(This is the fifth in our film noir series. Thanks to Ben, David, Ray, and Tim for their highly entertaining and insightful posts, and special thanks to Ben for getting USIH involved. See his original post for details on the film noir blogathon and the Film Noir Foundation.)

Unlike my colleagues, I am not dedicating my blogathon contribution to one of the noir classics. Instead, I will analyze the not-so-hidden meanings of a recent film that fits the neo-noir category, among other genres, in the typical postmodern fashion of mixing and mashing: Sin City, the 2005 adaptation of Frank Miller’s neo-noir “Dark Horse Presents” comic series from the early 1990s (itself based loosely on a 1950s graphic novel series). Co-directed by Miller and Robert Rodriguez (with “special guest director” Quentin Tarantino), Sin City gives beautiful, digital form to an ugly urban dystopia (“Basin City”), with an all-star cast that includes Bruce Willis, Mickey Rourke, Clive Owen, Jessica Alba, Brittany Murphy, Benicio del Toro, Rosario Dawson, Josh Hartnett, and Elijah Wood, among others. Watch the trailer for a taste:

The Sin City plot, so far as one exists (among the three self-contained stories within the film), is not really worth summarizing here because it is immaterial to the meaning of the film. What is that meaning? At the most obvious level, the film is about the banality of violence. Shot mostly in black-and-white, which enhances the noir elements of the film, the only color consistently laid over the colorless screen is red. Blood red. There’s a lot of red because there’s a lot of blood. But despite of all the blood, despite all the violence, despite all the torture, there is no remorse. The viewer is not asked to feel bad for the people getting slaughtered. The viewer is not asked to feel anything. We’re meant to let the violence wash over us as we concentrate on the powerful if detached aesthetics of Basin City.

Sin City’s failure to garner an empathetic, much less sympathetic, audience was the crux of a host of ambivalent to negative reviews. Reviewing the film for The New York Times, Manohla Dargis writes disapprovingly:

The soporific vibe isn’t helped by the fact that “Sin City” has the muffled, airless quality of some movies loaded with computer-generated imagery. The film feels as if it takes place under glass, which makes conceptual sense, since the characters don’t bear any resemblance to actual life: they don’t have hearts (or brains), so there’s no reason they should have lungs or air to breathe. At the same time, Mr. Miller and Mr. Rodriguez’s commitment to absolute unreality and the absence of the human factor mean it’s hard to get pulled into the story on any level other than the visceral. When stuff goes blam, you jump like someone who’s landed on a whoopee cushion. But then you just sit there, wrap yourself in the dark and try not to fall asleep.

Acclaimed New York Times film critic A. O. Scott also wrote about Sin City in an essay linking it back (as well as Kung Fu Hustle) to the first film to effectively mix real people with cartoons, Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), which played explicitly on neo noir themes, right down to the 1930s Los Angeles setting. Scott writes:

But even if the technology is neither inherently dangerous nor inherently wonderful, its applications can be worrisome. It is curious that the new techniques are so often used in the service of parody and nostalgia… And the result is often that the old forms, as they are spiffed up and retrofitted, are also emptied out. Mr. Rodriguez, for example, has rendered a gorgeous world of silvery shadows that updates the expressionist cinematography of postwar noir without expressing very much at all. His city, with its tough guys and femmes fatales, feels uninhabited, and the social anxiety and psychological unease of the old film noirs has been digitally broomed away. Instead, “Sin City” offers sensation without feeling, death without grief, sin without guilt and, ultimately, novelty without surprise. Something is missing—something human.

Both Dargis and Scott are correct in the descriptive sense. But they seem to miss the larger point. The brilliance of Sin City—and it is brilliant—lies not in its ability to connect to its audience in some human capacity, but rather, in the ways that it reflects America circa 2005, desensitized to horror by its awful war in Iraq and revelations of torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib—torture sanctioned by the upper rungs of the chain of command. Silja J. A. Talvi overtly makes this link in an article she titles “Torture Fatigue,” where she quotes psychologist Bruce Levine: “When you become disconnected from your own alienation [from society], you become cut off from your humanity… You become numb to all kinds of atrocities.”

I think Levine is onto something with his “disconnected from your own alienation” phrase. As historian David Steigerwald argues, alienation is no longer a concept used to describe our current state. Instead, we’re collectively numb. It’s in this context that we need to situate Sin City. In contrast to mid-century film noir, when cynicism was meant to be felt as something, perhaps as a symptom of alienation, Sin City is utterly devoid of feeling. And rightly so. In his post on The Third Man, Ray poses a bifurcation between noir and liberalism, the former too despairing, the later at least offering a message of redemption, if not a naïve one rooted in a predictably happy ending. Sin City does not work along these lines. It represents a void, plain and simple.

Or take Tim’s contextual analysis of Touch of Evil. Tim writes:

I think something of the significance of film noir, at least in the 1950s, is in the way that the genre captures that slice of the repressed dissatisfaction, always roiling below the surface, of the decade. If the period’s intense anti-communism resulted in idealist visions of America (i.e. as the proverbial “city on the hill”), then noir captures that city’s messy undercurrents. The aesthetic beauty in those films alerts us to their artistry, but their mood reflects what every close-up of the decade reveals: flaws, cracks, and imperfections in the foundational narrative.

In contrast, Sin City is not a return of the repressed in this sense. Everything is out in the open, nothing bubbles out from under the surface, because there is nothing. Just violence. And beauty.

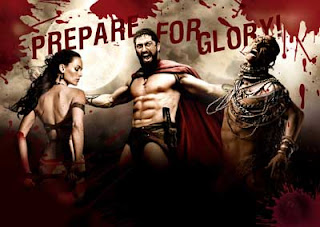

Nihilism wrapped in aesthetics is, of course, one of the historical characteristics of fascism. Another recent Frank Miller adaptation, 300, a fictional account of Spartan resistance to the Persian Empire, has in fact been charged with expressing militaristic values approaching fascism. In his typically amusing yet overstated way, Slavoj Žižek argues against this liberal consensus grain. In an essay titled “The True Hollywood Left,” Žižek relates the Persian Army—multicultural, hedonist, with the latest in long-range weaponry—to U.S. imperialism. Conversely, he relates the disciplined Spartans to the resistance to American imperialism and advises the left to quit distrusting discipline as a means to an end.

But what makes Žižek’s essay on 300 more interesting, and relevant to a discussion of Sin City, is his political analysis of the film’s form. 300, like Sin City, is highly stylized digital unreality. Žižek writes:

What makes 300 notable is that, in it (not for the first time, of course, but in a way which is artistically much more interesting than, say, that of Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy), a technically more developed art (digitalized cinema) refers to a less developed one (comics). The effect produced is that of “true reality” losing its innocence, appearing as part of a closed artificial universe, which is a perfect figuration of our socio-ideological predicament. Those critics who claimed that the “synthesis” of the two arts in 300 is a failed one are thus wrong for the very reason of being right: of course the “synthesis” fails, of course the universe we see on the careen is traversed by a profound antagonism and inconsistency, but it is this very antagonism which is an indication of truth.

Žižek’s conclusion is cryptic at best. But what I take him to mean is that westerners witness horror via the mediated unreality of modern, digital technologies. We don’t feel horror. Only our victims do. This is the “profound antagonism” of Sin City. This is the aesthetics of post-alienation.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andrew,

I wish I could speak specifically to the movies that are the topic of this post—meaning *300* too. But I haven’t seen either. Given my ignorance, I can at least converse on the meta-issues at hand.

I sympathize with what you propose about neo-noir, the genre that resurfaced in the 1970s going forward, and its larger symbolism. I’m depressed/impressed by what the films tell us about our numbness to even alienation. If that’s not the postmodern condition, I don’t know what is.

But I wonder if the “deafness” metaphor isn’t more capacious. By this I mean that, from the 1970s onward, pockets of society have developed an ability to be deaf—lacking in empathy, ignorant of (purposeful), exhibiting an inability to hear (or see) violence in all its forms. This is radical individualism at its extreme—something beyond alienation, and indicative of our occasionally intense cultural and social fragmentation. I don’t think it’s nihilism, however, since individuals retain their beliefs, even exhibiting and acting on those beliefs fervently at times. Furthermore, this deafness, or extreme alienation, feeds or creates what Hofstadter called the “paranoid mind.” The paranoia, however, is merely a symptom of the postmodern condition—its malaise and numb deafness.

It seems that Livingston’s most recent book did a fine job of discussing this aspect of our postmodern condition.

What’s scary to me about this symbolism, thinking as an amateur sociologist, are the implications for the solution. Small-time violence and remote wars appear unlikely to shake American society out of the deaf malaise. I fear that only widespread disruptions, or violence, to everyday life will provoke us out of the deafness and into a more acute awareness of consequences of ignoring civic duties.

I digress. But like you, I’m trying to understand something of the overall direction of the last 30-40 years without being teleological.

– TL

A very interesting post that raises a subject about which I want to hear more. Andrew you contend:

“The brilliance of Sin City—and it is brilliant—lies not in its ability to connect to its audience in some human capacity, but rather, in the ways that it reflects America circa 2005, desensitized to horror by its awful war in Iraq and revelations of torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib—torture sanctioned by the upper rungs of the chain of command.”

Okay, how do we gauge sensitivity to the culture and events around us? I ask this out of frustrated curiosity because while I can agree up to a point with your characterization I wonder what the other side looks like. Were Americans more sensitive during the Civil Rights era or World War II or the Civil War? Is the French Revolution the standard for being outraged and then reacting.

We don’t feel horror–true enough. How should we feel it? Do we turn to an army of citizens–all citizens–again? Do we trust the many Americans who have been involved in witnessing atrocities around the world–some perpetrated by the US itself–as real enough?

You have raised points that are fundamental to a reflective culture but what would that culture look like?

Ray,

I suppose, as historians (or reporters), we look for resonance to gauge sensitivity (or insensitivity). We look for themes we see to resurface in other motifs, whether they are other films, newspapers, signs, oral histories, etc.

As for comparing today’s numbness or deafness or alienation to other historical events, perhaps resonance and duplication in other forms are again the answer.

As for standards, I suppose counting works—relative to population estimates? So if X number of bodies come out of X population for the issue at hand, we can judge something of that culture’s sensitivity.

One of the questions I’ll probably end up posing for Cotkin in my review of *Morality’s Muddy Waters* is how we gauge sensitivity to moral complexity beyond the historical figures directly involved. In other words, doesn’t the popular reception to atrocities and injustice count something toward a nation’s ability to empathize?

As for the question about “what would that culture look like?,” I think, again, we’d see widespread artifacts of dismay–newspapers, blogs, tweets, letters, oral accounts, demonstrations, etc.

– Tim

Tim and Ray: Thanks for your challenging comments and questions. I confess that I have no easy answers. I was being intentionally provocative, I admit, by putting Sin City in the context of Abu Ghraib and what I felt to be a lack of collective disgust over torture done in our names. This is not to say that people weren’t disgusted–plenty were. But the meta- or mainstream culture did not respond as such, it seems to me, which is why Sin CIty seems like it speaks to that moment.

Perhaps Friday traffic is light, but I was expecting people challenge me on this post for ignoring gender. The gender aesthetics or politics of Sin City and 300 are pretty reactionary. To the degree that some people surely were unable to disassociate that from other redeeming features. In Sin City, the fact that all of the women seemed like postmodern Betty Boops was another aspect of the washing-over effect (like the violence). Also, it was in keeping with the 1950s graphic novel aesthetic.

Sorry to be late to this party. This is a terrific post, Andrew. But, like Tim, I haven’t seen either Sin City or 300. The general point you make about cultural numbness, however, rings true to me. I’m going to return to our current neo-noir moment in my final blogathon post tomorrow (Monday), which will touch on some of the things you’ve raised here.

Thanks, Ben! I look forward to reading your thoughts on neo-noir. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the whole series, and learned tons. Now I wish I had time to watch some of these old films. With a two-year old and a one-month-old, my chances of viewing them anytime soon are slim. Someday!