Editor's Note

The following is a guest post by Jacob Hiserman, a second-year M.A. student in History at Baylor University. Jacob’s scholarly interests are antebellum intellectual history, higher education, Christian benevolence, and Southern history. He also enjoys reading Romantic and modern poetry and P.G. Wodehouse’s stories.

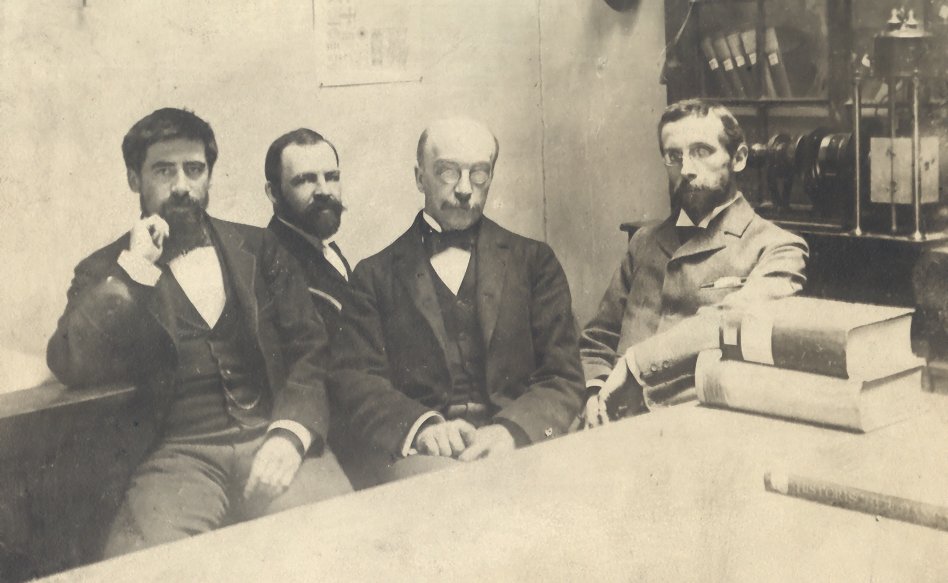

James Harvey Robinson, second from right, and other UPenn History Faculty, 1892 (University of Pennsylvania, University Archives & Records Center, History Club of Philadelphia Records, 1894-1899.)

“I have been a stranger in a strange land.” (Exodus 2:22, KJV). That was one of my sentiments when I finished my first post at this blog that explored twentieth-century intellectual history and the meaning of America in Robert Skotheim’s American Intellectual Histories and Historians (Princeton, 1966). As an antebellum U.S. intellectual historian, I had journeyed “far from the home I love” (as Hodel in Fiddler on the Roof would have it) but the new home I found would not let me leave so quickly.

In American Intellectual Histories and Historians, Skotheim maintained totalitarianism’s threat united Progressive historians and their reactionary brethren to double-down on what it meant to be American: a “re-embracement” (as he called it) of some quintessential American values and “common-sense.” Now, notice the order of subjects in the title. Histories come first and those who write them follow. It is the authors behind the histories I trace in this blog post. The Progressive historians loomed large for Skotheim as they commanded two out of five chapters in American Intellectual Histories. What fascinated me in my first read was that Skotheim, a higher education administrator, carefully noted the collegiate backgrounds of most of the historians he surveyed. As a historian of higher education, such details scream at me. All the colleges the Progressive historians attended for their undergraduate degrees (or at least part of them) were in the Midwestern United States. It seemed significant and merited an investigation. What I found raised questions about the roots of modern intellectual history and kept me in the twentieth-century home for another post.

Skotheim dove into the collegiate and regional roots of the “early chroniclers” or pre-Progressives (because they shared some intellectual traits and regional roots with the Progressives) and the Progressives. Moses Coit Tyler (1835-1900), an Episcopalian minister and son of a Congregationalist minister, was raised in the Midwest and was a professor of English literature at the University of Michigan, a Midwestern institution of higher learning. Skotheim highlighted a few of Tyler’s works of American intellectual history including The Literary History of the American Revolution, 1763-1785. Opposite the religiously-motivated Tyler stood the avowed “secularist” Edward Eggleston (1837-1902). Skotheim wrote of him:

“Born and raised in Indiana, he was a Methodist preacher throughout his twenties, a writer for Christian denominational publications as well as other periodicals during his thirties, and as late as his forties, he returned to a pastorate.”[i]

Eggleston’s drift away from religion came through his recognition that evolution did not square with Methodism dogma. Nonetheless, his Midwest origins and strong denominational involvement are significant. On the Progressive spectrum of historians, James Harvey Robinson (1863-1936), the New Intellectual History scion, was born in the Midwest. Charles Beard (1874-1948) attended DePauw College in Indiana founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1837. Furthermore, Carl Becker (1873-1945) hailed from Waterloo, Iowa and pursued studies at Cornell College—a school run by the United Methodist Church—for one year but spent the remaining three at the University of Wisconsin. Additionally, Vernon Louis Parrington (1871-1929) lived in the Midwest in his early years and went to the College of Emporia, a Presbyterian institution of higher learning established in 1882. Finally, Skotheim mentioned Merle Curti (1897-1996) had a Nebraska upbringing but all his academic degrees from Harvard. The pattern of a Midwestern undergraduate degree paired with an Eastern Ivy league graduate degree held true for most of the Progressive historians Skotheim examined. Reading Skotheim gives one a sense of the magnitude of Midwestern intellectuals in twentieth-century American life and culture.

Very recent historical scholarship confirms such an assertion. In 2011, Kenneth H. Wheeler wrote in his history of Midwestern colleges, Cultivating Regionalism: Higher Education and the Making of the American Midwest that Progressive leaders largely came from the Midwest and its denominational colleges. Wheeler’s book is a masterful view of the vast impact Midwestern collegiate institutions made upon American intellectual life. He argued the height of Midwestern culture came in the Progressive Era (1890-1920) and that Midwestern colleges facilitated the sciences the Progressives reverenced. Furthermore, Wheeler asserts the two pillars of antebellum Midwestern college education were the construction of social harmony and education and uplift of the poorer classes. Skotheim touched on these themes in American Intellectual Histories because he called “reform sympathy”—a vision that included social unity and poverty relief—a major, unifying thread of Progressive intellectual historians. More recently, Jon Lauck and Jess Gilbert examined Progressive intellectuals in different lights. Lauck’s From Warm Center to Ragged Edge: The Erosion of Midwestern Literary and Historical Regionalism, 1920-1960 (featured in two recent posts at this blog) recovers the lost field of early twentieth century Midwestern history. In a similar vein, Jess Gilbert’s 2015 monograph, Planning Democracy: Agrarian Intellectuals and the Intended New Deal, chronicles the Progressive vision of democracy that stemmed from Midwestern intellectuals in the USDA’s land-use program. Both works highlight the importance of Midwestern intellectuals and Midwestern history to the social forces of the early twentieth century. On the other hand, Skotheim’s book provides us with a dissimilar window into intellectual history: how the Midwest influenced American intellectual history through Progressive ideology.

How does Skotheim’s American Intellectual Histories draw that out? I avow it magnifies the Midwest’s importance in American intellectual history but gives more questions than answers. One query I had after reading Skotheim, Wheeler, Lauck, and Gilbert is whether the Progressive intellectual historians Skotheim writes of alter the dynamic tension between region and nation. Wheeler and Lauck explicitly acknowledge that tension. Wheeler writes: “Regionalism is precisely the dialectic between thought and action, between the imagined and the tangible.”[ii] Moreover, Lauck attests the likes of Frederick Jackson Turner, Josiah Royce, and Hamlin Garland were partisans for a robust Midwestern field of inquiry separate but related to study of the Midwest in the American nation.[iii] For Gilbert, the relationship of what is distinctly Midwestern stands in strong relation to what is national because participatory democracy connects national and regional levels. In Skotheim’s work, the Progressive intellectual historians rarely delve into what is regional about America. Their books continually concerned “American civilization” or civilization-in-general.[iv] Additionally, the Progressive intellectual historians in Skotheim’s narrative and their opponents had what I call a “Puritan hinge” around which their monographs and scholarship turned. Each side used the Puritans to advance their interpretation of American intellectual history. For late nineteenth and twentieth century American intellectual history, the Puritans were “good to think” with (in the Darntonian sense). Yet, where do the Progressives’ Midwestern roots show through?

I close with one final question. The Progressive intellectual historians in Skotheim’s work might have been influenced by their region more than I’ve seen in the surface-level analysis above. Skotheim emphasized their concern with an “environmental” interpretation of intellectual history that did not posit free-floating ideas but grounded those ideas in social and cultural trends. This heritage profoundly shaped intellectual history as we know it today. Did this Progressive “environmental” focus stem from the importance of the Midwestern environment (or region) in their own intellects and writings to form the basis for their theory of intellectual history? I look forward to pondering those questions with this community of intellectual historians and gradually revoking my status of “stranger” and wanderer amidst twentieth-century intellectual history.

____________________

[i] Robert Allen Skotheim, American Intellectual Histories and Historians (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966), 49-50.

[ii] Kenneth H. Wheeler, Cultivating Regionalism: Higher Education and the Making of the American Midwest (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2011), 103.

[iii] John Lauck, From Warm Center to Ragged Edge: The Erosion of Midwestern Literary and Historical Regionalism, 1920-1965 (Iowa City, IO: University of Iowa Press, 2017).

[iv] For example, James Robinson’s Introduction to the History of Western Europe (1903); Charles Beard’s The Rise of American Civilization (1927) and The American Spirit: A Study of the Idea of Civilization in the United States (1942, fourth part of “The Rise of American Civilization” series); Carl Becker, The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas (1922); Vernon Louis Parrington, Main Currents in American Thought: An Interpretation of American Literature (1927-1930); and Merle Curti, The Growth of American Thought (1943).

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

David S. Brown’s Beyond the Frontier: the Midwestern Voice in American Historical Writing is another book that considers these issues.

Jacob,

You raise some really great questions, and I am so glad you are writing on these issues!

As you note, the tension between region and nation is one of the most important–and most elusive–of these issues. Lauck and Gilbert (and Brown to a slightly lesser extent) emphasize a regional rivalry with New England or with the urban East. In essence, both groups of intellectuals were trying to claim the ground of “national culture” for their home region while consigning the other to being merely a regional culture.

This has been a fairly longstanding interpretation: to a certain extent, Lauck reading back into the historical record the grumblings of a number of mid-century Eastern intellectuals (like Hofstadter) who were annoyed about Midwestern cultural hegemony. (Another crucial informant for this interpretation is Warren Susman, who took his doctorate at UW-Madison, but had some divided regional loyalties. Paul Murphy’s wonderful new article is a great source for finding out more about Susman.) In some ways, this interpretation even goes back to Turner himself.

Interregional rivalry is certainly a useful paradigm and it has some undeniable validity, but it can also overwhelm other readings which I think you’re gesturing at in noting the importance of religious or sectarian throughlines or divisions. Certainly, within the Midwest, there are a number of different religious traditions which have given rise to very different subcultures, some of which are anchored historically or imaginatively in other regions–as with the Puritans and New England. So I think there are important things to be said for cross-regional linkages as well as inter-regional rivalries: the Midwest isn’t a bloc, as I have to remind myself often!

Andy, thanks for your comment. I’m grateful for your succinct summary of two major interpretive frameworks in Midwestern historiography. It is a new field for me and I’m eager to learn more about it. It has become clear to me in writing this post and writing my thesis (in which I devote a chapter to the antebellum American Home Missionary Society and its ideas of benevolence and gender in the West) that one of the great ironies of American history is the fact that the East ( the South included in that categorization) in some ways undermined its cultural hegemony in its evangelization and settlement of the West and Midwest.

Speaking of evangelization, could you speak to whether or not contemporary religious history of the Midwest is challenging the interregional rivalry paradigm? Any books you’d recommend on that topic?

Jacob: I don’t have much in the way of substance to add to this discussion. But I do want to say thanks(!) for taking the time to submit a guest post. I love being reminded of the concerns, ideas, tensions, and biographies of the Progressive Historians. James Harvey Robinson has loomed as an important figure in my work. And I recently completed a review of Hoeveler’s new book on Bascom and the Wisconsin Idea. Thanks, Tim

Tim: You’re welcome and I’m glad I played a part in keeping an important topic in your intellectual purview through this post. That is one of the beauties of an intellectual community. Where will your review appear (or where has it appeared)? I’d like to read it.