Today we have Part II of Matthew D. Linton‘s exploration of the intellectual history of country music (Part I here). Matt draws together old and new, demonstrating lines of continuity between some of the first commercially successful women in the genre with some of the independent voices of today. Enjoy!

In 1952, Hank Thompson released the hit single “The Wild Side of Life.” It told the story of a young woman who chooses the “gay night life” and “places where wine and liquor flow” instead of settling down and marrying the “only one that ever loved you.” “I didn’t know God made honky-tonk angels,” he crooned, “I might have known that you’d never make a wife.” Like the fallen women in Johnny Cash’s “Cry, Cry, Cry” and Ernest Tubb’s “You Nearly Lose Your Mind,” Thompson’s naïve lover is lured from her natural and safe place in the home for the bright lights of town, presumably to intoxication and promiscuity (“you wait to be anybody’s baby” Thompson sings). Country music’s leading men expressed a deep anxiety about the changing role of women, particularly as they had more autonomy outside the home. By 1950, a wife leaving the home and potential cuckoldry were so intertwined that “stepping out” was a synonym for infidelity.

In 1952, Hank Thompson released the hit single “The Wild Side of Life.” It told the story of a young woman who chooses the “gay night life” and “places where wine and liquor flow” instead of settling down and marrying the “only one that ever loved you.” “I didn’t know God made honky-tonk angels,” he crooned, “I might have known that you’d never make a wife.” Like the fallen women in Johnny Cash’s “Cry, Cry, Cry” and Ernest Tubb’s “You Nearly Lose Your Mind,” Thompson’s naïve lover is lured from her natural and safe place in the home for the bright lights of town, presumably to intoxication and promiscuity (“you wait to be anybody’s baby” Thompson sings). Country music’s leading men expressed a deep anxiety about the changing role of women, particularly as they had more autonomy outside the home. By 1950, a wife leaving the home and potential cuckoldry were so intertwined that “stepping out” was a synonym for infidelity.

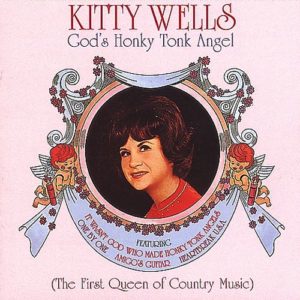

“The Wild Side of Life” was a massive hit for Thompson, spending fifteen weeks at the top of the Billboard country music chart and launching a successful career. More important than the single’s content or even its success was the response it drew from a young unknown musician named Kitty Wells. That same year she recorded a response, “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels” (1952), lambasting Thompson and other male country musicians for solely blaming women for the honky-tonk’s culture of loose morals. Written from the perspective of Thompson’s fallen “honky-tonk angel” and imitating the sound of “The Wild Side of Life,” Wells recounts a tale of a moral (read: good Christian) woman lured to sin by lustful men. As she sings in the chorus, “Too many times/married men think they’re still single/that has caused many a good girl to go wrong.” Thompson was correct, God didn’t create honky-tonk angels, they were created by men who had unmoored sex from marriage, desire from commitment.

Wells’ song sparked a revolution in country music. Despite being banned on many radio stations for its provocative message, it went to number one on the Billboard country music chart making Wells the first solo female musician to accomplish the feat and even crossed over to the pop charts. It made Wells a star and she released a series of chart topping singles between 1952 and 1970, blurring the lines between country and pop music. Her success encouraged Nashville record companies to sign solo female performers and allow them to record songs about women’s experiences.[1] Women were not only the subjects of country songs, but, by the early 1960s, some of its best-selling and critically acclaimed creators.

Wells was also the first artist to tackle, however obliquely, the topic of women’s liberation. In “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels,” she’s explicit that it’s unfair that “all the blame is on us women” and that at the end of most failed relationships “there always was a man to blame.” Still, Wells’ feminism is conservative. Like Thompson, she wants to maintain the existing social order, calling on men to uphold their obligations as husbands. For much of the rest of her long career, Wells played the role of the good wife: defender of hearth and home, vociferous critic of cheating husbands, and protector of the institution of marriage. Only by demonizing the honky-tonk angel could she assert the moral superiority of the good wife, in the process reifying the binary between the chaste wife bound to the home and the promiscuous, homeless fallen woman, drinker of whisky and barroom denizen.

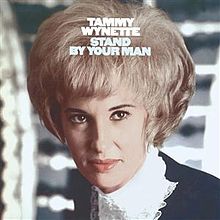

While Loretta Lynn is often viewed as Wells’ heir, her closest lyrical progeny is Tammy Wynette, who brought Wells’ conception of the good wife into the morally fraught late 1960s and 1970s. Her first hit single, “Apartment #9” (1966), was a quintessential (one might say clichéd) story of young heartbreak, but it was not until her marriage to fellow country music star George Jones in 1969, and the public nature of their relationship, that Wynette became a feminist voice. Like Wells, Wynette’s feminism was conservative – it emphasized obligation and looked askance at liberation. If Wells’ good wife chastised husbands for stepping out on their wives, Wynette’s fought a multi-front war to preserve family in the face of dislocating modernity. As the trials and tribulations of her own marriage to the drunken, abusive Jones titillated tabloid audiences, Wynette had a string of hits – “I Don’t Wanna Play House” “D-I-V-O-R-C-E” (1968), and, particularly, “Stand by Your Man” (1968) – documenting the difficulties of keeping family together.[2]

Wynette stressed the sanctity of the female sphere of hearth and home, as well as the institution of marriage and the role of motherhood, even at the cost of her own happiness. In “Stand by Your Man,” she recognizes that “it’s hard to be a woman” because “You’ll have bad times/and he’ll have good times.” Wynette’s good wife and mother is the stoic foundation of family stability. She bears the sorrows, while her husband reaps the fruits of their success. In “D-I-V-O-R-C-E” she protects her young son from a crumbling marriage by spelling out the word making it incomprehensible to the boy. Wynette’s female protagonists are often walked over by their husbands or submissive to their desires (as in the humorous “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad” (1967)). The women in Wynette’s songs are not simple victims, however, they are saints and martyrs

Wynette stressed the sanctity of the female sphere of hearth and home, as well as the institution of marriage and the role of motherhood, even at the cost of her own happiness. In “Stand by Your Man,” she recognizes that “it’s hard to be a woman” because “You’ll have bad times/and he’ll have good times.” Wynette’s good wife and mother is the stoic foundation of family stability. She bears the sorrows, while her husband reaps the fruits of their success. In “D-I-V-O-R-C-E” she protects her young son from a crumbling marriage by spelling out the word making it incomprehensible to the boy. Wynette’s female protagonists are often walked over by their husbands or submissive to their desires (as in the humorous “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad” (1967)). The women in Wynette’s songs are not simple victims, however, they are saints and martyrs

Unlike her contemporary, Loretta Lynn, Wynette’s name became synonymous with country music patriarchy. Though Wynette tried to rebrand after her divorce from Jones in 1976, her album “Til I Can Make It on My Own” (1977) finds her asserting her independence as an artist, she was never able to shed her identity as Jones’ wife and duet partner. In 1980 she relented recording another album of duets with Jones as both artists saw a steep decline in sales after their breakup. In 1990, Wynette was again catapulted into the national spotlight when first lady in waiting Hillary Clinton said “she wasn’t some little woman standing by her man like Tammy Wynette” in a 60 Minutes

interview about her husband Bill’s alleged affair with Gennifer Flowers when he was governor of Arkansas. Wynette disputed Clinton’s interpretation, but the damage was done. Ironically, Wynette passed away in April 1998 in the midst of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, a period when Hillary Clinton came to symbolize the ‘stand by your man’ attitude she condemned in Wynette’s single.

Contemporary female country musicians have sought to overturn the prior generation’s hearth and home feminism, stressing freedom and equality. The Dixie Chick’s emphasized freedom on their hit single “Wide Open Spaces” (1998).[3] Shania Twain had a massive pop hits with the feminist anthems “Man! I Feel Like a Woman” (1997) and “That Don’t Impress Me Much” (1997) the former of which featured a cheeky spoof of Robert Palmer’s iconic “Addicted to Love” music video with a leather-clad Shania rocking in front of a band of vacant, bare-chested male models. Pop country stalwarts Kacey Musgraves and Maddie and Tae have protested their bro-country brethren’s dismissive attitude toward women as voiceless sex objects in their singles, “Good Ol’ Boys Club” (2015) and “Girl in a Country Song” (2015).

No one has more overtly overturned country’s narrative of female confinement than Nikki Lane, however. Building on Well’s initial challenge to the patriarchal Nashville establishment, Lane has built an identity as a feminist country musician by rehabilitating its most marginal character: the honky-tonk angel. Born in South Carolina, Lane began her career as a fashion designer in Los Angeles and New York before moving to Nashville to focus on music. Her first album, “Walk of Shame” (2011), was a fusion of country and rock in the outlaw tradition. The title track finds the honk-tonk angel waking up from another one-night stand in a stranger’s bed. Notably absent from the song is a core component of its title: shame. Lane’s honky-tonk angel has done this before and will do it again and doesn’t care much about what “Mack on the corner” thinks as she walks by.

Lane built on the themes from her debut album in her 2014 breakout, “All or Nothing.” Produced by The Black Key’s Dan Auerbach, it doubles down on Lane’s debut country-rock sound and lyrics of female liberation. “Man Up” finds a fed up housewife challenging her dead-beat husband to get a job and show some initiative, threatening to leave, and having affairs behind his back. It wielded the threat of cuckoldry that animated Hank Thompson’s release as a weapon. For Lane, if the loser husband ignored his wife, she had every right to step out on him. The album’s apotheosis, “Sleep With a Stranger,” is the distillation of Lane’s liberated, care free honky-tonk angel. “I ain’t looking for love/just a little danger/ tonight would be a good night to sleep with a stranger,” she sings in the first verse. The sexually liberated honky-tonk angel doesn’t have to suffer through Wynette’s abusive confinement, she can have her pick of the “cowboy like a lone ranger” or the “motorcycle bandit.” In many ways Lane’s “Sleep with a Stranger” is the inverse of Wynette’s “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad.” Lane’s honky-tonk angel controls her own desires, while Wynette’s good wife tries to “learn to like the taste of whisky” to fulfill her husband’s fantasies.

Lane’s most recent album, “Highway Queen” (2017), expands Lane’s liberating vision outside the bedroom. If her first two albums largely limited explorations of liberation to sexual freedom, “Highway Queen” sees Lane transforming the honky-tonk angel – defined by her sexuality and largely confined to the seedy barroom – into the highway queen – a wholly liberated woman confined by neither local patriarchy nor small town claustrophobia. This persona is in line with Lane’s, as she has grown as an entrepreneur into merchandising, modeling, and retail. The title track reminds listeners that “Some folks say that she’ll settle down in some old town/ but as best you know this long, long road she ain’t gonna come around.” There is love and heartbreak on this album, it’s less emotionally guarded than previous releases. Her husband Jonathan Tyler, a solo artist with a sound similar to Jack White, is in her band and they duet on several tracks. In juxtaposition to Wynette who was defined by her marriage and collaboration with Jones, however, Lane is unrivaled on the record and on stage. While Wynette was doomed by critics and fans to stand by her man as an embodiment of the good wife, Lane’s honky-tonk angel turned highway queen reminds listeners that she’s her own person. As she sings in one of her newest songs, “The highway queen don’t need no king” to hold her down or define her.

Lane’s most recent album, “Highway Queen” (2017), expands Lane’s liberating vision outside the bedroom. If her first two albums largely limited explorations of liberation to sexual freedom, “Highway Queen” sees Lane transforming the honky-tonk angel – defined by her sexuality and largely confined to the seedy barroom – into the highway queen – a wholly liberated woman confined by neither local patriarchy nor small town claustrophobia. This persona is in line with Lane’s, as she has grown as an entrepreneur into merchandising, modeling, and retail. The title track reminds listeners that “Some folks say that she’ll settle down in some old town/ but as best you know this long, long road she ain’t gonna come around.” There is love and heartbreak on this album, it’s less emotionally guarded than previous releases. Her husband Jonathan Tyler, a solo artist with a sound similar to Jack White, is in her band and they duet on several tracks. In juxtaposition to Wynette who was defined by her marriage and collaboration with Jones, however, Lane is unrivaled on the record and on stage. While Wynette was doomed by critics and fans to stand by her man as an embodiment of the good wife, Lane’s honky-tonk angel turned highway queen reminds listeners that she’s her own person. As she sings in one of her newest songs, “The highway queen don’t need no king” to hold her down or define her.

[1] It would be wrong to say there were no female country musicians before Kitty Wells, Patsy Montana and the Carter sisters had success in the 1930s and 1940s. Wells was a pioneer in singing from a women’s perspective about women’s issues.

[2] George Jones resented Wynette’s willingness to air publicly their marital acrimony. Jones shot back in 1974 with “The Grand Tour,” which told the story of Jones’ home fallen into decrepitude after a wife (presumably Wynette) leaves with their young child. Jones was not only criticizing Wynette’s duplicity – appearing as a good wife standing by her man even as she plans her exit – but also the media who had pried into Jones and Wynette’s private life. Wynette fired back with “The World’s Most Broken Heart” (1976), which imitated the sound and subject-matter of “The Grand Tour,” but stressed the primacy of a woman’s suffering over a man’s when a marriage ends.

[3] The Dixie Chick’s most important contribution to country feminism was in flipping one of the ugliest country traditions: the murder ballad. A staple of traditional country and revived by the 1970s outlaw country movement, murder ballads’ told stories of men killing women, sometimes with remorse (“Delia’s Gone”), but often without (Cash’s “Cocaine Blues”). “Goodbye Earl” (1999) flipped the script. It featured two female friends teaming up to poison an abusive husband. It reached number eight on the Billboard pop charts, though the Nashville establishment was none too happy about its content and it was barred on some country radio stations. The Dixie Chick’s baton has been picked up by bands like Hurray for the Riff Raff, which have continued to push back against the murder ballad tradition.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Note to self: buy Nikki Lane’s albums.

Note to Matt: Thanks for this fantastic post and series!

OMG Matt, how awesome that such good blog posts also provide wonderful music discoveries! Hells yeah.

On Wynette — I enjoyed “Stand By Your Man” in high school and college but only due to the melody — so I would satirically replace the lyric/s coming after “Stand by your man –” with “even if he’s cold, and beats you.” Sad to find out I was closer to the mark than I realized.

Are you going to address Miranda Lambert? She sort of distills or mainstreams artists like Nikki Lane with a song like “Vice” on her latest album. (Of course, she has made plenty of hay on kicking the asses of cheating partners–when Carrie Underwood tried that my heart sank. Jeez.) Still, Vice; It’s a wondrous play of influences. From the signifier of the record pops and scratches on the song (“old” in the sense of archiving the cuckolded male country partner: read Blake Shelton) and then only mildly apologetic about stepping out (I shouldn’t do it again, but shit, desire is what it is fella ). In other words, I’m interested about where you think the Nikki Lanes and Wynettes meet in the tumble where the mainstream industry in an artist like Lambert meet up with acts that are less concerned with the same kind of broad listenership. This was the ground that the Dixie Chick mined to great effect by covering Patti Griffin or the like. The industry pulls from that kind of stuff in interesting ways. Another really great, fun post.

Hi Peter,

Sorry for the slow response, but I’ve been mulling your thoughtful comment over. I’ll admit at the outset that I’m not a huge Miranda Lambert fan (she’s my least favorite of the Pistol Annies). I read her 2016 album, The Weight of These Wings, as an attempt to bridge the pop and indie country universes. She’s friendly with many of the genre’s heavy hitters (Angaleena Presley, Ashley Monroe, and Natalie Hemby, who co-wrote many of her new songs) and has promoted several up-and-comers from the indie scene. Her latest work reminds me of the tightrope walked by Kacy Musgraves. Both are trying to appeal to a broad pop sensibility – country and otherwise – but want to keep the Nashville establishment at arm’s length. Musgraves has been open about her skepticism toward Nashville: she disagrees with its politics and finds the scene suffocating. Lambert’s reasons may be more complicated. I don’t know how divorcing Shelton has shaped her reception in Nashville. She is also pulling a classic country move a la Willie Nelson: Texan has a bad time in Nashville and pivots their sound to find a different audience.

I think Lambert differs from Lane in degree rather than kind. She still refers to her infidelity and drinking as a vice, even if she does it with a wink. Lane doesn’t wink, she glories in the highway queen character as symbol of freedom and rejection of “respectable” gender roles. These choices are driven by personality, but also by intended audience. Lane is a rock musician who has gradually turned country. Her core audience is a rock audience – under the guise of the nebulous “Americana” label. Lambert is a country musician/pop star trying to stretch that tradition. She isn’t courting rock audiences – she would have hired producer Dave Cobb (who she worked with on the great 2016 American Family record) if she wanted to do that. Ultimately, she will succeed or fail (at least in current form) depending on if her transformation is embraced by country music audiences. All indications are that she has succeeded at finding critical and commercial acclaim so far. I’ll be curious to see if her next album will pivot back to her pop roots (with this as a kind of breakup record) or if she will push further into Americana or rock territory.