an absurd over-confidence in their capacity, through government, to remake the world. The urgency of their demands and their belief that the world in which they wanted to live required new rights and new government powers at times did not make room for a slow process of evolution. They wanted an old world destroyed and new one born. Thus it may be true that in my analysis I do not often enough point to the ways that their very urgency and idealism blinded them to how their demands might damage the public culture of the nation.

That’s because I’m more interested in a different issue. And here I’ll defend my perspective. I’m more interested in why what they so ardently believed was right could not be made real. Let’s take a simple example, one with which I end the first chapter. This is the fight over construction trade jobs between black and white men in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Could black activists have said the following: We are breadwinners, we have families to support and we wish to hold breadwinner jobs. But we see that you (men of various white ethnicities) already have them. Therefore, we’ll be patient and live up to the cultural norms of our society. We’ll support our families as best we can, work hard, and earn these jobs, which one day we are confident you, or someone like you, will give us. Could they have said that? Sure. Many did. For decades since Reconstruction.

But in the 1960s and early 1970s, a good many black men said something else. They demanded their fair shot at those jobs, right then. They also demanded that businesses – and eventually the government – take “affirmative action” in looking for and employing qualified black workers. They pointed out that in many major northern cities, black men were a majority or a near majority of the working-age population. But they held less than 5% (much less in most cases) of the best blue-collar jobs in those cities. And this was no accident. They had been barred from those jobs, barred from those unions.

Because I come out of urban history, in which the inclusions and exclusions of any idea of the “public good” are so stark, I have a difficult time sitting in judgment of those black workers for corroding public culture. As they saw it, quite rightly in most respects, that public culture had never and would never include them. Indeed, I find the entire situation, as I write in the book, so entirely overdetermined that it’s difficult to find anything historically interesting to say about it any longer. They were in an impossible position. But neither does that mean I condemn all white workers as racist. They, too, were in a situation not entirely of their own making (at least many of them). Most of them were one generation removed from poverty. Breadwinner liberalism had worked for them. They did not understand how their holding a job meant that others could not. And they defended their jobs against black demands as vehemently as black protestors pushed for access to those jobs.

If Shannon can show me how the public culture of breadwinner liberalism could have resolved that crisis, I’d gladly listen. I don’t think it could have. And thus it began to come unraveled. It’s stories like these that make up the majority of the book: episodes that highlight the failure of breadwinner liberalism, as it had been understood by two generations of Americans, to deal with the multiple crises of the 1960s and 1970s, and the way in which as a result it came entirely unglued.

A final point here. One could argue that I have given the standard left-liberal answer. I don’t blame black workers (or feminists or lesbians and gay men) for their corrosive effect on public culture and the “common good” precisely because they had been excluded from most definitions of the common good in the past. And one might fairly ask, historiographically speaking, if that’s the end of liberal scholarship. That is, can liberal historians offer anything more than a documentation of one exclusion after another? To put it in even stronger terms, one oppression after another? That is a reasonable question.

The answer is complex, and I won’t endeavor to flesh out all its implications here, since I am already taxing the patience of readers of this blog. But here’s my preliminary answer. Shannon is right that there is a profound dilemma on the liberal left. Much of my book is about that dilemma. Every attempt to seek greater individual freedom and/or social justice becomes ensnared in the market. The market either defines the kinds of “freedom” that are accessible, or activists have to propose vast public interventions in the market in order to secure justice. Many of the activists I write about came to realize precisely that, at least the most self-reflective of them. They came to understand how narrow their choices for creating a different world actually were.

But we err, I think, in assuming that that there are only two options: community or market, tradition or autonomy. The activists I write about succeeded and failed in a dizzying array of ways. What many, many of them sought was simple: a world that was at once free of the intolerable constraints and cruelties of a totalizing “common good” and yet not entirely turned over to absolute market forces. They buried into that dilemma and tried to resolve it. And in doing so most of them did not turn themselves over to a kind of deracinated consumer individualism. Lesbians, for instance, built families and one of the most extensive subcultures in the country. They built a subculture that, as I describe in chapter 6, was imagined as both separate from and committed to a larger idea of a national of global public culture. People of all sorts created new families, rehabilitated old ones, and endeavored to constitute family and community, to reconstitute traditions, and to establish new ways of living. The measure of their success, or at least a critical measure of their success, probably awaits greater historical distance. Shannon is right that they could never entirely step out of market relations – which empowered some, frustrated others, and simply defeated even more. But I find that to be part of the struggle, an essential feature of the history with which they contended.

In fact as I argue in the final several chapters, breadwinner conservatism (or “family values”) was even more powerfully aligned with free-market individualism than the various left-liberal projects of the era. Breadwinner conservatism posited a male-breadwinner family whose moral universe required state protection but whose market chances required no public assistance. For the most radical of conservatives, virtually any public sharing of the costs of market capitalism was an inherent violation of the sanctity of the male-breadwinner family. There are certainly plenty of ways in which the liberalism of the last half century has aligned with the market (which I discuss in the book). But I remain convinced that the collapse of breadwinner liberalism and the rise of breadwinner conservatism was an essential feature of neoliberalism’s recent triumphs – and thus the market’s triumphs – in American public culture.

I’ll finish this belabored point. The American left has over many decades offered basically two related but distinct visions. One is greater personal freedom. The second is social justice. Shannon is correct that both notions have been ensnared in the problem of the liberal subject as it’s been conceived in the West since the Enlightenment. And, thus, in the problem of the market.

This has meant that in an odd way the various collections of ideas on the left – from “free love” to socialism – have bounced around between an extreme personal libertarianism on one side and an extreme statism on the other (much like, in a strikingly different valence, ideas on the right do). In the period covered in All in the Family, this led to two profound dilemmas. The first was what happens when securing individual freedom requires an activist state. The second is what happens when achieving social justice for some requires constraining the liberties of others. These are, of course, long-standing tensions in American political history. But they took on a specific valence and quality in the post-1960s period.

And here’s where Shannon and I might agree more than we imagine. I believe, and argue in the book, that one of the outcomes of the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s was an alignment of middle class notions of “personal freedom” with the market. But, and here’s where we differ, I don’t entirely blame liberals for that. Some of it is their faulty, to be certain. But so many other factors were in play, including the limits of American constitutional law and political opposition, that I don’t see this as an easy parlor game of assigning blame.

Shannon’s second major critique, which he hints at in the review but makes clearer in one of his contributions to the comment string [the one exception to my announcement that I would not be responding to the comment string], is that I adopt a disingenuous historicism that offers an inadequate moral guide to action. His example is the Great Society’s focus on male breadwinners. Shannon argues that I claim that Great Society liberals should have been more responsive to changes in women’s labor patterns – that is, rather than create laws to shape the family life they wished to see (male breadwinner, nuclear families), they should have responded to historical change (i.e., women entering the market in record numbers). He claims, if I understand him correctly, that this position is morally weak because it offers not fixed principles but only a demand that historical actors change with the times. This becomes a sort of sociological teleology – all social change is good.

I agree that such a principle has great moral weaknesses. And to the extent that I endeavor in the book to show the limits of Great Society liberal visions, I am certain that I overemphasize sociology at the expense of moral certainty. If readers come away from the book with the impression that I believe historical actors – especially policymakers and politicians – should never apply moral reasoning to their decisions and should only accept whatever social change is thrown in front of them, then I have certainly failed. However, my intention is rather different. My intention is to show what happens when policymakers endeavor to craft policies that are radically at odds with social reality.

And here I’ll come back to Shannon’s point and defend my own. After seven years of research and a great deal of thinking about this question, alongside debating it in venues such as this, I still remain convinced that Great Society liberals would have been better off crafting policies that recognized and incorporated women’s centrality to market labor and family breadwinning than crafting policies that presumed that only men were breadwinners and only men’s position in the marketplace mattered. If I have insufficiently explained why I think that is the case, a reality I fully accept as a possibility, then I have not lived up to my charge as a historian. And that’s my own failure, and Shannon is right to point it out.

Finally, let me just say that my sense of this period – and I hope the sense that comes through in All in the Family – is more complex than the “Manichean struggle” Shannon accuses me of seeing. The totalizing public culture, and the totalizing “common good,” of breadwinner liberalism was not a timeless tradition. It was the creation of a very specific, and short, period in American history. That it came apart is not surprising. It came apart just as earlier totalizing public cultures and notions of the common good came apart. It came apart just as earlier gender and sexual regimes came apart. Stuff comes apart. I am more surprised historically by things that persist, by things that last. Both the coming apart and the persistence require explanation; they require a narrative that makes them legible to the present. Those narratives ought to be guided by moral reasoning, to be certain. But they also ought to be guided by a healthy skepticism of totalizing cultures and a sensitivity to how and why people come to feel confined by them.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Pingback: Reading: All in the Family at s-usih.dev | Katherine Rye Jewell